|

|

|

|

|

|

How To Get More Of It

Looking through Post-MFA prism

Abdur Razzaque

The expiry of the Multi-Fibre Arrangement (MFA) regime has brought a great deal of uncertainty about Bangladesh's future export earnings and sustainability of macro balances with potential adverse consequences on economic growth. Taking advantage of the MFA quota system, Bangladesh demonstrated a spectacular export performance, with exports of readymade garments (RMG) rocketing from just $10 million in FY 1985 to about $6,400 million in FY 2004-05. In the mid-1980s, only about 0.1 million people were employed in the RMG industry, but over the next 20 years it grew rapidly to reach 1.9 million (or, 35 percent of all manufacturing employment in the country) 80 percent of whom being women.

There is some suggestion that if jobs created in the complementary enterprises as a result of the growth in this sector are considered, the number of people either directly or indirectly depending for their employment on the existence and expansion of the RMG sector will rise to three millions. The growth of RMG exports has had favourable effects on macroeconomic balances. The trade deficit has declined from around 10 percent of GDP in the early-1980s to around 5.5 percent in 2004. The rising share of export trade in the economy brightly contrasts with the declining significance of foreign aid, which now constitutes only about 3 percent of GDP down from 7 percent of the mid-1980s. It is in this context that the RMG-led export growth is thought to have transformed the country from a predominantly aid-dependent country to a largely trade-dependent nation. Being a labour intensive sector coupled with provider of employment mostly to women, the RMG sector has had a strong influence on poverty alleviation and human development in Bangladesh.

The abolition of MFA quotas has exposed Bangladesh to fierce competition from a large number of countries whose exports have so far been severely constrained by quantitative restrictions imposed by developed countries. During the first six months into the post-MFA period, for which data and information are available, Bangladesh has somewhat managed to maintain a modest growth of its RMG exports, largely due to a robust performance of knitwear exports. Notwithstanding this, it may still be too early to predict anything about the country's future export prospect. China, the main threat in the global quota-free apparel market, continues to face export restrictions in the EU and the US. A particular clause embodied in the Protocol of China's accession to the WTO enables the US to restrict imports of textile and clothing products from the former until 2008 and fearing that many other countries (like the EU) could take advantage of this precedent, importers in important markets might not want to rely wholly on China for procurement immediately after the MFA-phase out. However, from 2008, when keeping restrictions on China will be difficult as per the WTO rules, only then the real competitive pressure in the market will be realized. It needs to be mentioned here that most academic empirical studies predicted adverse consequences of MFA phase-out on Bangladesh and convincing arguments to defy those predictions have not yet been found.

The post-MFA period has coincided with Bangladesh's reinvigorated policy efforts in reducing poverty, as reflected in the preparation of its Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (PRSP). Although critics regard the poverty reduction strategy as a donor driven initiative without any apparently significant policy shift that would make a difference in the PRSP regime, the attainment of Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) is expected through the implementation of the PRSP. The first target under the MDGs is to halve the number of people living in poverty (from the level of 1990) by 2015. In recent times, Bangladesh has made some progress in reducing poverty. Along with an annual average GDP growth of 5 percent over the decade of the 1990s, the proportion of people living below the poverty line declined from 59 percent in 1991-92 to 50 percent in 2000. That is, on average poverty fell by one percentage point per annum. This apparently impressive performance is overshadowed by a frustrating fact that despite the fall in the proportion of people living below the poverty line, the absolute number of poor people actually remained virtually unchanged, at about 63 million.

For any low-income developing country, the best way (and most

Feverish competitiveness

often the only feasible way) to reduce poverty is to achieve and sustain higher economic growth rates. Analysts suggest that if Bangladesh has to make any significant impact on the existing poverty incidence, GDP growth at 6-8 percent will be needed. Under an optimistic scenario, a sustained growth rate of 6 percent will barely let the country achieve the target of halving the number of poor people by 2015.

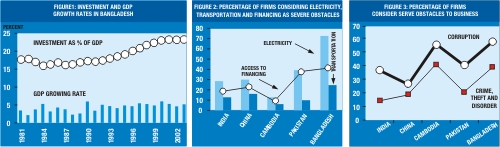

The objective of accelerating economic growth will critically depend on channeling increased resources into productive investment. Considering the experience of the past 20 years or so, it can be inferred that a growth rate of 7 percent would require an investment-GDP ratio of 31 percent as against of the current level of 23 percent. If investment is to be made out of domestic savings, it would imply that the current consumption is being sacrificed for future growth. When the overall income of a country is low, curtailing current consumption is a very difficult option. However, investment from foreign sources (such as FDI) can greatly help a country achieve higher growth without constraining the current consumption too much. For Bangladesh, raising the level of investment appears to be a critical necessary first step for improving the poverty situation. The post-MFA regime could make the task even more challenging. A fall in RMG exports would lead to loss of employment and output thereby adversely affecting the poverty situation.

