Inside

|

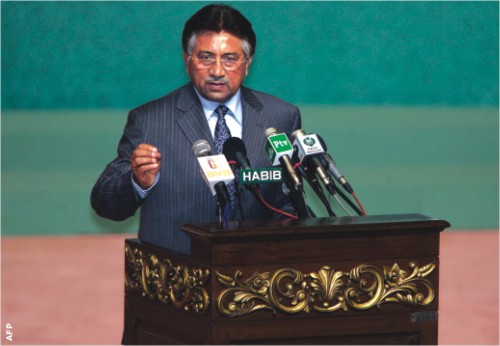

Remote control Cable TV might be Pervez Musharraf's most enduring legacy, suggests Kamila Shamsie A few days ago, in conversation with one of my compatriots, I referred to President Musharraf as "Napoleonic." She responded swiftly: "But Napoleon gave France a civil code which still exists ... I don't see our prez leaving anything positive behind." Without having to pause for thought, I countered: "Cable TV." It is one of the many ironies of Pakistan's politics that a vibrant and brave television culture is certain to be President Musharraf's greatest legacy; it is the one thing that has ensured that whatever is said about him in the history books there will have to be an admission that he brought something of great worth to Pakistan during his time in power.

Recently in The Guardian Declan Walsh claimed that Musharraf's eagerness to open up the airwaves in Pakistan was brought on by realising that a great many Pakistanis were receiving their news from Indian cable channels. There may be some truth in this, but the fact is he could have responded by blocking the Indian channels (a move which, in 2002, did come about as tensions between the two countries escalated). It is far more likely that in 1999 Musharraf recognised that, as the new leader of a nation badly in debt, with no real political value to the world (how that would change!), he couldn't be the kind of dictator his predecessor, Zia-ul-Haq had been. Dictatorship, Musharraf cannily realised, needed an image makeover. His first ever photo shoot showed him cradling his lapdogs (literal, not metaphorical) and singing the praises of Kemal Ataturk. Too much, he was apparently told. It might delight the Western media but was hardly going to have a positive response at home. That became the most talked about aspect of the first weeks of Musharraf's interaction with press -- but the more significant interaction came in his refusal to learn from the Handbook of Dictators and impose censorship. The press was free, he kept saying to a disbelieving nation -- and then he went further to say he relied on the press to alert him to his own failings. In effect, he made the press his opposition party. And so the honeymoon commenced. It's true that the press still remained wary about what it wrote and said about the army and ISI -- and those who transgressed these limits were made to suffer, sometimes violently -- but compared to Musharraf's predecessors, both civilian and military, this was a new, glorious age. Within months of Musharraf's coup, the Cable TV era had begun. Pakistan's two TV channels had always been a joke -- heaping praise on those in power, ignoring those in opposition but now there was a world of news channels: airing views from across the spectrum, questioning politicians on different sides of the political divide, holding accountable, in front of the camera, those who had never publicly been questioned in such a manner before. The whole range of Pakistan's multi-layered and contradictory identity was on display -- a click of a button could take you from 24-hour religious channels to 24-hour music video channels. A provocative cross-dressing talk show host became the country's most popular TV figure. Continuous footage from the earthquake zone in 2005 did much to compel those in the rest of Pakistan to raise money, volunteer time, collect donations.

A shame, then, that the one person most unable to view this as progress was President Musharraf himself. In place of the man who said he relied on the press to help him rule wisely there appeared a man who started insisting that to speak against him was to speak against the state. When news channels dared show footage of the overwhelming reception being given to the chief justice who Musharraf had suspended the TV stations were threatened, taken temporarily off air, and physically attacked. Through this they kept their cameras rolling. Just as they kept their cameras rolling in May as news programs kept cutting from one live broadcast to another: images of people lying dead in the streets of Karachi to images of Musharraf, concurrently, dancing on stage in Islamabad. It made you understand how Nero's fiddling would have looked on CNN. It's possible, I suppose, that some might conclude from all this that Musharraf was a fool to open up the airwaves. But as I said before, it is his only worthwhile legacy -- and a man such as Musharraf must care deeply about legacies. His failure, of course, was not in the freedom he gave the press but in his unwillingness to see how that could work to his advantage. If he had stayed true to his original word and allowed the press to be his conscience, his opposition party, his barometer of the nation's mood -- he would not be sitting quite so precariously now. Kamila Shamsie is an eminent Pakistani author and columnist.

|