Fleeing from barbarism

"Where

are you taking my husband?

"Where

are you taking my husband?

My name is Bokul Rani Das. My husband Sunil

Chandra Das was a darwan (guard) at Jagannath

Hall of Dhaka University. Before going off

for duty at 8.p.m.on the night of March

25, he told me, "You go to sleep with

the kids." I had a son and a daughter.

The girl was two and half years old. The

boy was 18 months. At around midnight the

firing started. My husband returned home

an hour later and said, "Let's escape

and hide." I was numb.

The firing was still on.

So we decided to go to the Assembly Hall.

Ten minutes after we reached there, we found

the army entering the hall and starting

to search with torches. What could we do?

Where could we hide? Their father and others

would worship Saraswati Devi. The idol was

inside the hall. Many went and hid behind

that idol. But the Punjabis hunted them

down with torches in the darkness. My girl

was in his arms. He called out to me and

said, "Hold the child." Then they

took him away dragging him by his hands.

My daughter was left on

the floor. I asked, " Where are you

talking my husband? " They said, "We

are not taking your husband anywhere. We

will bring him back". They started

to move towards the door. I tried to get

close to them, but they kicked me down.

My daughter also started to cry along with

my son. Those who were with us in the Hall

picked me up from the floor.

The Punjabis then said,

"Nothing will happen to you. Come with

us." They were talking in Hindi. I

didn't speak Hindi. Others with us there

spoke that tongue. They took me near the

gates of the assembly hall and asked me

to sit down on a stool they brought. I said,

"Bring me my husband".

They said, "No, your husband can't

be brought back. We have taken your husband

away". Others later said, they had

taken him near the big tree and shot him

there.

Our houses were torched,

we had nowhere to go. We all went to the

playing ground and sat there the whole night

as everything was in flames all around us.

When morning came, we saw that people were

being taken away to drag the corpses that

lay on the field. People were already pulling

them across the ground.

But I couldn't find my husband.

I sat on the field with my two children.

I saw that they had pulled all the dead

bodies and laid them on the ground in rows.

"You all sit down,

wear Sadarghat saris and shout 'Joy Bangla',"

-- this was what the army men said. But

nobody shouted the slogan. Then from a hole

in the wall they started to fire. When the

firing started, we all lay down on the ground.

I think I lost my senses. I have no memory

of what happened after that. But we stayed

there till the afternoon. Later those who

were still alive left the Jagannath Hall

and walked towards the Medical College leaving

the dead behind. Leaving my husband behind.

Bokul Rani Das.

Resident of Jagannath hall. Husband was

killed on the night of March 25, 1971. Interviewed

in 2002.

“It's not

safe here. Nobody knows what will happen.

What has happened? “

"We had lived in Mohammadpur all our

life. We were refugees from India and obtained

an allotment in 1962. Our area had a few

Bengali families and the line was known

as Police line because some of the residents

were linked to the police. We were very

non-political because in 1946 our family

had suffered in the Calcutta riots. I had

lost my brother then. We didn't mix much

with the Biharis.

But the Biharis were very

agitated since the non-cooperation movement

of March 1971 began. They were sometimes

worried, sometimes angry. I think most people

thought that Bhutto would not allow Mujib

to take power and nobody knew what would

happen after that. But once non-cooperation

began many became scared. Suddenly many

realised that the Biharis lived in a place

surrounded by Bengalis and they didn't like

each other.

Actually, some meetings

were held to maintain peace amongst all

but as it always happens, there were elements

that were angry and the mood became more

and more sour. We didn't know what was happening.

The local Islamic astrologers made several

dire predictions about the future. It made

us more anxious.

On 25th night I came home

early because my garage wasn't busy and

my mechanics had gone home, one to old Dhaka

and another to Syedpur. They wanted to bring

back their families. When the firing started

we all thought that a riot had broken out.

I think some people were saying "Allahu

Akbar" very loudly. We hid in the room

behind the main one. We didn't know who

was attacking whom. But we slowly understood

that it was the army. Only the army had

so many guns.

I was very scared about

being left by myself. I had a cousin who

lived in New Colony and they had a car so

I thought we could escape with them. When

morning came I asked my wife to put her

gold jewels in the bag and start moving

towards Asad Avenue. It was not very far.

My daughter was away with my wife's sister

in Moghbazar.

"Stop", I heard

a voice and stood still. It was just dawn

and the light was not yet full. We saw the

tires and tubes lying on the street and

the debris of resistance. We thought we

were going to be attacked.

Two men came towards us.

They were Biharis and I knew them. But in

that light they looked like ferocious strangers.

