Story of a patriot

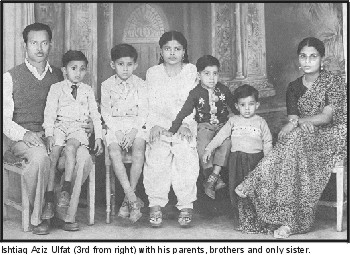

Ishtiaq

Aziz Ulfat

He

was the first born, the coveted one, he

was the sunshine of my parents, the special

one in the family. And special he was. He

was over six feet tall, lanky yet handsome.

He was naturally charming and full of life.

He always left behind a little of himself

in which ever path he walked, whomever he

came across. I guess, that is why even thirty

three years after his death his friends

and everyone who used to know him speak

of him so fondly, taking pride in their

acquaintance with him. It is as if they

still derive some nobleness, some modesty

by knowing, by being associated with this

gallant, noble yet gentle human being.

He

was the first born, the coveted one, he

was the sunshine of my parents, the special

one in the family. And special he was. He

was over six feet tall, lanky yet handsome.

He was naturally charming and full of life.

He always left behind a little of himself

in which ever path he walked, whomever he

came across. I guess, that is why even thirty

three years after his death his friends

and everyone who used to know him speak

of him so fondly, taking pride in their

acquaintance with him. It is as if they

still derive some nobleness, some modesty

by knowing, by being associated with this

gallant, noble yet gentle human being.

This

was Abu Moyeen Mohammad Ashfaqus Samad.

A long name indeed which is why his friends

had affectionately cut it down to Ashfi.

Though his nick name was Nishrat, my parents

had a special name for their special son;

they lovingly called him Tani. We younger

siblings according to custom called him

Bhaiya. But by whatever name he was called

it didn't matter. All loved him. It is indeed

very difficult to accept his death, especially

an untimely death. He was just 21, gone

from us forever.

Lt

Ashfaqus Samad has been laid to rest close

to where he had breathed his last, in Joymonirhat

in Rangpur district, having been killed

in a frontal battle against the occupation

Pakistani Army in the Liberation War of

'71. The only solace is that he laid down

his life to liberate his motherland, that

he died in free territory and that he breathed

free air before he died. He was brave and

he died young.

The

Pakistani Army's brutal assault on the unarmed

people of Bangladesh (the then East Pakistan)

coincided with the end of his honours final

of DU. His subject was statistics and he

was awaiting a reply from MIT in Chicago

where he was seeking admission. But who

knew then that he had been chosen for a

bigger and better task, to serve his nation,

to die for it and thus live forever. Who

could ask for more?

The

night of 25th March in 1971

On the fateful night of the 25th of March

we were standing around the traffic circle

in front of The Daily Ittefaq office. The

street was full of people, and everybody

in a state of tense apprehension, full of

energy, but did not know what to do. We

first saw two flares shooting up at the

sky around 10 pm. The first one going up

around the Gulistan area and the other one

above the Rajarbagh police line. Even after

all these years I can clearly picture the

"fireworks", as if some thing

that was happening just last night. The

light from the flares lighting up the dark

sky some how signaling the end of an era

and the beginning of another -- the end

of Pakistan (as it was) and the beginning

of Bangladesh. I say this today in retrospect

because at that moment we really could not

anticipate the magnitude of destruction

and horror that the Pakistan Army had let

loose on the innocent people of Bangladesh

on that fateful night.

We

heard the sounds of gunfire a few minutes

after seeing the flares, but the tanks actually

rolled in around midnight. They took their

position by the same traffic circle where

we were standing a little while ago and

fired the first shells targeting the Ittefaq

office. The shellings shook our house. Very

soon the newspaper office was ablaze and

the flame went sky high. Our house being

only a 100 yards away started getting the

heat. The iron bars on the windows started

to get hot and we kept pouring water on

them fearing that the wooden window shutters

might catch fire at any moment. Most of

the employees of the press had crossed over

to our house and went to safety through

the back, except the ill-fated ones who

took the direct hits. The fires and shootings

raged on for about two hours after which

things started quieting down, except occasional

gunshot sounds. Even then we were so scared

that we all huddled together all night long

on the ground floor in a narrow space under

the staircase. The next morning we crossed

over the wall to see the damage next door.

