Inside

|

The twilight of caretaker governance? Are we seeing the end of the caretaker government system, and what are the implications of the current crisis for the long-term political future of the country, asks Rehman Sobhan

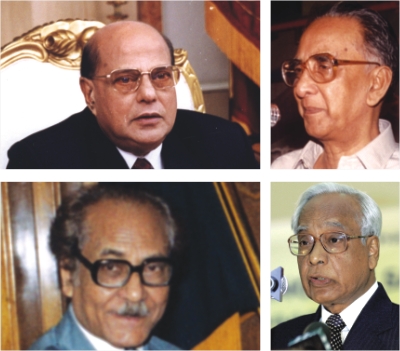

The idea of a caretaker government (CTG) originated in the apprehension of political parties in opposition as well as a large segment of citizens that a regime in power could not be relied upon to hold free and fair elections. In both Pakistan and Bangladesh there is a long history of "managed" elections to support the logic for a CTG. The amendment to the Constitution of Bangladesh enacted in April 1996, institutionalizing a caretaker government was, thus, widely appreciated in the country and hailed in many countries around the world victimized by the partisan conduct of elections. We now, sadly, appear to be witnessing the possible twilight of the caretaker government system which filled us with so much hope for Bangladesh serving as a global role model for free and fair elections. The decision of the Grand Alliance to boycott the January 22 election on account of their perception of the partisan character of the chief advisor and the resultant loss or confidence in the CTG to preside over a free and fair election has turned the clock back to the last days of 1995. At that time there was a widespread demand for elections under a non-party caretaker government. The failure of the ruling BNP to respond to this demand and the resultant boycott of the polls by the Awami League-led alliance did not deter the ruling BNP regime from holding a one-sided election in order to ensure constitutional propriety. This led to a voter-less election in February 1996, the subsequent constitutional amendment for a CTG, and the eventual electoral defeat of the BNP in the June 1996 election. The main difference between 1996 and 2007 is that it is the very institution of CTG, which was seen as the political panacea for escaping from partisan elections, which has invoked a boycott of the January 22 poll because of its perceived partisan character. Can CTG survive this gradual erosion of its institutional credibility? The prospect of the demise of CTG is a painful thought for me, personally, since I participated in the first CTG headed by Chief Justice Shahabuddin Ahmed. Our period of caretaker government was a period of renewed hope, after the downfall of the Ershad autocracy, for the prospect of restoring a democratic order. The first CTG enjoyed universal acclamation for the impartiality with which it discharged its mandate which culminated in the organization of an election which was deemed by many as the freest and fairest ever witnessed in Bangladesh. The success of the Shahabuddin CTG did not originate in its constitutional mandate but in the commitment of its head to play a genuinely non-partisan role in the conduct of his governance. The council of advisors under President Shahabuddin functioned as a consultative body, where all issues relating to the election as well as governance of Bangladesh were fully discussed in the meetings of the council. This was particularly remarkable because President Shahabuddin, on his own accord, invited only a few highly respected senior persons to serve on the council. The majority of the council members sat on the advisory council as nominees of particular parties or alliances, so the council could have been an arena of discord. It was again the democratic way in which Shahabuddin conducted the CTG that ensured that no conflicts divided the council and that all decisions were based on democratic consultation and were consensual. Since President Iajuddin Ahmed and I were colleagues on that council, he is as aware as I am of how a truly democratic council functions. The subsequent two CTGs functioned under the provisions of the constitutional amendment enacted in April 1996. The amendment mandated the chief advisor to be a non-partisan person and to govern during his/her tenure in consultation with the members of the advisory council. The CTG under both Chief Justice Habibur Rahman and Chief Justice Latifur Rahman functioned on a consultative basis in which particular advisors were delegated responsibility by the chief advisor to oversee critical areas of governance such as Home, Establishment, Foreign Affairs, and Law. The outcome of the elections under the three CTGs caused some discomfort to the defeated parties, particularly after the 2001 election. However, in the final analysis, no one questioned the legitimacy of the regime elected to power in 1991, 1996, and 2001, largely because the chief adviser, at the time he assumed office, was deemed by all parties to be a non-partisan person. During the actual tenure of the three CTGs no party questioned the non-partisan character of the chief advisor or the CTG, though particular actions may have aroused misgivings among particular parties. This tradition of non-partisan CTG appears for the first time appears to have been disrupted