Inside

|

Dhaka: A postcard from New Orleans Kazi Khaleed Ashraf paints a stunning portrait of how Dhaka can grow within its natural environs and provides a blueprint for what a Dhaka of the 21st century could look like.

Following the catastrophe wrought by Katrina last year many news commentaries in the US made Dhaka a cousin of New Orleans. The commentators wondered how a city like Dhaka gets pounded by flood year after year and still rebounds smoothly, while New Orleans sinks to the depth of disaster. Major studies and conferences sought answers to both, the origins of the disaster and ways of redemption for New Orleans. One consensus emerged that what was perceived to be the solution in fact compounded the problem. The levees and the embankments that were constructed for the protection of the city might have had a long-term adverse effect on the regional landscape. The wetlands and flood plains that characterized the landscape of New Orleans had increasingly been depleted, increasing the fury of Katrina. At the same time, the simultaneous subsidence of land under the city and the rise of the silted river bed made the levee project increasingly futile. Dhaka could ultimately face the same fate of New Orleans. The critical issue for New Orleans, as well as for Dhaka, is how to create a city in the flood-plains. This article summarizes the results of an exercise I conducted with my architectural class this year, to envision a long-term solution to Dhaka's age-old problems of flooding and over-crowding, taking into account the city's landscape and surroundings, as well as the geo-physical and demographic realities. All this "vision-making" was, of course, based on trying to understand the features of an intractable city. I have written elsewhere that Dhaka has five distinctive morphologies, or urban spatial patterns, with each pattern being the locus of a certain economic and social activity. There is first the pattern of the so-called old city, the seemingly chaotic and clustered mass of irregular buildings and spaces tumbling upon each other but, historically, harbouring a strong sense of community. Second, there is the model of the isolated bungalow on its wide spacious lawn, that characterized the official buildings and residences of the British, that projected a quality of airiness and greenness.

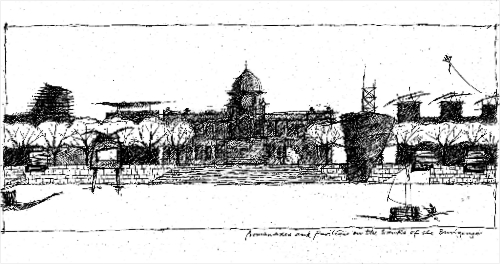

That model also spawned the third one with a tincture of modernist rationale, that of rows and rows of plots upon which were built isolated, independent buildings, that became known as the planned areas of the city, starting from Dhanmandi to Purbachal (the form of the former has now been transformed beyond recognition). The fourth morphology characterizes the half-planned, quasi-planned but mostly unplanned parts of the city, vast, amorphous areas often with inadequate or ineffective infrastructure. The fifth one is an invisible and unrecognized morphology, and yet vital to the visible city, one that spreads out across Dhaka, weaving in and out of the other morphologies, along the railways tracks, on the sidewalks and between buildings, inhabited by fresh migrants, vagrants, and generally by people at the periphery of planning. I have now come to realize that there is perhaps a sixth morphology, areas along the edge of a transforming city ringed by rivers, a dynamic edge that is constantly shifting where there is a constant tussle between urban culture and agriculture, between a proto-urbanism and a flood-washed landscape. It is that area that the Philadelphia studio targeted, an area that has come into greater focus due to the creation of a heightened and constructed edge: the flood embankments. The visions for Dhaka presented in the Daily Star anniversary issue were based on the following premise: "Dhaka is a child of the Buriganga, and yet it turns its back to the fundamental reality of being part of the world's most dynamic hydrological system. An audacious vision for Dhaka has to begin from where Dhaka began -- at the edge of the water. "How many of us realize Dhaka is almost like an island framed by three rivers, the Buriganga, the Turag, and the Balu? How many remember that canals used to crisscross older Dhaka? A ten-minute ride outside Dhaka still shows the aquatic reality of the land where flood plains and canals completely girdle the city. "A radical reclamation of Buriganga river and its banks on both sides is crucial for an economic, transport, and cultural reinvigoration of Dhaka. The river can become a sustainable life-blood, and the riverfront a much more organized area, providing renewed recreational, civic, economic, and transport facilities for the whole city in a way never witnessed before. "Instead of being fated as a third-world reality, Dhaka can be a very special city, a place by the river that works with water and vegetation to be a truly tropical city, one that is economically and ecologically sustainable, a unique, green and highly livable city. And all that despite the growing urban needs." The embankments, whatever job they are doing to control the incursion of flood-water, also raise a key question about the edge of the city, about marking a boundary between what will remain dry and what will stay wet. There is a great ecological and economic divide around that. It is within those premises of the sixth morphology, of the realization that Dhaka is an island, and that the city knowingly and unknowingly maintains a precarious relationship with a vast stretch of wetlands that are periodically flooded, that the architecture exercise focused on.