I was scared. They came very close to us.

I was wondering what would I do if they

tried to take my wife away. The man called

Kaleem said, " See what Joy Bangla

has done. Who will protect you now? My relatives

phoned me. They have killed many people,

many students. The army has taken charge

and now there will be no peace." He

was more morose than angry but his companion

Selim began to abuse Sheikh Mujib and blaming

him for everything. My wife started to weep.

We could hear people coming from behind.

I said nothing and taking God's name started

to move forward. When they began to shout

"Pakistan Zindabad", we ran for

our lives.

We entered Zakir Hussain

Road and hid behind a trash bin. A while

later we started to walk fast towards New

Colony.

Suddenly we saw another

family, a Bengali family walking towards

us. There faces were terrorised. "A

group of boys were stopping people and searching

them. We saw that and ran." The family

-- mother, wife, children began to run towards

some unknown direction. Suddenly we saw

our cousin hurrying on the road. He was

like a man without any blood. I have never

seen a blank face like that. He said, "It's

not safe here. Nobody knows what has happened,

what will happen." He sat down on the

road and began to cry.

Late Alfaz Hossain

Shahu

Resident of Nazrul Islam Road, Mohammedpur.

Interviewed in 2000.

"Run

away, run away”

"Run

away, run away”

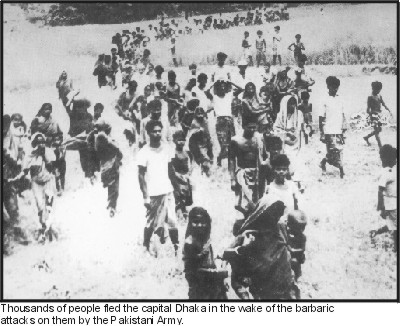

After the night of March 25 there was a

curfew. We didn't know what was going on.

We had never thought that the army would

attack us like that. We were under so much

shock that we could hardly speak. There

was no hunger only thirst and fear. Telephones

were out of order, I was very worried about

our relatives in different parts of Dhaka.

On March 27, curfew was lifted and some

people began to move. From the 26th morning

we saw the poor slum dwellers moving out

with whatever they had. But we were too

scared to make a move. Suddenly my brother-in-law

came panting and sweating. He had come from

Elephant Road. He had seen dead bodies of

the murgiwallahs at New market and had heard

of the attack on the University Halls. He

had come to warn us.

"Run away, run away",

he kept shouting. We made him sit down.

His family had already left, he said, for

his ancestral home in Keraniganj. My wife

started to cry and then the children joined.

I too was terrified as he described a city

that was fleeing from itself. I really don't

know how we did it but we decided to leave.

It can't have taken us more than fifteen

minutes before we had the handbags and some

cash with us. It was so strange that we

made sure that flag of Bangladesh was hidden

under the mattress. We didn't have the heart

to burn it.

As we took to the streets,

we didn't know where we were going but we

knew that we were leaving the city. We started

to walk holding our children's hand and

God's word on our lips. It was such a strange

sight. So many people were walking along

with us. Suddenly an army truck appeared

on the road and we began to run. We were

running from death, running from what had

become Pakistan.

A man we met as we rested

near Malibagh said everyone was going to

Sadarghat.

"The army can't cross

the river. Bengali army has taken position

there; it's safe there. " It seemed

to make sense to us all. We started to walk

towards the river. We knew we had to reach

the place before curfew was imposed again.

Jan Baksh Mollah

Bangla Motor

Interviewed in 2000

................................................................................................................

Courtesy: Interviews by

Afsan Chowdhury from his

BBC series on 1971-Liberation War.

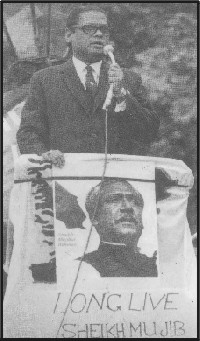

1971: Freedom struggle abroad

Mahfuz

Parvez

In March 1971, the total

number of Bengalis living in the US, including

students, visitors, itinerants, employees

in the diplomatic missions, and international

agencies, could not have been more than

4,000. But despite their meager numerical

strength, the community rose to the occasion

and made a significant contribution to the

cause of the Liberation War.

The

Bengali community living in the US in 1971

was a small one, but they all came together

to press their demands before a global audience

at the crucial time of the national freedom

movement in 1971. The Bangladesh League

of America (BLA) spearheaded the Liberation

War effort in the US. It played a prominent

role in voicing the Bangladeshi case, and

acted as a kind of guide, coordinator, and

leader among the Bengali community living

in the US in the early phase of the Liberation

War. Moreover, some Bengalis already settled

or working in the US moved to India to help

the Bangladeshi Government in Exile and

participate in the war effort directly.

