Inside

|

What does the opposition want to oppose? Farid Bakht exhorts the nation to think seriously about the future For a few days this monsoon, members of the long-term caretaker administration were worried. Their plans looked like they might go up in smoke. Several thousand arrests later, they regained their poise. It seems every three months, they come a cropper (the first being the botched "voluntary" expulsion of the Two). While it lasted, the streets belonged to the students and slum dwellers. They were the vanguard but there was nothing following behind. Were the lower middle class in Dhaka and Chittagong, the small town (mofussil) traders and professionals, and finally the farmers and landless labourers engaged in significant numbers? Perhaps if the situation had continued, they might have joined and then it would really have been difficult for the administration. We got a glimpse of a part of the opposition, minus not just the Two Ladies but minus the political parties too. This was not to be 1990. Political definitions

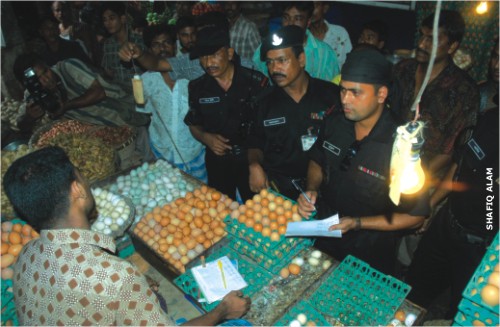

Those who dislike not living in the form of democracy we have had since 1991 have generally restricted their opposition to what I would call "limited political rights." This includes human rights, the rule of law, and a call for a return to representative democracy.What they are being offered instead appears to be the dismemberment of the three main parties (Bangladesh Nationalist Party, Awami League, and Jatiyo Party). This is being done via a process of reform and a clampdown on activities. The raison d'etre of the big two parties (at least for the last quarter century), in the shape of the wife and the daughter of former leaders, is in danger of being removed. In parallel to electoral reform, would you bet against constitutional changes with, perhaps, wider presidential powers? I suspect many politicians will be more than happy to support constitutional changes in return for their last bite at power -- they are all getting on, after all. Free and fair elections could then be held, without the dynasties, and the army would return to barracks. Foreign media (and investors) would hail this as a sign of democratic maturity in an important "moderate Islamic nation." Would the political parties and allied civil society individuals then feel they had achieved victory? Maybe. Maybe not. However, what would the result be? B. Chowdhury or Mannan Bhuiyan leading a rightist BNP alliance government? Tofail Ahmed and the other elderly Awami Leaguers claiming the true "secular" legacy of Sheikh Mujib and then ruling like any other rightist? A month after this election, what would go through the minds of the farmers and the landless labourers? Would they be optimistic about their future, having seen the clock turn back to 1991? Would small traders and lower middle class professionals believe their quality of life, or survival, would be ensured once the politicos were back at the helm? Limited ambitions So why is it we do not move beyond the issue of limited political rights? We could remind ourselves that many groups are content to see civil society restrict debate within these confines. Let me name a few: The World Bank, the IMF, most (not all) of the donor agencies, many Bengali beneficiaries of these agencies, "democracy NGOs," and of course the robber baron politicians. All during 2001 and 2006, the Awami League and their alliance partners campaigned on the same issue: vote rigging in 2001 and expected rigging in 2007. They had no interest in mobilising the country on economic rights. Their "programs" were merely one line promises, drawn up by economists who were never going to be allowed to implement a real program of change. The BNP did the same during their period of opposition from 1996 to 2001. The events of August showed everyone that there is some sense of frustration and that people's patience is not eternal. They cannot be rewarded with the usual betrayal by politicos and many civil society leaders. Ordinary people know that much of "civil society" is bankrupt in terms of vision or aspiration. They also want to see much more than what has been dished out by this administration. Yes, everyone wants uninterrupted electric power but that hardly makes for a program. Yes, everyone wants to see a reverse in spiraling food prices, but let us see some honesty from the technocrats. In reality, the farmer is selling at absurdly low prices while consumers are over-paying. The farmer cannot get the level of government subsidy he deserves. Subsidising poor farmers (unlike rich farmers in rich countries) is anathema to the IMF and World Bank. While we need to reduce food prices in the markets, we need to, in parallel, think about the producers and come up with solutions for both producer and consumer, rural and urban.Instead, with very little financial resource going to the farmer and rural sector, and no new thinking, the administration sends security personnel to discipline the market traders. That is more in tune with management in a command economy.

The technocrats' objective is to reduce urban food prices in order to keep a lid on urban political protest. They do not give a damn about the farmers because they do not consider them a political threat. This is not a policy for national economic development. Historic decisions Therefore, if people want to oppose, I believe they must first work out what they want to oppose. If they want a re-run of 1990, then they will replace this current administration with another Khaleda Zia. If that is the limit of their ambition, they should dis-engage. 1990 is held up as a historic victory. For me, 1990 was a missed historic opportunity and at best a partial victory. Replacing General Ershad's Pajero with Queen Khaleda's Mercedes Benz was not enough of an achievement. Civil society was right to struggle for limited political rights but they could have gone for much more. If there is a next time, I hope they raise the bar. They should decide to do more than change a regime and instead aim to change history. The wrong target? Asian military interventions come in many guises. The Pakistani model is only one of them and a disastrous one at that. If the army allows the so-called technocrats to destroy huge swathes of the economy, the people will eventually hold them responsible. Perhaps the powers that be might want to get in touch with their East Asian counterparts and find out how economic nationalism works. They could learn about how farmers and industrial development went hand in hand, in defiance of IMF/World Bank prescriptions. I do not think many will, since years of training in US academies may have closed that line of enquiry. I do have confidence that one or two might though. Not all will be pleased at the economic direction with its surrender to foreign interests.

The army has rebuilt its reputation over the last decade and a half, primarily through its UN missions outside the country and disaster management efforts inside the country. Unfortunately, it now runs the risk that it might lose its hard won respectability if, even unwittingly, it allows the wrong type of technocrats to run the economy. The civil opposition might also want to change course. Instead of taking the army on, it might better focus its opposition on the economic mismanagement of the caretaker administration and mobilise people on an alternative economic program. That would mean the target is not the army as an institution, but the technocrats and their policies. I am assuming that mainstream politicians will do nothing of the sort. The space is therefore open for new movements and a new opposition. Ironically, that space has been created by the actions of the past few months. As they say, you do not always get the outcome you plan for. Farid Bakht is a freelance writer and businessman. |