Inside

|

Honesty = Success, Dishonesty = Failure An overview of power sector unbundling in Bangladesh (1996-2006) Sharier Khan runs a critical eye over the power sector operations of the past ten years and compares the performance of the AL and BNP governments.

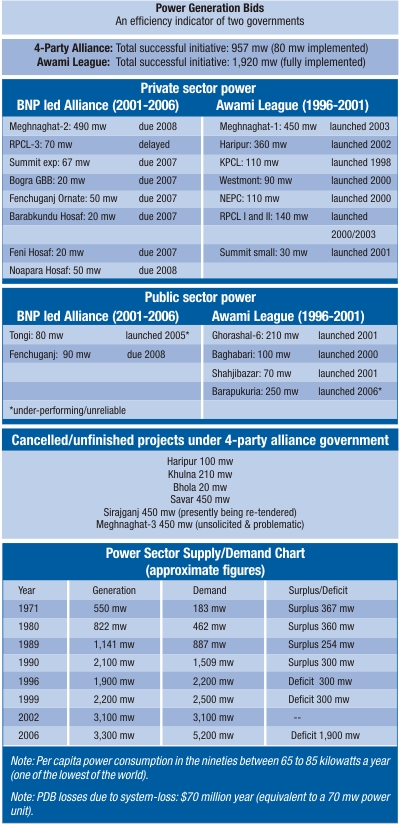

When Bangladesh was born in 1971, the impoverished nation's economy was entirely dependent on agriculture. There was almost no industrial activity. A country of 70 million people consumed only 183 megawatts of power. But by 1990 the country was slowly advancing in diversifying its economic activities. When democracy was restored in 1991 the country's power demand rose to 1,500 megawatts, and it still had 300 mw surplus power. Till this time, the capital intensive power plants were built under loans, grants and even barter trade agreement with donors and friendly nations. Democracy changed everything in the power sector. The demand for power suddenly started rising while lack of funds, primarily, contributed to lack of supply growth. Besides, at the policy-making level there was a lack of understanding of the importance of the power sector to the economy. Between 1991 and 1996, a couple of power projects, such as the Raozan 210 mw plant, were implemented. But their quality was very poor because of built-in corruption in the deals. As the first democratic government in two decades, the BNP failed to add adequate new power plants by the time it left power. The country was facing perennial power crisis when the second democratic government of the Awami League came to power in 1996. However, the BNP government had done some ground-work on reforming the power sector. It framed a 20-year Power Sector Master Plan (PSMP) that would later act as the road-map for the sector's development, and also initiated the process to involve the private sector in power generation and drafted a private power policy. When the new government came to power in 1996, the power scenario was grim. The government, for the first time, attached high importance to addressing the situation as fast as possible. Given the odds, this political commitment made this government the most successful in the power sector in the history of the country -- though that success is not fully free of controversy. Because of this commitment the country succeeded in securing private power deals through open international tender, totaling more than 1,100 mw, without a single re-tender or any allegation of bid manipulation. Of them, agreements on two major projects gave Bangladesh one of the lowest power tariffs in the world. Above all, it has proved that open tender and transparency work. In contrast, the next BNP government failed to lead in the power sector and surrendered to corruption, proving that bid manipulation and opaqueness fail to generate anything for the nation. Era of Private Power At the same time, the government was also implementing some public sector power projects under the controversial supplier's credit scheme. PDB floated the first tender for barge-mount plants in five areas of the country in late 1996, and as many as 39 companies expressed interest. PDB signed its first deal for a 114 mw plant in Khulna in mid-97. Within a few more months it signed three more deals. These deals would add more than 400 mw power to the national grid within 10 months of the agreement. The first 114 mw barge-mount power plant, US company Wartsila-led Khulna Power Company Ltd, was commissioned in October 1998 -- several months behind schedule. Two other companies, NEPC and Westmont, commissioned their plants in 1999, many months behind schedule. A fourth barge-mounted deal fell flat. Barge-mount schemes are not very cost effective as they charge around 5.2 cents per unit of power -- which is much higher than that of the large land-based power plants. This tariff is, again, set on the condition that the barge-mounted plants be given tax-free imported fuel oil (in contrast, PDB run barge-mount plants do not get tax-free fuel oil). The government has also agreed to supply these barge-mount plants with cheap natural gas in the near future. When this supply starts (the government would bear the gas pipeline cost), the power tariff will slip down to 4.6 cents. Former PDB Chairman Nuruddin M Kamal has explained to the press that the barge-mount projects were delayed because of the government's inexperience in conducting negotiations with private parties, and also the inefficiency of the private companies in ensuring project finance within the agreed schedule.