The

Bengali community living in the US in 1971

was a small one, but they all came together

to press their demands before a global audience

at the crucial time of the national freedom

movement in 1971. The Bangladesh League

of America (BLA) spearheaded the Liberation

War effort in the US. It played a prominent

role in voicing the Bangladeshi case, and

acted as a kind of guide, coordinator, and

leader among the Bengali community living

in the US in the early phase of the Liberation

War. Moreover, some Bengalis already settled

or working in the US moved to India to help

the Bangladeshi Government in Exile and

participate in the war effort directly.

On March 12, the BLA held

a rally in front of the UN headquarters

in New York appealing to the world for the

right of self-determination for the Bengalis

of East Pakistan. They had the uncanny sense

of an impending disaster and appealed for

prevention of genocide in Bangladesh.

On March 23, pro-liberation

activists, primarily the Bengali employees

of the Pakistan Embassy, assembled at the

residence of Enayet Karim, Deputy Chief

of Mission, unfurled the new Bangladeshi

flag, sang the future national anthem, and

formed a committee to plan a course of action.

On March 29, a big rally

was held in Washington in which Bengalis

from all over the US participated. The rally

was a great success. At the end of the rally

nearly 70 participants gathered at the residence

of AMA Muhith, erstwhile economic counselor

to the Pakistan Embassy, to talk about the

future course of action. It was agreed that

Bangladesh associations should be set up.

Support groups of Americans and other nationals

were also to be sponsored to help the struggle

with both moral and financial backing, and

the US Congress and the administration and

national and local media were to be mobilized

to support the struggle in every possible

way.

On April 1, Senators Harris

and Kennedy made the first of the many statements

in favor of Bangladesh that the US Congress

would hear throughout the year, and on April

15, Senators Case and Mondale moved a resolution

to cut off military aid to Pakistan.

On

April 26, Mahmood Ali, Vice Consul in the

Pakistan Mission in New York, was the first

diplomat in the US to transfer allegiance.

On May 6, the Senate Foreign

Relations Committee unanimously passed the

Case-Mondale resolution on stopping military

aid or sales to Pakistan, and on May 24,

Justice Abu Sayeed Chowdhury arrived in

New York as Bangladesh's envoy to the UN.

On May 28, Ustad Ali Akber

Khan gave a recital at Berkeley to raise

funds for Bangladesh.

The month of June saw the

Bangladesh Defense League assume the role

of umbrella organization in the US, and

both Friends of East Bengal in Philadelphia

and the Bangladesh Information Center in

Washington started functioning on a formal

basis.

On June 10, Senators Church

and Saxbe moved an amendment to the Foreign

Assistance bill of 1972 to suspend aid to

Pakistan;

On June 13, a huge demonstration

was organized jointly in New York by the

BLA, Committee of Indian Associations, and

American Friends of Bangladesh (AFB).

On

June 22, there was consternation when the

New York Times published the story

of the shipment of US arms to Pakistan after

the State Department had indicated that

all military shipments had been stopped.

The information was authentic as it came

from Solaiman in the Pakistan Embassy and

was passed on to Bangladesh Information

Center by Enayet Rahim. On June 26, the

national convention of all Bangladesh Leagues

in US was held in New York and attended

by about 500 delegates.

July witnessed many dramatic

developments such as the Friends of East

Bengal picketing the Pakistani ship 'Padma'

in Baltimore on July 11.

On

August 1, George Harrison's historic Concert

for Bangla Desh was held in New York. On

August 3, the House debated the Foreign

Assistance Bill and approved the Gallagher

Amendment for denial of aid to Pakistan.

On

August 1, George Harrison's historic Concert

for Bangla Desh was held in New York. On

August 3, the House debated the Foreign

Assistance Bill and approved the Gallagher

Amendment for denial of aid to Pakistan.

The next day, all Bengali

diplomats in the US transferred allegiance

to Bangladesh, and on August 5, the Bangladesh

Mission in the US was established under

the leadership of MR Siddiqui.

AMA

Muhith and SAMS Kibria appeared on national

television to express the demand for independent

Bangladesh. On 26 August 26, Senator Kennedy

held a press conference in Washington describing

his visit to Bengali refugee camps and accused

the US administration of complicity in genocide.

