Inside

|

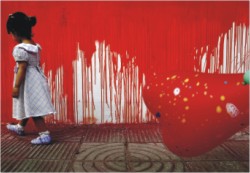

A civil war of the soul The bitter and on-going struggle that has defaced Bangladeshi politics since its inception is nothing less than a civil war for the soul of the country, writes Nadeem Rahman

Once upon a time, it was said that: "What Bengal thinks today, India will think tomorrow." Sadly, that is no longer true, and neither "lesser" nor "greater" Bengal can any more claim the limelight as prima donna of political adventurism in South Asia. What is true is possibly almost exactly the opposite, as Bengal implodes in a journey of self-discovery and inevitable rebirth. This is not to imply that such a sojourn is necessarily either regressive or, in any manner, degenerate. On the contrary Bengali renaissance survives, and the instinct for self-expression acquires new dimensions with each new experience. However, unlike a text-book intellectual awakening, the frontiers of philosophy today are a living phenomenon affecting almost every aspect of ordinary lives. In Bengal the battle for doctrinal supremacy is an interactive theatre. The drama is deadly serious, with potentially disastrous consequences -- and abundant opportunity for rewarding self-fulfilment. The challenge is communal and collective, as well as intensely personal. In these extraordinary times, when uncensored liberalism must defend itself from the point of the sword, conscience alone is no match against the fury of the fundamentalist. Thus, self-discovery is more often then not reduced to self-preservation, and "enlightenment" under siege can, at best, light the path to the nearest safe sanctuary. This bitter struggle is the struggle for the soul of Bangladesh. This search for identity is nothing less than a civil war of the soul.

Are we merely medieval Muslims or sophisticated secularists? Are we truly the children of freedom, or simply slave labour, bought and sold by the gangsters of political propaganda? Is Bangladesh arguably only an overloaded ark on the high seas of history, with no dearth of self-acclaimed captains, but without a star to steer her by? Are we, the Bengali people, a failed nation-state, and, if so, where lies the redemption? In our quest for clues and lost opportunities dare we delve into the faded memory of undivided Bengal, and the still-birth of a broader vision which might have fathered richer, more versatile demographics? Be that as it may, despite the historic betrayal and even in the absence of residual Bengal, the questions posed remain valid and relevant in the context of free Bangladesh. Many eagerly await the demise of our dreams.

A Bangladesh consigned to the dust would justify a wealth of war crimes, discrimination, and historic abuses. It would amount to a grotesque reversal of history, and the triumph of injustice on a grand scale. A failed state, therefore, is not an option. Quite the contrary, it is a luxury which no one deserves, neither the "losers," nor the onlookers, who will ultimately be obliged to pick up the pieces. More importantly, the imagined scenario of the imminent collapse of the entire edifice of Bengali society, culture and economy, is as removed from reality as are the far-fetched visions of a "Switzerland of the East." If I sound cynical, perhaps even a little pessimistic, permit me to contradict myself. A dispassionate appraisal of Bangladesh's performance on the world stage is sure to surprise those already conditioned to the much publicised image of a destitute "basket case." In fact, it will reveal a nation in ascent which has outstripped even the most extravagant predictions of her potential. Let us count our blessings: * Bangladesh is the first and only country in the world to completely eradicate polio.