Success Case Study I: US company AES was the lowest bidder in the Meghnaghat project as it proposed a "levelized" (or average) 22-year power tariff of 2.79 cents; a price much below PDB's own power generation rate, and one of the lowest rates in the world. The Meghnaghat project came into operation from October 2002, eight months ahead of schedule. Success Case Study II: The Power Cell floated the tender for the 360 mw Haripur project in early 1997. Through competitive bidding, US company AES again won the bid by offering a levelized power tariff of 2.72 cents. The Power Cell dealt with this project without much trouble because there was no issue of free electricity like that of the Meghnaghat scheme. Plus, there was no corruption regarding the land site development. This Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) and other agreements of this project were signed in late 1998, and the site was inaugurated on May 1999. By May 2001, the Haripur plant started partial power production, and went into full production later that year. This scheme gave the country the cheapest ever power. Era of Private Power In the next five years, the government repeatedly demonstrated that whatever power project it would pursue would only go to the parties which are either close to the ruling party, or have paid a handsome bribe to a certain young but very powerful politician. As a result, the government failed to deliver in the sector. The new government came in the context of a good power supply scenario where demand and supply had little gap. The previous government had left the country with the following projects: * AES Meghnaghat 450 mw (commissioned in October 2002) This comfortable situation apparently made the government so relaxed that it forgot that demand was sharply rising every year, and that efforts to increase power generation should be a continuous process. Instead, the government succumbed to the ploys of a section of unscrupulous bureaucrats and experts, and an emerging young leader of the ruling party, who started taking hefty "commissions" for project approval.

Within 100 days of coming to power, the new government published a white paper on the corruption of the immediate past Awami League government. Consequently it suspended all power project related activities. Then the government floated the second re-tender for the 80 mw Tongi peaking power plant project to be financed by PDB. An unfit Chinese company named Harbin was chosen as the lowest bidder as it was being backed by the young politician. The company was supposed to install and commission the plant in 2004 -- but brought it online on test in May 2005, and started commercial operations in September. However, the Tongi plant turned out to be a grossly flawed project. The plant is highly unreliable and it tripped more than 75 times between May 2005 and May 2006. Internal investigations revealed, literally, hundreds of flaws in the machinery and sub-standard equipment. The Tongi plant is the only project the BNP-led alliance government could present to the country during its five year regime. Initially perceiving the Tongi plant deal as a grand success the young leader of the alternative powerhouse of the government intervened with all other power projects in the pipeline and started awarding power projects on the basis of the political affiliation of the contractors or their ability to offer "commissions." For instance, the government abruptly cancelled the Sirajganj 450 mw private power bid in early 2004. The bid was being awarded to the local Summit Power group that was previously involved with the KPCL 114 mw barge-mount power project. The Summit bid was approved by the cabinet's purchase committee, and the company had ensured finances from the Asian Development Bank and the World Bank when the Prime Minister's Office (PMO) arbitrarily cancelled the bid. The reason for this cancellation is that the chief of the Summit group is the brother of a parliamentarian in the opposition. If the bid had been okayed, this plant would have started partial power generation from 2006. Instead, the government went ahead and awarded two other public sector power projects to Harbin, violating various rules and regulations. The physical works of these plants could not start till August. The other public sector power project is the 250 mw coal-fired power plant in Barapukuria at an inflated cost of 260 million dollars under a Chinese supplier's credit. The beneficiary of this project, which has been over-priced by at least $100 million, is the brother of a 4-party alliance MP. In private power, the government awarded the Meghnaghat-2 450 mw power project to Orion-Belhasa consortium in severe violation of rules and regulation. The government was also busy bending rules to award the Meghnaghat-3 450 mw power project to an inexperienced and unknown consortium named Cadogan-Manning on the basis of unsolicited negotiation. Other than these bids, the government allowed the Rural Power Company Ltd (RPCL) -- a company of the Rural Electrification Board (REB) with shares held by various rural power cooperatives -- to install a 70 mw third phase combined cycle power plant in Mymensingh at a staggering cost of $120 million. In contrast, the PDB Shahjibazar 70 mw plant in the late nineties required only $30 million, and the 450 mw AES Meghnaghat plant needed less than $200 million (minus the cost of various supporting infrastructure needed for the first phase of the plant there). In public forums, the state minister for power spoke against private power saying that it was "draining out" money from the country. The six private power units were annually charging the nation Tk 2,000 crore for power supply. Of them, the KPCL in Khulna operates on subsidized petroleum. This subsidy cost Tk 50 crore to 60 crore a month. However, minus the oil-fired plant, the price of power from the remaining plants -- which includes two barge-mount units -- was lower or even with the average power cost of the PDB.

