Inside

|

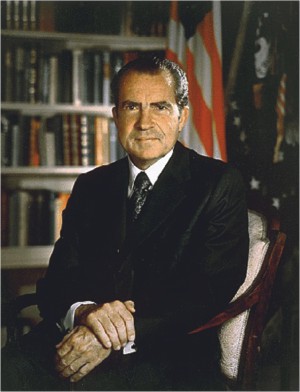

Nixon's demons In this exclusive extract from his forthcoming book, F.S. Aijazuddin explores the reasons behind the ill-fated US tilt towards Pakistan before and during Bangladesh's Liberation War

To modern historians, these papers and the extracts of minutes of the Senior Review Group and its successor the Washington Special Action Group have an interest because they serve, not only as examples of the examination that South Asian issues were subjected to within the highest echelons of Nixon's administration, but also of the polarization that gradually crystallized within that administration. Regardless of what positions they might take, no one in the US government could argue about what the issues were. They were self-evident: How should the US balance its policy towards the two South Asian countries that both wanted to be friends of the United States and yet remain inimical to each other? Could the US be even-handed and sustain a parity in its relations with two unequal nations? Should it be prepared to act in the event of their internecine conflicts as a reluctant referee? Could the US government benefit from the lucrative supply of arms to both India and to Pakistan, without watching them use those very weapons against each other? How could they be tempted away from their pro-Soviet and pro-Chinese leanings, and could Pakistan's closeness to Communist China be used by US to its own benefit? Should the US the world's most powerful democracy support the elected leader of the world's most populous one, or tilt towards Pakistan without seeming to support its authoritarian regime? The schism between the two countries found a mirror image in the divide that emerged within Nixon's administration on the preferred approach to these issues. It separate those who advocated catholic orthodoxy (i.e. the State Department) from those who favoured experiment and innovation (Kissinger, at the behest of Nixon). Nixon remained suspicious of the State Department specialists on South Asia whom he regarded as "pro-India." Kissinger complained to Joseph Farland (Oehlert's successor as US ambassador to Pakistan) that: "State is driving me to tears." The situation worsened as the crisis in South Asia degenerated by the end of 1971 into open war between India and Pakistan over East Pakistan/Bangladesh. During the thick of it, Nixon and Kissinger talked in the Oval Office, and when Nixon asked whether the State Department had lodged the protest he had instructed it to make, Kissinger could not resist griping that "the State Department did not promptly or effectively carry out White House instructions." Even George Bush (then US ambassador to the UN) reported that during a meeting on December 10, 1971 with Huang Hua, the Chinese representative to the UN in New York: "Henry makes very clear to Huang that he has complications at the State Department. The State Department to him is an increasing obsession. He is absolutely obsessed by the idea that they are incompetent and can't get the job done. It comes out all the time." The schism that disturbed the pedantic lawyer in Secretary of State Rogers and so exasperated the power-centric Kissinger in the White House emanated from the Oval Office itself, from deep within the tortuous crevasses of President Nixon's own mind. No-one -- including Nixon himself-understood entirely the motives that underpinned his actions. He buried rather than cremated his prejudices, thereby allowing them to resurrect themselves at some future time. He had strong likes and dislikes, despising those weaker then him, admiring those who stood up to him, and fearing those who were most like him, like, for example, Mrs. Indira Gandhi. Unconsciously, perhaps, Nixon saw a parallel between his own political career and that of Mrs. Gandhi. He too had struggled for political survival against a condescending Establishment, and while he stood in awe of her tenacity and her fierce patriotism, he found it more difficult to accept her equally militant nationalism. They had met before during his earlier visits to India, but during their meeting on August 1, 1969, Mrs. Gandhi mentioned how happy she felt that Nixon stopped in New Delhi, adding that: "[Our] talks have helped me know you better." Nixon responded with reciprocal insincerity by mentioning that they had met before but on this occasion they had a "rare opportunity" for "three hours of good talk." As the East Pakistan crisis deepened, with every letter that Nixon sent to Mrs Gandhi, he must have recalled her parting words in August 1969 that at no time had India wanted to create difficulties for the United States. Indian history, she said loftily, conditions India's views, and the Indians did not want the US to do anything that would damage its interests. When writing to her in May 1971, he humoured her by acknowledging that "as one of Asia's major powers, India has a special responsibility for maintaining peace and stability in the region." Privately, he described Indians as "a slippery, treacherous people [...] and not to be trusted. Kissinger agreed, calling them "insufferably arrogant." And again a month later, on August 11, summoning the Senior Review Group to his office, President Nixon told them: "Now let me be very blunt." He mentioned that he had been going to India since 1953. "Every ambassador who goes to India falls in love with India. Some have the same experience in Pakistan though not as many because the Pakistanis are a different breed. The Pakistanis are straightforward and sometimes extremely stupid. The Indians are more devious, sometimes so smart that we fall for their line." If the number of visits Nixon made to any country was any measure of his interest in it, then the five visits he made to Pakistan compared to the three he made to India revealed the bias he developed towards Pakistan, its "straightforward [and] stupid" Pakistanis, and their leader Yahya Khan. After Nixon's meeting with Yahya Khan at Lahore, Bob Haldeman (then assistant to the president) scribbled in his diary that Yahya had made a strong impression on Nixon as "a real leader -- intelligent -- and with great insight into Russia-China relations." Haldeman added that Nixon felt that Yahya could be "a valuable channel to China esp -- but also to USSR." Nixon was to modify his opinion of Yahya Khan during the course of the next few years, but his commitment to the man never wavered. Kissinger, like many others in the US and even more in India, could not understand Nixon's loyalty to Yahya Khan. While Kissinger told visiting Pakistanis about his president's "high regard for President Yahya and a feeling of personal affection for him, he confided to the US ambassador to India, Kenneth Keating: "In all honesty ... the president has a special feeling for President Yahya. One cannot make a policy on that basis, but it is a fact of life." A policy was in fact fabricated on that flimsy premise together by Kissinger and by Nixon, a policy that would in time bring two distant adversaries -- the United States and the People's Republic of China -- closer to each other, and that would drive the two neighbouring countries in South Asia -- India and Pakistan -- even further apart. "It all first stared when in July 1969 Nixon visited Pakistan for day," Yahya Khan recalled afterwards in the deposition he sent to the Justice Hamood-ur-Rehman Commission. "It took me two full years of hard laborious efforts to bring these two mighty powers to the point of talking to each other. These two nations have shown such gratitude to us that I cannot really describe. Why I say all this is because it was mainly due to this reason that both countries gave us political and diplomatic support in spite of American press, the Senate and the Congress being so hostile to us. Unfortunately, this support was not enough in the face of Russia's open support to India, but then I could not drive them any more." F.S. Aijazuddin is an eminent Pakistani scholar and editor. The above is an exclusive extract from the manuscript of his forthcoming book: The Tilt that Failed: US Policy During the 1971 War in South Asia. |