during the tenure of President Iajuddin Ahmed. The president, assumed the office of the chief adviser through a constitutionally questionable coup de main. No adequate explanation has been given as to why he by-passed the available options either from the judiciary or by looking for a distinguished citizen. The most serious challenge to the Constitution, however, originates in his partisan origins. To self appoint a person such as President Iajuddin, with a long standing affiliation to a particular party, to hold the office of chief adviser, was deemed by many jurists as well as citizens, as repugnant to the spirit and possibly the letter of the Constitution which clearly states that a non-party caretaker government, with a chief adviser at its head, shall hold office after Parliament is dissolved. The legality of this assumption of the office of chief adviser by the president was challenged in the Appellate Division where a clear judicial opinion would have tested the constitutionality of the action. Unfortunately, the voters were denied the opportunity of such a judicial opinion by the extraordinary intervention of the chief justice who issued a stay order on the proceedings in the High Court. This deviation from the constitution could have been politically tolerated had the president, transcended the confines of his political loyalties and attempted to conduct himself as a genuinely non-partisan chief adviser. However there now appears to be a degree of evidence, which was testified by the quite unique resignation of four members of his advisory council, to suggest that the chief adviser was performing his duties in a less than non-partisan manner. The resignation of the four advisors did not just originate in their apprehension of being associated with a partisan administration but in their perception that the president had reduced the advisory council to a subservient role which was contrary to the basic tenets of the institution of caretaker government. Some examples of the perceived undemocratic conduct and partisan bias of the decision making process under the CTG, which were discussed in the media, are presented below: * The appointments of two new members of the Election Commission after the leave of absence of the Chief Election Commissioner Justice M A Aziz. These appointments by-passed the council and at least one of the appointees was politically affiliated to the 4 Party Alliance. *The direction by the chief Advisor, without consulting his advisors, to the chief election commissioner, to set a date for the elections. *The repudiation of the "package" agreement negotiated by some members of the advisory council with the principal political alliances. This "package" which was prepared though extensive consultations within the advisory council, presided over by the chief advisor, in fact carries the signatures of all members of the advisory council including the chief advisor. *The deployment of the army, contrary to the explicit advise of the members of the advisory council. *The retention of some of the key portfolios of Establishment, Foreign Affairs, Home, and Law by the chief advisor. In the previous CTGs these portfolios were typically assigned to particular members of the advisory council and such portfolios as law enforcement overseen by a committee of advisors. In the present CTG the chief advisor made himself chairman of a number of such key committees, and then, in his executive capacity, by-passed particular decisions of the committee, because of his control over the particular ministry. *The decision to advise the attorney general to move the chief justice in his residence to over-ride the judgment of the Appellate Division on the legality of the assumption by the president of the office of chief advisor, by issuing a stay order. This important action took place with consulting the advisory council. Many more such examples of decision making by the chief advisor, bypassing the council or overriding the decision of the oversight committee of the council, could be cited and will no doubt come to light when the full story of this sad phase in our history are brought to light. Whilst debate may continue about the facts and circumstances governing the conduct of the chief advisor, such perceived undemocratic and partisan conduct strikes at the very foundations of CTG, thereby compromising the credibility of the forthcoming elections. In the eyes of the Grand Alliance and possibly a much wider public, for all practical purposes, the present chief advisor may no longer be deemed to be presiding over a non-party CTG but appears to be perpetuating the mandate of the 4 Party Alliance. The reconfigured advisory council, following the resignation of four of its members, appears to have visibly lost its independent voice and now seems to be functioning largely as the mouthpiece of the chief advisor, which in effect has eroded the non-partisan character once projected by the CTG prior to the exit of the four advisors. The inability of the CTG to project