Inside

|

Informed Choice Access to information is the key to good elections, argues Shayan S. Khan

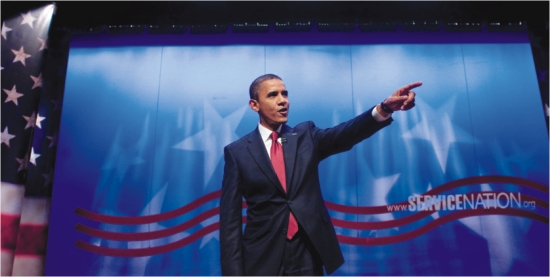

Bangladesh's return to democracy is much anticipated, and an obvious cause for much speculation. The recent dilly-dallying about our date with that destiny we are so eager to meet has finally settled for the fag end of December. Who does not wonder what it holds for us? Can it awaken us to a different conscience? Will it ring the bells of change that is positive, egalitarian, and progressive? Or will it be a mere instrument to revert back to that model of society unique to us from 1991 to 2006 (which, if one may be so crude, was nothing more than a bastardisation of the concept of democracy)? What is the change that we seek anyway? Leave no room for doubt, that each and every Bangladeshi, whether individually or as part of a group, party or social circle exerts concern over his or her country's future. But our singular failure as a people over the last two years has been in defining, consensually, what we want, expect, and can entrust to our government. So as December 29 approaches, is there any indication of a better class of politicians, a better conduct of politics, on the horizon? If there is, I certainly have not seen it. It could not have been expected, of course. Two years is a timeframe for quitting cigarettes. Not for cleansing a nation's political structure. And so, for better or worse, we are set to vote again for the same old faces, engage in the same old vices, and then swear at the same broken promises. But two years cannot be erased from the course of a nation's journey just like that. This time, we must make our politicians take the mandate we hand them seriously. For 15 years, through three elections, they were able to ignore it and pursue their own personal agendas, smug in the knowledge that they could. The vast majority of the Bangladeshi electorate was "illiterate," and by association, "ignorant." What could they ever know? Their votes were to be bought, if not coerced. The irony need not be mentioned. Literacy rates continue to remain low, but I still retain the faith that the end of the charade parading as democracy on 1/11 held potential for good. Even if, for a moment, it must have caused Bangladeshis from Tetulia to Teknaf to pause and think at some point over the last two years. Seven years is a lifetime in politics. It has been a long, long time since we last saw a ballot box. Apparently, they will be transparent this time. In terms of our progress, however, they will be redundant if they are staring back at the same old ignorance in us, the electorate. Over the next four weeks and beyond, let us strive to prove that whatever we might be, we are certainly not "ignorant." Not anymore. We have just witnessed what has been described as a transform-ational election in the United States. The scope does not exist for us to take such a large step at this point, but over the next four weeks, let us strive to make our forthcoming verdict at least significant. I firmly believe that, as a nation, our greatest strength lies in our collective resilience. The vast majority of this resilience derives from the likes of the people living in the low-lying areas, our brave farmers, the entrepreneurial village-women. The people who read magazines such as this, or write in them, or publish them, contribute very little. We don't have to – we face very little by way of danger to our lives or subsistence on a daily basis. We usually live in the cities, in brick houses no cyclone can bring down, and often on plots of land our forefathers have secured for us. We are insulated from the conditions that build resilience. But we are well-positioned to contribute other strengths. One, in particular, has particular relevance to the upcoming election. You have in your hands today access to the full list of candidates submitted to the Election Commission. You only have to care enough to look. Once the Commission has approved the selection of the candidates, on December 7, you will have access to the full list of candidates whose names will be on ballot papers all over the country come the 28th. You need only visit the Election Commission's very well-maintained website. An admittedly long list, but you will probably not bother with too many beyond your own constituency, except for those in strategically important places like Dhaka, or those that interest you for some reason or the other. Then, unless your mind is already made up, you might just care enough to gather information on the candidates for your constituency. The media should probably have something on them in the weeks leading up to the election, but if you're in Dhaka, why not pay the commission a visit? They will have what you need, just get a copy. Then, for hypothesis' sake, let us assume you are registered in a constituency with only three candidates. One has a charge of murder against his name, another has a history of corruption, and the third did not sit for his SSC exams. You choose whichever is the lesser of the three evils to you (or if so inclined, even the greater if you wish) and then go on to cast your vote accordingly. You knew who your choices were, you gathered the information necessary to compare between them and then you chose the person you want to represent you. Without much effort at all really, you have just negated for yourself one of the imperfections of democracy in developing countries: The choices people make are not always informed. There are various reasons for this, and some are even acceptable and prevalent in mature democracies. For example, a person may not care to know. He or she has every right to turn up at the voting booth on Election Day with the weather that morning as the deciding factor. Another may not have the mental capacity to discern between a murderer and a saint, but that can never be reason enough to discount his or her vote. And then, of course, there are the bigots and the bases, who will happily vote for the devil as long as he is disguised in their party's colours. What is unacceptable is when perfectly straight-thinking individuals – who would vote differently if they only knew better – enter their booths and are presented with a list of names they know next-to-nothing about from independent sources. They took an interest in the elections; they would have liked to know more. Some have attended a few rallies on their way home from a hard day's work in the field and heard promises of schools and bridges. Some have asked probing questions when visited by campaigners, and learned everything but the truth. Some, valuing independent opinion, have gone to the village elders. They have returned even more confused, not only about the upcoming election, but also about 1971.