This splendid showcase of successes is simply the prelude to the continuing chronicle of our humble achievements. But, above all, Bangladesh is the birthplace of micro-credit, the home of the largest and most productive NGO in the world, and the initiator of South Asian Association for Regional Co-operation. Its successes touch every facet of development, from agriculture, industry, commerce and banking to human resources. Bangladesh has distinguished itself in the field of non-traditional exports, such as ceramics, garments, leather goods, sea- food, etc. Bangladeshi white and blue-collar workers are to be found on every continent. Bangladeshi diplomats have made valuable and significant contribution to the United Nations, NAM, the OIC, and the Commonwealth. Bangladeshi troops have kept the peace in 26 countries around the world, from Bosnia to the Congo. Bangladeshi sportsmen have enthralled their compatriots with a stunning victory against the world champions of cricket. The people of Bangladesh have amply demonstrated their preference for change of governments through constitutional means and, when all else had failed, successfully overthrowing our own home-grown despots without inviting an invading army. One can only conclude that Bangladesh is visionary and inspirational and passionately indomitable. Without a doubt, she has earned her rightful place in the community of sovereign nations. Only one obstacle stands in the path of Bangladesh and her destiny: Politics! After a life and death struggle for freedom and social justice the political culture of liberated Bangladesh has come full circle, from total revolution to total failure. Two assassinations in two decades of disastrous political misadventure, corruption and misrule have completely crushed the spirit of "liberty, equality, and fraternity." One cannot overstate the damage to the national psyche. All the idealism and all the heroism and all the patriotism could not diminish the deluge of dashed hopes. Since then, societies for secret killings are an open secret, libel and slander are liberally exchanged and "status" is traded with ruthless jealousy. Unconstrained by tradition and social custom, "liberty" has come to mean the licence to indulge in every desirable evil, untouched by the long amputated arm of the law. Since then, the silent majority of innocent by-standers lives in constant fear of the feuds between colliding ambitions, and the arrogance of easy money. The endeavours of ordinary citizens stand for nothing, and decency is condemned to solitary confinement. Streets are the seats of learning where our children are apprenticed in the crafts of violence. Legality is denied independent dispensation, while political patronage tips the scales of justice. Freedom of the press is not infrequently silenced by lethal "rejoinders." While the holiest of holies, religion, is embraced with lust by passionate power-seekers. When ignorance and arrogance complete a fatal attraction, any crudity is conceivable. Power is the end game -- the first and last game. Nothing takes precedence over the acquisition of absolute authority. This appetite is no less fundamental than religious fanaticism, ideology or tribal loyalty. It is the driving force behind the grand charade of political manifestos, and the elaborate pretence of the common weal. In the spirit of this all-consuming philosophy our leaders remain inflexible to the bitter end, demolishing everything in their path. Political parties are glorified cult followings that ritualistically echo their masters' voices, and offer little to choose between one above the other. None of them displays even a spark of imagination, and all are equally enthusiastically aggressive and obsessively confrontational. What is worse is the fact that there is no reason to expect any change in the political climate, since intolerance and intimidation are the tried and tested formula for success. The rest is history. Under these conditions it seems totally unnecessary to repeat the litany of sins of the mighty -- the endless strikes, the refusal to negotiate, the abuse of power, the harbouring of criminals, the armed cadres, the personal vendettas, the complete disregard of the rule of law and, of course, the infamous corruption. Needless to say, none of this is news to anyone anymore and all of the above apply equally to all the usual suspects, whether in office or in the opposition. Compromise, accommodation and consensus are words that have been deleted from the dictionary. Instead, the politicization of every organ of government, the breakdown of law and order, the absence of accountability and the "modest" veiling of transparency, have become the accepted norms of "good" governance. The alternative represents a Utopian ideal, consisting of cliched catch phrases that no longer bear any meaning whatsoever, even to a single foot-soldier on the battlefield of political Bangladesh. Predictably enough the arch combatants will readily agree, but only when the evils of "bad" governance are applicable to their arch rivals alone. Despite the electorate's clear message every five years our political elite remain unrepentant and supremely confident of eluding the judgment of history. Public opinion, of course, is completely irrelevant. So much for liberty, equality and whatever else … Perhaps, at the end of the day, we may yet evolve a system more in tune with our heartbeat so that we might fill with good and tangible goals the void of so many empty promises. Until then politics. as it is presently practiced, will continue to act like a wedge between the rulers and the ruled, and strike at the heart of the disinherited. Whatever the reasons, the consequences are critical -- these are the roots of alienation. An entire generation, which has never known anything better than the grime of its miserable existence, is literally disenfranchised from any hope whatsoever. While a new age of the hierarchy of wealth reinstitutes the old class structure with renewed vigour. The new morality of the newly ultra-modern is on a collision course with established conservatism and age-old poverty. Thus, the hunt for identity is the choice between the lure of the consumer culture, and the promise of clemency for all our crimes of passion, with just the pulling of a trigger. There is no middle path. The identity goals are crystal clear and uncompromising. The pressures are irresistible. Whichever way we package the agenda, whether in the emergence of the proletariat or in the resurgence of religion, the message is incendiary and unambiguous. Some who have fought in Palestine, Afghanistan, and other frontiers of Jihad, have returned, bringing with them the scars of a foreign crusade, only to become misfits and lost souls in their own homeland. Such men will not easily surrender their convictions, simply to conform with countrymen who, in their eyes, have strayed from the true path. They will stand their ground. For them liberal democracy is a giveaway, a total sell-out. After all, in a nation of nearly a hundred and fifty million, how many truly understand the meaning of such a long-winded word as secularism? Others have just stepped out of their villages, bombarded by satellite television and the spoils of party affiliation. These are the "secular" infidels, the corruptible "faithful." But both, however incompatible, share a common determination to demolish the status-quo and become the ultimate arbitrators of their own fate. We can blame the failure of leadership, the dogmatic disciples; we can blame colonialism, the economic superpowers, globalization and the ubiquitous multi-nationals; we can blame our neighbours, the wolf at the door; we can blame religion and the war on terror; we can even blame democracy, but none will rush to our rescue, nor defuse the time bomb of our fortunes. The sum total of all our fears is only the tip of the iceberg. The deciding battle for Bangladesh will be fought, not only between the haves and the have-nots, but between institutionalized beliefs and the open society, between the power of superstition and the freedom of individualism. It will wake the dead and challenge Bengali nationalism to the core. What manner of men we are, our emotional resources, our intellectual depth, our strength of character, the vastness of our magnanimity, will define the face of freedom -- or the mask of tyranny. In the civil war of the soul, socialism and Islam have much more in common with each other than with any of the non-existent "philosophies" of the bickering political parties of Bangladesh. The al-Qaeda franchise, no less persuasive than Coca-Cola or McDonalds and other symbols of Western civilization, is by no means the exclusive marketing agent of "resurgent" Islam -- nor is the rise of the working class a sinister communist plot to discredit the efficacy of faith and establish a godless society. It is simply the inevitable triumph of humanity over bad masters. This fever will not be slaked. It is, after all, the fever of the soul. Our heroes, the pundits of political prophesy, should take heed lest they, too, are swept away by the very revolution they helped to ignite. One is reminded of the words of an English historian: "In a darkness deepened by contrast with such radiance might be perceived a monarchy at once despotic and weak, a corrupt and worldly Church, a nobility growing increasingly parasitical, a bankrupt exchequer, an irritated bourgeoisie, an oppressed peasantry, financial, administrative, and economic anarchy, a nation strained and divided by misgovernment and mutual suspicion -- all the factors … which lead a country to revolution." Nadeem Rahman is an author and poet. This is an extract from his forthecoming book "Not In Our Stars" to be published by Academic Printers & Publishers Library. |