One important factor in determining the prospect of higher investment is the socio-economic environment that influences returns from investment by private enterprises. When profitability of investment is hampered by such factors as macroeconomic instability, poor infrastructural facilities, deteriorating law and order situation, etc., potential investors will be discouraged from putting their resources into productive investment. Under such circumstances, only limited benefits can be materialized at the national level by the accumulation of resources by individuals. Given this backdrop, a lot of emphasis has been given to the importance of creating a sound investment climate in Bangladesh.

Investment climate is an idea, which is easy to perceive but difficult to define precisely. According to the World Development Report 2005, investment climate is the set of location-specific factors shaping the opportunities and incentives for firms to invest productively, create jobs, and expand. Clearly, this definition is very broad, which encompasses government policies, institutions and behavioural environment that have significant influence on costs, risks, and barriers to business. It has been emphasised that a good investment climate is the one that serves the society as a whole on the one hand (through its impact on job creation, lower prices, and broadening the tax base) and serves all firms, including both large and small, on the other. A sound investment climate not only encourages more investment but also promotes higher productivity because of increased competition. Consequently, the amount of investment required to achieve a desired level of growth may be less than what the previous experience suggests.

Many think that the investment climate is related to FDI only, which is not correct at all. For countries to achieve and maintain high levels of income and employment what is important is the total amount of investment irrespective of its foreign and domestic sources. According to the World Investment Report 2004, during the period 1990-2003, world FDI flows accounted for 8 percent of world domestic investment, suggesting that such flows only complement domestic investment. Even for China, which received an FDI flow of $53 billion in 2004, FDI comprised only about 12.4 per cent of gross fixed capital formation. This is not to undermine the importance of FDI, particularly when it reduces the pressure for curtailing the domestic consumption, but to emphasize the point that investment climate is equally important for mobilizing resources from domestic sources.

Macroeconomic factors, infrastructures (both physical and financial), and governance related issues, are considered to be the three main features of the investment climate. Over the past decade or so, Bangladesh performed well on macroeconomic indicators and achieved a steady economic growth with the record of an impressive macroeconomic management. It is now generally recognized that governance and infrastructure related issues act as more serious impediments to doing business in Bangladesh than macroeconomic environment.

The role of financial infrastructure is critical in the development of private sector enterprises. Finance is required to enable firms undertake productive investment in order to initiate and/or expand a business, to introduce new products and to market them. Availability of investment funds also facilitates acquiring better technology to promote competitiveness. However, one of the most important problems facing the firms in Bangladesh is the access to finance. In a recent private enterprise survey, as many as 58 percent of the surveyed firms reported the problem of lack of investment funds, while in the World

Bank investment climate survey it was revealed only 30 percent of working and investment capital was sourced from banks and financial institutions. The significance of the constraint related to finance was also reflected in a survey of some selected export-oriented firms, undertaken under the BangladeshExport Diversification Project (BDXDP), in which as high as 90 percent exporters reported the problem of accessing export finance.

The state of physical infrastructure in Bangladesh is considered to be one of the biggest causes for concern. Given the poor infrastructure, business enterprises spend more resources, both in terms of time and money, on such tasks as gathering information, acquiring inputs, and marketing their products. All this can undermine the competitiveness and returns to investment. There are two dimensions of poor infrastructure problem one is the unavailability of certain services or utilities (such as telephone, water, electricity, roads and highways, etc.) and the other is the unreliability of the services provided. A firm-level investment climate survey carried out by the World Bank in different countries confirms that the quality of infrastructure services is a more acute problem in Bangladesh, with electricity being the worst problem.

Ports and transportation are serious infrastructure problems. Bangladesh's main seaport, Chittagong, has long been considered as one of the most expensive routes to international trade due to labour problems, poor management, and lack of equipment. According to the World Bank investment climate survey, the Chittagong port container terminal handles about 100-05 lifts per berth a day, which is far below the productivity standard of 230 lifts a day suggested by UNCTAD; Ship turn around time is five to six days as against of just one day in more efficient ports; and the port faces serious congestion. Inland transportation also suffers from such problems as illegal toll collection, bad road communication, congestion at ferry-ghats, and frequent disruption in transportation due to political programmes. All this contributes to costs of doing business in Bangladesh.

