Inside

|

Modhupur Text by Tasneem Khalil Photos by Amirul Rajiv

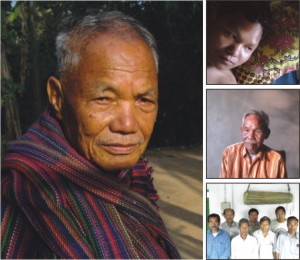

Here goes an open invitation: come and see the game, visit one of the most attractive zoos in Bangladesh, spread over 478 square kilometres of land that is home to the largest sal forest in the world. On display: more than 25,000 Mandi and Koch adivasis. Welcome to Modhupur, best described by an independent observer as: "An open laboratory where the adivasis are the guinea pigs suffering endless experimentations at the hands of the forest department, multi-national corporations and their guardian institutions, the church, Bengali settlers, and the department of defense." For us I and photographer Amirul Rajiv it was pretty much of a shock and awe experience to take endless motorbike rides deep through the sal forest. For two days and nights we raced from one village to another, documenting the lives of the people whose woe we were investigating, the extent of their suffering, the ruthless oppression they have to endure, the mindless rape of their motherland which they so dearly refer to as ha.bima.

And then, this is the story of resistance, how the Mandi adivasis, persecuted for hundreds of years at the hands of civilization are now resisting and trying to turn things back, to desperately make their voices heard by an uncaring country. It all started with the forest department taking over "conservatory" duties in Modhupur in 1951. In 1955 the area was declared as "restricted forest." In 1962, declaration of a "national park" came in. What exactly happens when the ownership of a sal forest is forcefully taken away (without any consultation) from the very people -- Mandi and Koch adivasis who worship it as their motherland, and is handed over to a union of corrupt guardians at the forest department? Reverend Eugene E. Homrich, pastor at Saint Paul's Church, Pirgacha, Modhupur has a quick answer: "Wherever the forest department is, there is no forest."

And the people? Well, they became easy target practice for the forest guards and victims of a thousand false poaching cases every year. Indiscriminate shooting at Mandi people in Modhupur is a regular affair. Ask Sicilia Snal who was collecting firewood on August 21, 2006. Without warning forest guards, five or six of them, opened fire on three Mandi women around 7.30 in the morning. Sicilia was injured with hundreds of shards of cartridge piercing her back. Her kidneys were badly damaged. One of the worst victims of oppression in Modhupur, Sicilia cannot walk or move her hands properly. "Looks like the forest department is competing to win a gold medal in shooting," Pavel Partha, environmentalist and human rights activist best known for his authoritative work on Modhupur, commented to us.

"They came here, the forest department, and served us with an eviction notice," Jerome Hagidakh, an octogenarian Mandi leader, described how it started in 1962. "The government has handed over this forest to us, we were told. The Mandi people will be uprooted and we will plant trees instead." This is "development" ADB (Asian Development Bank) style: finance projects that destroy thousand year old natural sal forest and plant exotic species, all in the name of preserving the ecology of Modhupur.

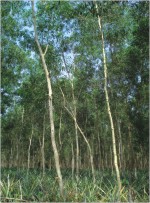

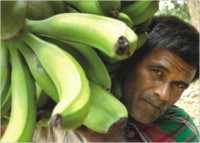

However, good guys in ADB and their angel friends in the forest department and Ministry of Environment did not stop there. And "social forestry," another model for destroying bio-diversity, was imported to Modhupur. Now, again, thousands of acres of sal forest had to be wiped out to make way for eucalyptus, acacia, and manzium plantation: all exotic species threatening to local ecology. Plus, hybrid, genetically engineered banana and pineapple. "So called social forestry has destroyed bio-diversity in Modhupur and has crippled the Mandi people's livelihood," according to Pavel Partha.

Multi-national corporations like Syngenta, Bayer, ACI, Auto Equipment, and Agrovet have made sure that poisons -- labeled "Toxic: Do not inhale, eat or touch with bare hand" -- make their way to our tables through hybrid banana production in Modhupur. Every year, four to five Mandi workers, mostly women, die of poisoning at these plantations, Eugene E Homrich estimated. "We don't eat these bananas ourselves. How can one risk eating something cultivated with so much insecticide and injected with so much chemical hormones," Anthony Mansang, a Mandi activist, told us. "Mandi people had their own type of agriculture entirely dependent on the natural sal forest. That was their livelihood. Now that the forest is quickly vanishing and genetically engineered banana has been imported, toxic insecticide and hormones have poisoned Modhupur and its people. Now the only option they are left with is to work as cheap labours at these plantations," Pavel Partha noted.