a non-partisan identity seems to have impacted on the actions of the Election Commission. Notwithstanding the leave of absence of the Chief Election Commissioner, Justice Aziz, and the belated leave taking of SM Zakaria, the remnants of the Election Commission appear to feel no pressure from the CTG to project the transparency and ensure the credibility of the forthcoming elections. The Election Commission, thus, appears to lack the urgency, motivation and competence to preside over a genuinely free and fair election. Within the time available to it the commission is unlikely to fully correct the electoral roles before the polls which will seriously compromise the credibility of the election and according to Justice Naimuddin Ahmed may even be constitutionally challengeable. As far as the Grand Alliance is concerned, they have lost all confidence in the Election Commission. Decisive action by the CTG in 2001 in reshuffling the administration at all levels gave clear signals to all members of the administration, that the CTG was determined to ensure a free and fair election. A certain amount of reshuffling of the administration by the CTG has perhaps taken place but these actions have generated no confidence within the Grand Alliance that the administrative architecture put in place prior to the resignation of 4 Party Alliance has been reconstructed to ensure a non-partisan character to the administration. Crucial positions such as the office of the attorney general or the heads of the security agencies or at the crucial district, upazilla, and local level where the actual conduct of the election is overseen, have been largely left intact. As a result Grand Alliance electoral candidates perceive much of the administration at the national as well as local level as a continuation of the outgoing government in all but name with a clear interest in seeing the 4 Party Alliance returned to power. Prospective candidates from the Grand Alliance claim that their party workers are being arrested by the law enforcement agencies as was the case during the tenure of the outgoing government.The prospect of relief from the judiciary for those seeking justice from partisan governance appears far from assured. The way in which the judicial process was used, first to give relief to HM Ershad when he opted to join the 4 Party Alliance and then to reactivate his corruption cases when he opted for the Grand Alliance, suggest that the law has now assumed a partisan hue. The same attorney general's office which expedited the withdrawal of cases against Ershad during his honeymoon with the 4 Party Alliance is now seeking to rush to judgment now that Ershad has changed his alliance. Since these same officers of the law who served the 4 Party Alliance are now serving the CTG, the partisan bias in the conduct of their duties impacts on the credibility of the CTG. The response of the two alliances In seeking to challenge the bias in the CTG towards the 4 Party Alliance, the 14 Party Alliance set out to build a Grand Alliance bringing together some odd bed-fellows, ranging from Ershad and the LDP to some of the more extreme fringe groups of the fundamentalist parties. Such a Grand Alliance has now assumed a rather heterogeneous character with little political or ideological coherence. The rather unprincipled compact of the Awami League leadership with the fringe group of fundamental parties was not one of the more glorious moments in its long history as a leader of the forces of secular politics. This manifestly opportunistic move has demotivated many of the AL's followers, particularly from civil society, and alienated some of its vote banks. In return, the prospect of political gain by the AL appears questionable since their new allies are hardly significant vote winners. Until January 4, the 4 Party Alliance for obvious reasons, felt that the tide was flowing their way. They have seen a person who was casually affiliated to the BNP a quarter of a century ago, replaced as chief advisor by a serving loyalist with deep-seated obligations to the party. They have seen virtually the entire administrative structure they put in place before they left office, down to the grass roots level, still in place. They have witnessed the resignation of four members of the advisory council who were willing to play a non-partisan role and the silencing of those from the advisory council who were once willing to also speak their mind. The four out-going advisors have been replaced by advisors either of proven loyalty or those with a talent for providing comic relief. Whilst Aziz and Zakaria may have gone on leave the incumbent acting chief election commissioner appears to show little capacity for decisive action whilst Mudabbir appears to have been a 4 Party Alliance member seeking an election ticket. In their moment of triumph the 4 Party Alliance should have had the good sense to conduct themselves with The crisis for democracy The mandate to hold elections in 90 days is undoubtedly important but this goal is