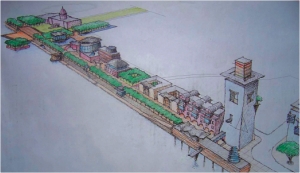

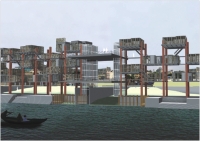

Site 1: Old Dhaka, begin at the beginning With such limited land at that site it seemed only natural to build on water itself. So the class introduced a continuous, porous structure that is meant to mediate between the growth of the city and the lack of land on the site. By looking at how indigenous buildings built on stilts were constructed along the river's edge they developed a grid system that ran all along the site. The introduction of a continuous element along the edge would create an ordering element that could counteract the random nature of the immediate city. The linearity makes it a place on its own and also connects it to the adjacent communities and streets. The consistent grid also allows a diverse set of activities to take place there. The uniform grid makes modular buildings possible, and also allows more organic parks and public spaces to be woven through it. The parks and public spaces are closer to the existing street level while the buildings are positioned on the upper levels, again with enough gaps and voids to be a perforated wall along the river.

Is it possible to relocate the dwellers at the southern tip of Kamrangir Char to a new set of structures and residences concentrated along the water's edge and return the rest of land to some form of experimental agriculture and parkland, wondered the students in my class. Can this exercise be a model for other farmlands adjacent to the river around Dhaka, where the agriculture-based community can be organized with as much land as possible devoted to agriculture while maintaining a close-knit and more physically organized community? The designers proposed creating designated agricultural land and canals in the central area, along with markets and parks that people from both the immediate area and the city can use. Housing will be devoted to a linear "wall" along the edge that will be both elevated from flood water (during dryer seasons, the lower area will work as a promenade), and perforated enough to be a screen-like structure on the river's edge. Residents can use a kit of parts and, following a set of rules, can create their own individualized dwellings. Site 3: On the flood-plains It represents a rapid transformation of an area between the river Buriganga and the embankment where a thoughtless and ecologically disastrous urbanization has taken hold.

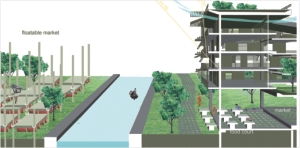

An area that was characterized by an intricate network of canals, ponds, agricultural fields and wetlands all ultimately linked to the river is being aggressively changed simply by land-filling and creating dubious "housing societies," a process that marks the so-called urbanization of Dhaka all around its edge. The aim of the class was how "to bring the city into the flood-plain and the flood-plain into the city." They focused on an existing canal on the flood-plain side of the embankment and used that as a main organizer. They proposed to re-establish the canal within the city-side (which has been ingloriously filled up) and thus unify the city by a waterway, reminding the citizens that they live in a waterborne city. The class proposed a new network of cautious and careful development -- streets, walkways, housing and public places -- that was mostly elevated either on stilts or non-continuous earth mounds over agricultural fields, gardens and parks, each at different elevations and responding to different levels of flooding. The porosity at the lower level allowed an unimpeded flow of water at different seasons. While this is a very provisional idea, it offers the potential to think of a very different urban morphology on such a landscape -- a more or less stable urban form overlaid over a fluid landscape.

