Inside

|

Entry strategies Jyoti Rahman and Syeed Ahamed discuss options for the next political government In his article "Exit strategies: Some lessons from history" in the August edition of Forum, Professor Rehman Sobhan noted: "The exit strategy for the caretaker government (CTG) may turn out to be its most challenging task." Eventually, each exit creates the opportunity for an entry as well. As the current non-political government exits, a political government will enter. The entry strategies of different factions vying for power after the current government exits may well turn out be the most important determinants of the course the nation's politics will take for years to come. Professor Sobhan drew lessons from the exit of previous militarised regimes in Pakistan and Bangladesh. We look at possible lessons that can be drawn from the entry strategies of political factions in the aftermath of those military interventions.

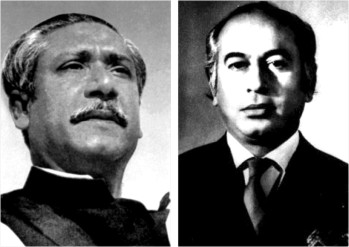

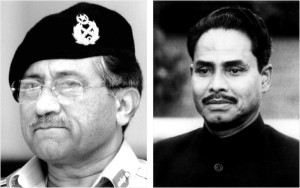

Politics past Ayub Khan banned a number of stalwarts from participating in any election. Indeed, the regime tried to ban party politics altogether as electoral democracy was dubbed "unsuitable to the genius of our people." Politics, however, did not stop. Ayub shed his uniform and decided to become a politician himself, forming a King's party. An opposition alliance sprang up to take Ayub on within the confines of his "basic democracy." As the opposition alliance broke up because of inherent differences on regional autonomy, the New Politics of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and Z. A. Bhutto arose by the late 1960s. They led a revolution that toppled Ayub. The successor regime allowed elections, where Mujib and Bhutto received public mandates for their respective politics.The old Pakistan ceased to exist in the bloodbath and battlefields. The new states that replaced it were based on the respective New Politics. However, within a few years, both Mujib and Bhutto were killed following military interventions. Coincidentally, at the helms of successor militarised regimes in both Pakistan and Bangladesh were generals named Zia. Both Zias, like Ayub before them, promised to create their own New Politics. But the means they used, and the results they achieved, differed markedly. Zia-ul-Huq followed the Ayub prescription of banning party politics before creating a King's party. Zia-ur-Rahman, on the other hand, allowed party politics to flourish. The opposition reactions to the Zias also differed. In Pakistan, the opposition shunned the regime. In Bangladesh, the opposition participated in elections and accorded the regime political legitimacy. The regimes, and lives, of both Zias ended violently. In each case, elections ensued. In each case, eventually the army intervened again to sweep away the Old Politics. In Bangladesh, the political interregnum was very short -- barely ten months. In Pakistan, politics was allowed to persist for eleven years, but the army continued to run security and foreign policies, and regularly deposed successive elected governments. Both H. M. Ershad and Pervez Musharraf accepted the inevitability of party politics, and each created his own King's party. Both faced opposition, but the opposition parties proved to be equivocal and disunited. Some participated in elections under the regimes, but others remained steadfast in shunning the generals. Ershad, the Bangladeshi general, was relatively more tolerant of the opposition. Following Ayub, Pakistan's Musharraf, on the other hand, has barred popular politicians from running against him. Ershad's regime ended with politics triumphant -- the same politics he tried to sweep away. At the time of writing, the last act of Musharraf's rule was yet to play out. A few entry strategies of politics become apparent when we look at the history. First, the generals themselves wanted to enter politics, initially in uniform, and then as politicians. All generals entering politics created a King's party. The very creations of such King's parties continued junta hegemony and damaged the fabric of politics, as Professor Sobhan argued: "To depend on elements who cannot politically sustain themselves and can only be elected through patronage from the cantonment will take Bangladesh down the same road of corruption and malgovernance which proved the undoing of previous military-backed regimes." It is historically evident that politicians have always replaced the King's party. However, the strategies used by politicians in their engagement with the King's party have differed. Some politicians adopted the strategy of offering a New Politics. Mujib and Bhutto, for example, didn't seek to replace Ayub with the politics of the 1950s -- the former championed an independent Bangladesh, the latter promised a populist mix of Islam and socialism. And neither were new politicians -- Mujib had been active in politics since before partition, and Bhutto's political apprenticeship was under Ayub. That is, old politicians can also create New Politics. Of course, a strategy is needed to resolve any potential conflict. One strategy, available only to the regime, is to allow a free and fair election open to everyone's participation -- the first step towards democracy. Mujib and Bhutto adopted the strategy of principled refusal. They defied Ayub's basic democracy. Ayub incarcerated them, but eventually it was his regime that fell. Closer to our own time, Begum Zia during the 1980s refused to take part in any election under Ershad, and reaped handsome political rewards by winning the general election in 1991. However, not all refuseniks were as successful. Leftist factions that shunned electoral politics after the fall of Ayub became marginalised. And not all refusals have been principled. Some refused to participate out of mistrust of their rivals, while others wanted to resume Old Politics.Further, steadfast refusal did not always end military rule. For example, the opposition's refusal didn't end Zia-ul-Huq's brutal regime. And the more prolonged the militarised regime is, the worse damage it does to the country's future democracy, and the harder it is to clean up the mess it leaves behind. It is understandable why politicians might prefer Old Politics. Genuinely new politics are rarities, even in mature democracies. This is why the New Deal and Thatcherism do not happen after every election. So, it is perhaps too much to expect all political factions opposing militarised regimes to produce New Politics. The strategy often adopted when becoming a refusenik involved risking marginalisation, or the cost to the nation of such refusal was very high, or if there was nothing genuinely new to offer, has been to participate. When successful, this strategy has resulted in a relatively peaceful transition to electoral politics. However, politicians adopting this strategy risked being accused of flip-flopping and selling out.

Choices We hope that the history will not repeat itself -- there will be no King's party, and turn-coats waiting to join one will be disappointed. That is, we hope that in the wake of its exit strategy, the current government will not create a condition that requires politicians to adopt a strategy of refusal. And we fear what might follow a refusal strategy based on mistrust and Old Politics -- violence, social dislocation, economic instability, foreign meddling, and worse. Instead, we want the government to keep its promise of a genuinely free and fair election where anyone can participate. And we want to see our political parties, in collaboration with an independent Election Commission, regenerate themselves. We look forward to a politics divorced from black money and hired thugs. That is, we want to see the politicians adopting the entry strategy of New Politics. And the most successful proponent of New Politics in our history defied the limits imposed by successive militarised regimes and led to the creation of Bangladesh. That is, limits imposed by the government are not, in and of themselves, impediments to the emergence of a new politics. However, if this does not happen, then what? If there is a King's party, or if the politicians adopt the refusal strategy, or a combination of the two, then the future does not look nearly so bright. |