In September, the Bangladeshis

organized demonstrations in front of the

conference hall where the World Bank was

meeting, and on September 30, the third

sub-committee hearing on the refugee crisis

was held with eminent people giving testimony.

In October several demonstrations

and campaigns took place. On October 1,

the Bangladeshi Delegation to the UN General

Assembly held a press conference in New

York, and on the 16th began a 5 day publicity

campaign in Washington in favor of Bangladesh.

A ten-day demonstration was held in Lafayette

Park in front of the White House from October

14.

On October 21, world-famous

musician Ustad Ravi Shankar gave a concert

in Iowa City for Bangladesh freedom movement,

and a week later, Joan Baez gave a concert

in Ann Arbour, Michigan to promote the Bangladesh

struggle.

On November 3, a nation-wide

Fast to Save the People was organized in

many educational institutions. The next

day, Indian leader Indira Gandhi landed

in Washington, and met with President Nixon,

Congressional leaders and Bangladesh Mission

staff.

On November 5, Senator Harris

proposed an emergency meeting of the Security

Council to resolve the Bangladesh crisis.

On November 8, arms shipments to Pakistan

were finally stopped, and two days later,

the Senate finally passed the Saxbe-Church

amendment;

On November 26, NBC broadcast

a two-hour program on Bangladesh which only

marshaled more support for the cause. PBS

organized a nationally televised program

on Bangladesh called Advocate. The Pakistani

case was supported by Congressman Peter

Frelinghuysen of New Jersey, Ambassador

Benjamin Ohlert of Pepsi-Cola (who was once

ambassador to Pakistan) and a video interview

of ZA Bhutto. Rehman Sobhan and John Stonehouse,

a British MP advocated the Bangladeshi case,

and Acting Ambassador MK Rasgotra explained

the Indian position.

On December 3, the criticism

of India by the US Administration turned

bitter as the Liberation War turned into

a sub-continental war. The next day, Senator

Harris resubmitted his resolution for a

special Security Council initiative for

resolving the crisis and seven important

senators from both parties supported him.

Time

once again came out with a cover story captioned

"Conflict in Asia: India versus Pakistan"

and simultaneously Newsweek made

its cover story "India Attacks: The

Battle for Bengal."

On December 9, Congressman

McCloskey asked for the recognition of Bangladesh

and Congressman Helstosky moved a resolution

for granting recognition to Bangladesh.

As

it became obvious that Bangladesh would

be liberated soon, Kissinger continued to

try his best to get the Chinese involved

in the war. Nixon and Kissinger delayed

the surrender of Pakistani forces by five

days and even went to the extent of threatening

to move the nuclear vessel Enterprise towards

the Bay of Bengal. While the US administration

made every effort to save Pakistan, the

US Congress and the media displayed neutrality

by supporting the birth of Bangladesh.

As

it became obvious that Bangladesh would

be liberated soon, Kissinger continued to

try his best to get the Chinese involved

in the war. Nixon and Kissinger delayed

the surrender of Pakistani forces by five

days and even went to the extent of threatening

to move the nuclear vessel Enterprise towards

the Bay of Bengal. While the US administration

made every effort to save Pakistan, the

US Congress and the media displayed neutrality

by supporting the birth of Bangladesh.

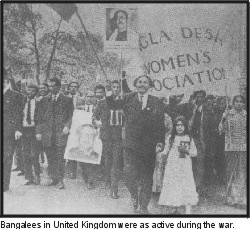

During 1971, the small Bangladeshi

community living in the US performed a significant

role in moulding public opinion in favor

of the Liberation War. Their activities

were focused primarily on organizing the

community into groups with the goal of working

collectively to raise funds to contribute

to refugee relief efforts and to supply

equipment to the Bangladesh Government in

Exile; collecting and disseminating information

to Americans; engaging in lobbying campaigns

with policy-makers like the members of Congress,

other American establishments, and international

agencies; providing support for the creation

of a national coordinating committee for

developing a concerted plan; and organizing

and participating in demonstrations and

rallies. Many well wishing Americans also

actively participated in all of the above

activities.

The

staunch and timely support for the cause

of Bangladesh, therefore, came from a wide

spectrum of people, from academicians and

dock-workers, from members of Congress and

activists, from media and musicians, from

poets and performers. Their advocacy certainly

went a long way to creating a favorable

popular demand, strong enough to force the

US administration to ease their anti-Bangladesh

stance over time. The Bengali community

living in the US in 1971 and some humanist

Americans can certainly claim a share of

the credit for the ultimate success of the

Liberation War.

...............................................................................................

The author is Associate Professor in the

Department of Political Science, University

of Chittagong.