Site 4: Near the Martyred Intellectuals' Memorial Their key question was: How does one inhabit the water? Seeing how important the cyclical water flow and management is to Dhaka, they decided to blur the fabrics between land/water/human by fragmenting the embankment at points. They proposed this in two ways: one, by creating a designated "green/water" buffer between the embankment and the built city characterized by wetlands, reservoirs, retention ponds, and parks; and, two, by tentatively building up on the side of the floodplains (with the Bashila Road embankment as the first attempt). In the second scheme, people would be connected through a series of circulation paths: an organizing device which would ultimately generate a more diverse palette of leveled spaces for multiple uses (park, agriculture, and housing).

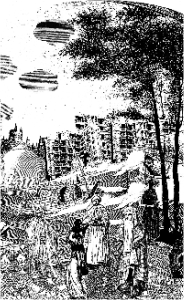

Where the river bends close to the embankment, a major commercial and transport node is suggested. The flood-plains will also be reorganized for designated areas for rice cultivation, elevated fields for, perhaps, orchards and rose cultivation (that will also be accessible as parks via boat or bridges from the ribbons), and permanent canals for boat-ways, both along and under the ribbon-structures. Site 6: Gabtali, a gateway to the city The class worked on a very specific location close to the river and the existing bridge to reorganize part of this chaotic, but otherwise vital, area into a glorious gateway to the city. By creating a set of buildings that blur with the landscape, they proposed morphing the geology of the site. Most of the buildings will house hotels, markets and commercial uses, with sloped roofs covered by greenery. All the roofs will be open and accessible and will be connected to create a continuous public space. Another morphing will involve creation of a small island across a new canal aligned with the landscaped buildings. The island will be for multi-purpose use including temporary stalls, a stage, and a seasonal cattle market. Floatable platforms tied to a structural grid will allow activities to continue even when the island is flooded.

Site 7: Moulding a primordial landscape The class suggested a bold idea about the existing embankment there. They initially made some studies of how silt and clay are part of an ongoing land formation, and how some simple architectural gestures -- such as a wall -- in the path of the river may spawn new land formation. They proposed deconstructing the existing embankment into a series of more interlocked walls, planes and platforms, creating a new grid of lines and bounded areas. The result was a new framework where water from either side -- city or river -- could be allowed passage in either direction in a controlled way within the gridded spaces through locks and sluice gates to create retention ponds, reservoirs, parks, or agricultural fields as needed. The new interlocking "walls" could be a platform for creating housing structures over a continuous pedestrian or vehicular movement system. Kazi Khaleed Ashraf teaches at the University of Hawaii in Manoa. The study for this article was conducted with the following students: Kyle Solyak, Daria Cheentsova, Max Lent, Sara Vasquez, Marcello Schiffino, Grace Barber, James Gianfrancesco, Jamie Lynn Murray, Ayako Okutani, Jamie MacDonald, Andy Allwine and Emma Jesko while Prof Ashraf was a visiting professor at Temple University in Philadelphia in 2006. |

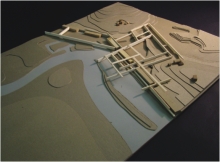

Seven sites of intervention were selected along the western embankment of Dhaka, strung all along its length from near Showari Ghat area, the oldest part of the city, to the area up in the north at the Mirpur botanical garden. Each site was carefully selected, with its immediate peculiarities and special conditions in mind, to address a whole series of issues for the edge of Dhaka.

Seven sites of intervention were selected along the western embankment of Dhaka, strung all along its length from near Showari Ghat area, the oldest part of the city, to the area up in the north at the Mirpur botanical garden. Each site was carefully selected, with its immediate peculiarities and special conditions in mind, to address a whole series of issues for the edge of Dhaka.

Site 5: At the bend of the river

Site 5: At the bend of the river