On an average, the price of IPP power stands at Tk 2.4 per kilowatt hour. A World Bank study in 2001 pointed out that load-shedding of that time robbed the nation of half a percent of GDP. In other words, the price of not having the electricity is much higher than the price paid to the IPPs. Finally, in 2005, the government started realizing that all was not well in the power sector. Though such realization should have put the highest emphasis on undertaking the right projects through a fair process, the government continued to allow the vested interest groups to dominate decisions. This becomes evident from the late 2005 bid to award as many as 45 skid-mount and barge-mount power projects in 45 areas of the country. This was a mindless plan that came out of the PMO -- not the PDB or the power ministry -- as skid or barge-mount plants are costlier, and setting up 45 plants require setting up 45 costly power and gas inter-connections at the plant sites. The actual objective of this scheme was awarding projects to different 4-party alliance MPs and party loyalists -- not to address the country's power problem. But this scheme crash-landed in the same way the crash program of 2000 fell flat under severe donor objection. Ultimately, the government settled for awarding only three projects totaling 150 mw capacity -- all of which went to party loyalists, not genuine power builders. These projects are still pending with the power ministry. While the government miserably failed in power generation sector due to corruption, it however opted for another wrong decision to expand rural electrification network under the REB at an unbelievable pace. This move was driven partially by the greed of electricity pole sellers, and partially by ruling party MPs trying to impress their constituency without giving actual substance. As a result, REB's power demand in four years grew to 2000 mw -- which is double its 2001 demand. The 2001 consumer base of 1.5 crore increased to 3 crore. Against such a high demand, the government could supply only 500 mw power -- making rural consumers so angry that there had been unrest in the northern region, specially in Kansat. The unrest in Kansat left many dead, and such an incident clearly tells us how wrong the government had been in pursuing its power policy. With load-shedding level reaching an unbelievable 2,000 mw plus in early 2006, public anger against the government's handling of the power scenario led the government to change the state minister for power. In reality, the state minister for power actually did not make any decisions as the vested interest lobby had made the PMO the supreme authority in the affairs of the power sector. Such a conflict of executive powers failed to add anything positive to the power sector. The new state minister for power tried to exert his power, over-riding the PMO directives, but this only brought him into major conflict with the upper tier of the government. The presence of the vested interest quarter, or the alternative powerhouse of the government, in executive decisions is also evident from the fact that in four years the government changed eight chairmen in PDB, and eight secretaries in the power ministry. Almost all the competent experts of PDB and the Power Cell, including those who had acquired negotiation skills from the past IPPs, have left their jobs or lost their appropriate desks. They have been replaced by incompetent and inappropriate men with the mandate to tamper bids by finding out loopholes or gray areas in the policy, rules, and regulations so that projects can be awarded to incompetent parties. The power sector chronicle of 1996 to 2006 period clearly shows that corruption has been the key reason for the 2001 government's failure in the power sector, and transparency was the key reason for the 1996 government's success in the same area. Failure Case Study I: The plant tripped a total of more than 80 rounds between May 2005 and June 2006. Of this, builder's fault is attributed to 45 rounds of shutdowns for 2231 hours. The prime minister inaugurated its commercial operation on September 3, 2005 and the plant had tripped within a few hours. Due to these frequent shutdowns due to builder's faults, PDB had to swallow a loss of Tk 43 crore between May 2005 and June 2006. Other than builder's fault, the plant also suffered another 1,000 hours of shutdown due to low gas pressure, or lack of gas. The builder's faults include installation of sub-standard equipment like gas booster compressor (GBC) and gas compressor, air compressor, mist eliminator motor, gas relief valve and different types of filters etc. These faulty machinery were installed in connivance with some PDB high officials who were in charge of inspection of the machinery. PDB's internal investigation pin-pointed the corrupt officials -- but nothing has been done against them. Failure Case Study II: The PPR 2003 clearly bars any kind of unsolicited deals. Soon after the CMG submitted its proposal, the implementing authority Power Cell said that the CMG proposal was not following any process and it lacked a plan. In addition its unsolicited proposal violated the Private Power Generation Policy of Bangladesh. But as this company was backed by the young leaders of the alternative powerhouse, the Power Cell saw arbitrary removal of its competent technical director and managing director who were resisting the deal. Then the power secretary was replaced with a junior officer -- who was promoted twice on the same day -- to do this job. By August 2006, the power ministry had prepared a proposal to be submitted to the cabinet purchase committee to legitimize the unsolicited deal. CMG had never undertaken any power project before. Though the project was to be awarded to CMG, it would not have any equity in the project. As per the CMG proposal, the project would be financed 100 percent by Stone & Youngberg and Eagle Financial Group, US. Such financing violates the country's Private Sector Power Generation Policy that demands that the contractor have minimum 20 percent stake in the project. CMG offered a 20 years levelized tariff of 2.78 cents per kilowatt hour which appeared to be one cent lower than the AES Meghnaghat project. But the CMG power tariff did not include the price of gas to be consumed by the plant for power generation. The Meghnaghat-1 power tariff included the gas price. On April 25, 2005, the parliamentary standing committee on energy and power ministry asked the ministry to cancel the opaque process with CMG as it was hurting the image of the government, and to float an international tender. Interestingly, under pressure from the alternative powerhouse of the government, the standing committee in its next meeting changed its position on this matter. In May, a rights group served the government with a legal notice demanding cancellation of the process to award any contract based on the unsolicited proposal of CMG. The notice said that the private power policy clearly states that bidder pre-qualification shall be made through advertisements in the national and international press, making it evidently clear that the policy gives no scope for unsolicited bids. Power industry operators say that even if this deal is awarded to CMG, brushing aside all opposition, there is hardly any possibility of implementation of the project. Failure Case Study III: This cost is four times higher than the Shahjibazar 70 mw power plant built by PDB in 2001. The only difference between the two plants was that the Shahjibazar plant was simple cycle and the Mymensingh phase 3 plant is a combined cycle one. Even the engineering and procurement contract for the AES 450 mw plant was comparatively lower than this plant. AES spent $170 million for its plant, which is nearly seven times bigger than the $120 million dollar Mymensingh-3 plant. The construction of this project was awarded to German company Siemens. The project's consultant, Lahmeyer International Polly Power Services Limited (LIPPS), Bangladesh, originates from Germany, but its shares are entirely owned by a group of Bangladeshis led by one Captain Reza, now wanted in several cases -- including subversion -- for attempting to destroy the Mymensingh plant. When the project was awarded to Siemens, the majority shareholder of LIPPS was also the unofficial local agent of Siemens. Using undue influence and bribes, LIPPS virtually ran the RPCL board. Since LIPPS called the shots, the RPCL appointed it as consultant without holding any open tender. LIPPS had been involved in consultancy of both the previous two units of the Mymensingh plants, and were arbitrarily awarded the operation and maintenance (O&M) contract for the previous plants at an annual cost at least $6 million higher than that paid by PDB for similar jobs. As corruption reigned supreme, Captain Reza -- who kept the higher authorities and a section of the press happy for many years by regularly paying them with monthly bribe -- went out of control in 2005. He tried to acquire the government shares of RPCL by influencing the RPCL board, and the follow-up tussle with the government led to his ouster from the Mymensingh plant. Captain Reza, and the others of LIPPS, forcibly shut down the plant and damaged the properties before escaping from the site in 2005. LIPPS and its executives were sued, and all the contracts with LIPPS were terminated.