This is Rasulpur Firing Range. A classified (by that count much information is not available except two or three sentences here and there plus a satellite shot at Google Earth) military installation buried deep inside (we had to smuggle ourselves in, risking getting shot) the Modhupur forest. Target practice for Bangladesh Air Force resulted in the eviction of two Mandi villages and loss of more than 500 acres of sal forest. Air-to-ground bombing practice, that is a routine affair, has scared off wildlife from the area and killed a few Mandi bystanders in recent times. "So defense means wiping out the sal forest and bombing life out of it. How's that? We don't understand why they could not go and do as much as bombing as needed in the Bay of Bengal," a Mandi schoolteacher (name withheld on request) questioned. "They came from America, England, Europe and took away our religion," Jonik Nokrek described the background of how Christian missionaries first came to Modhupur and carried out large-scale conversions of the Mandi people. Within 50 years since the first church in Modhupur was built most of the adivasis were lured or forced into converting to Christianity. Today, 85% of the Mandi and Koch adivasis are Christians and only 242 elderly Mandis follow the original Mandi religion, according to Eugene E. Homrich's estimate. The church provides the people with much-needed education and health facilities that have contributed immensely to the development in Modhupur. However, as one Mandi cultural activist (name withheld on request as speaking up against the church is socially forbidden) noted: "All of this was provided at the cost of our thousand year old culture or absolute Christianization of it."

Then came Bengali settlers and with them Islam. Though only 64 Mandis converted to Islam in recent years (according to Eugene E. Homrich's estimate) these Bengali Muslim settlers, coming from all parts of Bangladesh, are engaged in routine bullying of the Mandis in Modhupur. Rajiv was quick to note: "I never saw people wearing such long beards anywhere in Bangladesh." He was commenting on two maulanas whose beards were, in fact, reaching towards their knees. Bengali Muslim presence and their big-brotherly influence in the matriarchal Mandi society are perceived as alarming by Mandi cultural activists. "Today, our children have started taking Bengali as their first language, raising the fear that sometime soon Mandi language will become obsolete," Eugene Nokrek said. "10 years back you would not spot a woman in veil here. We are a matriarchal society and that's so alien to us," another activist chirped in. Pavel Partha told us about an unofficial government plan to engineer large-scale Bengali settlements in Modhupur clearly aimed at creating ethnic imbalance. In other words, that would make this "Chittagong Hill Tracts: Part II."

January 3, 2004 is a red date in the Mandi story of resistance. A procession, a silent march by Mandis united against eco-park and "conservation wall" was on. A few minutes into the march they were greeted with bared teeth shooting by the police and forest guards. Piren Snal, a farmer who is now the symbol of resistance for the Mandi people, died of bullet injuries while hundreds were injured. One of them, Utpal Nokrek, a young man in his twenties, had to settle down with a severed spinal cord and became bed-ridden for life. "We have learnt to receive bullets in our chests and we will resist again and again any bid to take away our motherland from us. We will protest," Utpal told us, lying down in his bed, with a piercing stare. "I will go on my wheelchair and educate people on this issue, they will listen to me, they need to know. I will coin slogans for resistance but I will never allow this evil plan to succeed, ever." Mandis are now rising up against the oppression in the name of "ecological conservation," and they are ready to face any danger, we were told. Then there is the nakmandi ancient Mandi prayer hall rebuilt after a few decades near Jonik Nokrek's home in Chunia. Jonik, a highly respected Mandi leader in his nineties, is on a mission to revive the original Mandi religion Sangsarek once more through celebrations of ancient Mandi rituals like Wanna. "I am listing the names and redrawing the images of our ancient gods," Jonik told us. "Aliens came here and took away our religion but we will hold onto it, the religion our forefathers adhered to for a thousand years." Resistance is on in Modhupur, both on the political and cultural front. And each time oppression and invasion will try hunting the Mandi and Koch people, they will refuse and fight back: that's a promise they have signed with their blood. Tasneem Khalil is a writer and editor, Forum. For more information on his investigation, please go to: www.tasneemkhalil.com. Amirul Rajiv is Photo Editor, Forum. |

This is the story of how the Bangladesh state, through its forest department, is treating one of the most colourful ethnic minorities in the country as easily dispensable burdens. This is the story of how the Asian Development Bank and its evil twin the World Bank is financing projects of mass destruction in the name of development, destroying acre after acre of sal forest. This is the story of how multi-national chemical merchants like Syngenta, Bayer, and ACI are marketing deadly poisons to the unaware farmers. This is the story of how pastors and maulanas are leading a campaign of cultural invasion taking away the very identity of the Mandi population. This is the story of how the Bangladesh Air Force goes on a daily bombing spree in Modhupur, endangering the ecological life of the area.