Bereft of the access to information we have, they cannot be said to have chosen. Rather, a choice has been imposed on them, or at best, they have somehow arrived at one. Unless unusually perceptive, the kind to tell a man to be trusted from the look in his eyes is usually misinformed. One wonders what portion of our over-8 crore registered voters may fall in this tragic category on the 28th. Quite a chunk, probably, given our large rural population. And they are not at all absent from our urban centres either. While they are the ones who are usually more resilient, we are, more importantly than literate, informed. We have access to information, and the various mediums through which it is disseminated. The internet, newspapers, television, radio, even mobile phones are all sources of information these days and the typical reader of this magazine would have access to most, if not all of them. If nothing else, this election represents an opportunity for us to utilise this access we have to complement our resilient men and women who plough the fields and sow the seeds that feed us so that collectively, we can at least arrive at a decision that is informed. Mind you, we haven't made the choice yet. In all honesty, during the last elections in 2001, the scenario was very different. Seven years on, penetration is still relatively low, but back then, there weren't as many Bangla channels on television or radio, internet meant dial-up, and the number of mobile phone users was exponentially lower. The print media, which always maintained a presence anyway, has also upped the pace of its progress. All of it combined has resulted in a certain segment of the population that is, for the first time, in a very good position to make an informed choice without much effort. Where I hope we do make an effort is in passing on the information we receive, gather or come across to those who are not so fortunate. I hope we visit the Election Commission and gather the information for ourselves from a reliable, independent source. I hope each one of us thrives in the role of a point of dissemination. We can start slow. Pass it on to our friends. Tell them to pass it on to theirs. Then we can concentrate on our own constituency. Eventually, we may go around different parts of the country carrying photocopies of the candidates' information for that constituency. Travelling around Bangladesh in winter is an amazing experience anyway. Stop random strangers on the street and ask if they're from the constituency. If they are, and show a genuine interest in the election, hand them a copy of the candidates' information. If they say they can't read, talk to them. Be objective. Be nothing more than a voluntary source of information. It is not the type of thing one can do alone. A few like-minded individuals working in small groups would be ideal. But as I write, I realise that it is not the type of thing that can be seen as work. Don't have numbers in your head. Even if its only your nearest cha-wala or a very impressionable young cab driver you manage to help make an informed choice, be proud. Do it all in the spirit of sharing. I mentioned earlier how America had just witnessed a transforma-tional election. It was truly transfor-mational because a transfor-mational figure, Barack Obama, was swept to victory by a transfor-mational electorate, the Americans with eight years of George W. Bush behind them. It's not as if they come along often anyway, but there is certainly no prospective transformational figure in the political scene in Bangladesh today. But an electorate taking its first steps towards informed decision-making would be a very significant juncture in the course of our politics. Obama's victory went to show how a strong grass-roots movement allied with an astute sense of how to utilise technology can create an unstoppable force. It would not be quite applicable here yet, but the grassroots-technology combination is the future of political campaigns. To whatever extent I have proposed it here, it has obviously not been in favour of any political party, but altogether a rather more important cause. It is inevitable that millions of voters will be voting without actually knowing anything about their candidate in our upcoming election. Many of them, if they knew, would not side with anyone involved in murder. But unknowingly, many will. Some of these votes can be saved if people who do know make sure they just talk to people over the course of this month.

Eventually, as we move from informing voters to actual informed voting, which may take many years still, this may hopefully produce the better class of politician that we seek. Politicians who know they haven't bought their votes – the people have chosen them. They haven't forced people to vote for them – the people put their faith in them. Politicians who know they must conduct themselves in an informed way, for they are the informed choice, of an informed people. Shayan S. Khan is Operations Manager, CSR Centre.

|