Port and transport related infrastructural problems may have far-reaching implications. Recent research works on economic geography and international trade suggest that, as the geographical distance (hence transportation costs) between two partner countries increases, traded volumes tend to decline. A 10-percentage point increase in transport costs is found to reduce trade volumes by about 20 per cent. Consequently, increased transport

costs due to unfavourable geographical location alone can make a country's exports uncompetitive. The implication is that only because of their geographical location, some countries will experience much higher gains from trade and foreign firms might be reluctant to move or relocate their production to those countries that are far from their main export markets even when the wages in those countries are low. For the two major markets of the EU and the US, there are competitors, which are geographically better located compared to Bangladesh. Therefore, while geographical location puts Bangladesh at a disadvantaged position, inefficient ports and inland transportation further imposes penalties on firms' accessing foreign markets and acquiring imported inputs. Export-oriented firms, critically dependent on imported inputs, are the worst victim of these double disadvantages.

Governance is a big problem for firms in Bangladesh. Firms are often subject to excessive regulatory burdens while in other times there is a complete lack of regulation and monitoring both inappropriate for ensuring equity, establishing the rules of the game and protecting the consumers. Corruption is pervasive and according to the cross-country comparative index prepared by the Transparency International, Bangladesh ranks worst on measure of corruption amongst a set of global economies. More than half of the private enterprises covered in World Bank Investment Climate Survey in Bangladesh recognize corruption as a major or very severe obstacle to business and production. When cross country data are compared, proportionately more business firms in Bangladesh compared to those in Cambodia, China, consider corruption and crime, theft, and disorder as severe constraints. Enforcement of contracts and property rights are two important issues in private investment, but investors in Bangladesh have little confidence that the legal system can support them in case disputes concerning these two aspects arise. According to the cross-country survey data from the World Bank, while only 17 percent firms in Bangladesh reported of having some confidence in the judiciary system, the corresponding figures for India and China were respectively 70 and 82 percent. Destructive political activities, which are manifest in frequent disruption in production by political protests and strikes are also a big problem adversely affecting the investment climate. Apart from the issues mentioned above, other important factors influencing the investment climate in Bangladesh are: weak human resource base, use of obsolete technology, poor technological innovation, lack of free flow of information, and lack of entrepreneurship and management skills.

In the context of Bangladesh, there is some evidence of small and medium scale enterprises (SMEs) facing greater investment climate difficulties than their large counterparts. According to the World Bank survey, while about 34 percent investment funds of large firms come from the banking sector, the comparable figure for SMEs is only about 20 percent. The same survey also revealed that smallest firms tend to make unofficial payments (or bribes) at nearly five times the level of payments by large firms (as percentage of total costs). While a vibrant SME sector is often considered as one of the principal driving forces in the development of a market economy, higher investment climate costs could constrain their growth and development.

It follows from the above discussions that, Bangladesh will have to go a long way to improve its investment climate not only to attract FDI but also to mobilize more resources for investment from domestic sources. Improvement in infrastructural facilities and governance should be given utmost priority in bringing about a real change. In recent times some notable improvements in the customs and ports procedures in Chittagong have been accomplished as a result of which each export consignment now requires only 5 signatures by different officials as compared to 17 signatures required previously. Freight-forwarding charges have drastically been reduced. And, most importantly, waiting time for ports and customs clearance has declined significantly. Presently, the average typical wait for export is about 4.5 days compared to 9 days recorded during the World Bank invest climate survey in 2001-02. Similarly, the average typical wait for imports is now about 6 days as compared to 12 days in 2001-02. All this should have greatly contributed to reducing costs of business and is a pointer to the fact that it is possible to make things change in positive directions.

A number of attractive fiscal and financial incentives are currently available for investors, particularly for investing in 100 percent export-oriented units. However, there are formidable difficulties in actually accessing them. Therefore, along with the development of infrastructural facilities, there is a need for streamlining the management of the incentive systems.

One pragmatic way to improve the investment climate in Bangladesh may be to consider a well-devised integrated approach. Under this approach, actions required at different levels are brought together to make intervention measures or support systems comprehensive. Considering the problems faced by the business firms, various appropriate measures can be devised at three levels: (i) strategic or policy-making level; (ii) institutional level; and (iii) enterprise level. At the highest level, the policy makers with inputs from stakeholders may design appropriate short-, medium-, and long-term strategies to overcome the difficulties with the investment climate and to provide firm policy directions without any sense of uncertainty. Resource constraints would imply that some kind of prioritization will have to be determined at this stage in implementing the actions. The policy decisions will have to be implemented by the institutions. Operation of an effective and supportive legal and regulatory framework, effective management of public services, improvement of the managerial and entrepreneurial skills, development of human resources, etc. are the areas where the role of institutions is indispensable. Finally, there is no denying that the ultimate success in business depends on the efficiency of individual firms. Therefore, enterprises will have to be dynamic, innovative, and amenable to new ideas and ways of managing things.

....................................................

Dr Razzaque is Assistant Professor in the Department of Economics at Dhaka University.