Meanwhile, Siemens failed to implement the project in December 2005, and it could not finish it in December 2006. Earlier in 2004, because of LIPPS resistance to allow German donor agency KfW to conduct an audit into the books of RPCL, the government lost 20 million Euro untied grant ear-marked for this project, and another 40 million Euro for another power project. Skid-mount and barge-mount projects These deals were signed in recent months following more than one year of controversy. Initially in 2005, the government wanted to award 45 such deals to parliamentarians, ministers, and their sons and nephews. But that bid was foiled following warnings from the World Bank. This shows that though the power scenario was grim and the government had to do something sincerely to overcome the situation, the policy-makers were all hell-bent on making deals for personal benefits. Accordingly all of the six deals went to friends and relatives of the BNP leaders. PDB had opposed signing of any of these deals, saying that the 15-year costly rental terms would force it to incur hundreds of crores loss each year. According to one calculation, PDB will incur a loss of more than Tk 3,000 crore over a 15 year period by purchasing rental power at a higher rate and selling the same at a lower rate. This analysis was based on hundreds of reports that this correspondent filed in The Daily Star from 1992. Defenders of corrupt people often strongly argue that fair practices cannot always be achieved because of hindrances posed by opposing bidders. But the truth is that when there is fair play opposing bidders do not create any hindrance. This has been proved in executing the private power schemes during the Awami League regime. It also proves that honesty is not weak as a policy, it is the most effective policy that we have ever had. Sharier Khan is City Editor, The Daily Star. |

This stalled the progress of the Mymensingh-3 project, while Captain Reza fled to Singapore to avoid arrest and trial. Instead of being punished, Reza filed an international case in Singapore and has reportedly won it -- asking Bangladesh to pay him crores for terminating his contract.

This stalled the progress of the Mymensingh-3 project, while Captain Reza fled to Singapore to avoid arrest and trial. Instead of being punished, Reza filed an international case in Singapore and has reportedly won it -- asking Bangladesh to pay him crores for terminating his contract.