subordinate to the primary mission of the CTG to hold a free, fair, and peaceful election, participated by all the parties where the outcome represents the authentic democratic mandate of all citizens eligible to vote. The notion that in order to hold elections within the stipulated 90 days, with or without the participation of a significant part of the political spectrum, the CTG will need to deploy the full force not just of the law enforcement agencies but the armed forces is an affront to the very concept of democracy not to mention commonsense. Any dictator or autocratic ruling party can order a one-sided election held under the guns of the armed forces. We have witnessed such elections in the past. But such a militarized approach to the electoral process is repugnant to the spirit and indeed the constitutional mandate of the CTG. Preserving the democratic process *The resignation of the president from his position as chief advisor. *The identification and appointment of a chief advisor by the president, who is acceptable to all parties. *An agreement on a new date for the elections, possibly 60-90 days from now. This would be backed by a reference to the Appellate Division, to which both alliances would be signatories, seeking a constitutional dispensation for rescheduling the elections. *The reconstitution of the original council of advisors who in their original incarnation performed a commendable role. *The appointment from within the above advisory council of a committee chaired by one of the advisors, to oversee the restructuring of the administration prior to the elections, to ensure the non-partisan conduct of the elections. *A commitment by both the alliances to abjure from calling hartals/oborodhs during the tenure of the CTG *A commitment by all parties to abide by the results of the elections and to participate actively in the next Parliament. *The commitment by the two alliances to honour their commitment to nominate "clean" candidates. *The constitution of a national election monitoring body, which brings together the entire spectrum of civil society institutions, to oversee the elections in every polling center. *A massive and unified deployment of international observers, led by an internationally recognized personality, such as Presidents Carter or Clinton or former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan, to monitor the elections. *A commitment by both alliances that whomsoever wins the elections will abjure from acts of vengeance and violence on their defeated opponents. If wrong-doings have been committed by members of either alliance, this will be addressed through the due process of law and not arbitrary administrative or vigilante actions. The above suggestions can be elaborated and/or modified. The operating issue is that both alliances need to sit together to resolve the issue of preserving democracy once and for all. Their commitment to put aside the bitterness and anger, which pathologically divide them on almost tribal lines today, will depend on whether they remain committed to the preservation of democracy and the institution of CTG. If either party is motivated by other, unspoken agendas, then we may well be seeing the end of caretaker governance and the dawn of a dark age in the blighted political history of Bangladesh. Rehman Sobhan is Chairman, Editorial Board, Forum. Photos: Star |

more finesse. They could have accepted the original "package" or conceded an extra day for filing nominations or deactivated the serviceable attorney general's office from frustrating the opportunity for HM Ershad to contest elections. But in their moment of triumphalism they seem to have overplayed their hand. Both the leadership of the 14 Party Alliance and even more so, HM Ershad, were keen to contest elections, even on January 22, in spite of the opposition of many of their principal lieutenants and allies. The Grand Alliance was prepared to go to the polls, on such uneven terms, had the HM Ershad affair not been played out. In this final play the 4 Party Alliance appear to have not only undone what they had achieved through more tactical political

more finesse. They could have accepted the original "package" or conceded an extra day for filing nominations or deactivated the serviceable attorney general's office from frustrating the opportunity for HM Ershad to contest elections. But in their moment of triumphalism they seem to have overplayed their hand. Both the leadership of the 14 Party Alliance and even more so, HM Ershad, were keen to contest elections, even on January 22, in spite of the opposition of many of their principal lieutenants and allies. The Grand Alliance was prepared to go to the polls, on such uneven terms, had the HM Ershad affair not been played out. In this final play the 4 Party Alliance appear to have not only undone what they had achieved through more tactical political  and, preferably, during the tenure of the next elected government.

and, preferably, during the tenure of the next elected government.