This is the story of how the Bangladesh state, through its forest department, is treating one of the most colourful ethnic minorities in the country as easily dispensable burdens. This is the story of how the Asian Development Bank and its evil twin the World Bank is financing projects of mass destruction in the name of development, destroying acre after acre of sal forest. This is the story of how multi-national chemical merchants like Syngenta, Bayer, and ACI are marketing deadly poisons to the unaware farmers. This is the story of how pastors and maulanas are leading a campaign of cultural invasion taking away the very identity of the Mandi population. This is the story of how the Bangladesh Air Force goes on a daily bombing spree in Modhupur, endangering the ecological life of the area. To date, officials of the forest department -- a wing under the Ministry of Environment -- religiously engaged themselves in illegal timber logging with absolute impunity. Acre after acre of sal forest -- our priceless ecological treasure -- was handed over through handsome under-the-table deals to timber merchants. Within 50 years, since the forest department took charge of Modhupur, it made sure that the forest was cut to half of its original size. And 60 species of trees, 300 species of birds? Peacock, fowl, leopard, wild pigs? Extinct. Bio-diversity, ecology? Destroyed.

To date, officials of the forest department -- a wing under the Ministry of Environment -- religiously engaged themselves in illegal timber logging with absolute impunity. Acre after acre of sal forest -- our priceless ecological treasure -- was handed over through handsome under-the-table deals to timber merchants. Within 50 years, since the forest department took charge of Modhupur, it made sure that the forest was cut to half of its original size. And 60 species of trees, 300 species of birds? Peacock, fowl, leopard, wild pigs? Extinct. Bio-diversity, ecology? Destroyed. And then, after destroying the forest, killing its bio-diversity and enforcing a regime of terror and oppression on the people, the forest department came up with an ingenious plan to erect a wall around 3,000 acres of Mandi land, in the name of "Modhupur National Park Development Project." That, anti-wall activists cried out, would destroy the lives of thousands of Mandi families in the area. "They are talking about a zoo and we all will be caged inside the wall," one adivasi activist told us.

And then, after destroying the forest, killing its bio-diversity and enforcing a regime of terror and oppression on the people, the forest department came up with an ingenious plan to erect a wall around 3,000 acres of Mandi land, in the name of "Modhupur National Park Development Project." That, anti-wall activists cried out, would destroy the lives of thousands of Mandi families in the area. "They are talking about a zoo and we all will be caged inside the wall," one adivasi activist told us. So, 8,000 acres of sal forest got wiped off the face of the earth and a rubber plantation project (that later turned out to be unprofitable, what a surprise) took shape in 1986 through 1989 with ADB finance. An ecological disaster followed as nearby paddy fields became infertile, ground water level fell, hundreds of species of birds and animals were overnight extinct. "It's poisonous, the rubber garden. You will smell poison there in the air. It's a life-threatening place where workers die every year because of poisoning," Eugene Nokrek, a Mandi activist, told us.

So, 8,000 acres of sal forest got wiped off the face of the earth and a rubber plantation project (that later turned out to be unprofitable, what a surprise) took shape in 1986 through 1989 with ADB finance. An ecological disaster followed as nearby paddy fields became infertile, ground water level fell, hundreds of species of birds and animals were overnight extinct. "It's poisonous, the rubber garden. You will smell poison there in the air. It's a life-threatening place where workers die every year because of poisoning," Eugene Nokrek, a Mandi activist, told us. These days, the banana that you have for your breakfast in Dhaka comes from Modhupur. And its nutrients: Theovit, Tilt, Karate, Ridomil, Sobricon, Gramoxcon, Rifit, Score, Ocojim, highly toxic insecticides and chemical hormones used for banana plantation.

These days, the banana that you have for your breakfast in Dhaka comes from Modhupur. And its nutrients: Theovit, Tilt, Karate, Ridomil, Sobricon, Gramoxcon, Rifit, Score, Ocojim, highly toxic insecticides and chemical hormones used for banana plantation.