To exorcise the dilemma and recognise ourselves in the chaos of conflicting cultures it is important that we search our souls and ask, in the words of the French painter Paul Gauguin: "What are we, where do we come from and where are we going?" The Bengali species is suicidal in the pursuit of its dreams, and can, therefore, reasonably look forward to the respect of all those who cherish a dream and an unbiased examination of our vices and virtues, our aspirations and inhibitions, against the backdrop of history: Are we still the intellectual giants we once thought ourselves to be, or vestiges of a wistful wisdom feverishly improvising an evolving Bengali nationalism -- a nationalism bereft of at least half its "legitimate" natives -- half Bengali, half Indian!

To exorcise the dilemma and recognise ourselves in the chaos of conflicting cultures it is important that we search our souls and ask, in the words of the French painter Paul Gauguin: "What are we, where do we come from and where are we going?" The Bengali species is suicidal in the pursuit of its dreams, and can, therefore, reasonably look forward to the respect of all those who cherish a dream and an unbiased examination of our vices and virtues, our aspirations and inhibitions, against the backdrop of history: Are we still the intellectual giants we once thought ourselves to be, or vestiges of a wistful wisdom feverishly improvising an evolving Bengali nationalism -- a nationalism bereft of at least half its "legitimate" natives -- half Bengali, half Indian!