It was the first of the many horrendous

sights that I would witness over the next

few months till liberation. There were about

a dozen bodies, scattered all over the machine

room of the press, most of them burnt beyond

recognition.

We

were all confined to our house, glued to

the radio till the next morning, when curfew

was lifted for a couple of hours. In spite

of my mother shouting at us not to leave

the house we strayed out. Having gone just

about 500 yards from our house I came across

a scene which really changed my whole attitude

towards life -- a small boy aged about ten

had tried to crawl under a gate, probably

when he had found the gate too high to cross

over. The marauding Pakistani army had shot

him dead as he had just put his head through

the gap under the gate and there he was

lying in a dried up pool of blood. This

was when I realised that it was all over,

that we were no longer Pakistan and that

we were a new nation and we must now fight

for our liberation and fight for a free

Bangladesh. My friends and I continued to

move about and went to Shakari Bazar into

old town, where we saw that most of the

houses were burnt, looted and marked with

bullets. In one of the houses we saw another

heart rendering scene; two bodies clinging

together burnt to the bone as if making

a statement saying, "together -- even

in death". From here we went on to

Jagannath Hall at Dhaka University where

a huge number of students had been killed

and the bodies were littered all over. On

the field next to it we saw the hastily

made mass graves of the ill-fated who were

lined up, shot and killed; their hair, clothes

and limbs still showing through the grass.

(This killing was later shown on TV after

liberation as it had been taped by some

amateur photographer)

We

were all confined to our house, glued to

the radio till the next morning, when curfew

was lifted for a couple of hours. In spite

of my mother shouting at us not to leave

the house we strayed out. Having gone just

about 500 yards from our house I came across

a scene which really changed my whole attitude

towards life -- a small boy aged about ten

had tried to crawl under a gate, probably

when he had found the gate too high to cross

over. The marauding Pakistani army had shot

him dead as he had just put his head through

the gap under the gate and there he was

lying in a dried up pool of blood. This

was when I realised that it was all over,

that we were no longer Pakistan and that

we were a new nation and we must now fight

for our liberation and fight for a free

Bangladesh. My friends and I continued to

move about and went to Shakari Bazar into

old town, where we saw that most of the

houses were burnt, looted and marked with

bullets. In one of the houses we saw another

heart rendering scene; two bodies clinging

together burnt to the bone as if making

a statement saying, "together -- even

in death". From here we went on to

Jagannath Hall at Dhaka University where

a huge number of students had been killed

and the bodies were littered all over. On

the field next to it we saw the hastily

made mass graves of the ill-fated who were

lined up, shot and killed; their hair, clothes

and limbs still showing through the grass.

(This killing was later shown on TV after

liberation as it had been taped by some

amateur photographer)

Bhaiya

left home for the first time on 27 March,

1971. At that moment it was only he who

knew that he was going to return shortly.

On April 4, Bhaiya and three of his close

friends made their way back into Dhaka.

They had brought back with them six 303

rifles, 25 grenades and several hundred

rounds of ammunition. They had done this

at a time when most others were either making

their way out of Dhaka to safety or were

thinking about it. He had done this act

when it was unthinkable. Yes, Bhaiya and

his friends were the first guerillas to

have taken up arms against the Pakistani

Army in Dhaka City. Bhaiya's other friends

were Shahidullah Khan Badal, Masud Omar

known more to his friends as Masud Pong,

and Badiul Alam Bodi who was later picked

up by the barbarian Pak army and was tortured

to death.

Bhaiya

and his friends had acquired these arms

from Kishoreganj where Major Shafiullah

had positioned himself with 2nd Bengal.

Badal Bhai had established contact with

Lt. Helal Murshed, and their trust further

cemented when Col Zaman (later on Commander

of Sector 6) had found his way there. Major

Khaled Musharraf with his 4th Bengal were

heading north towards Akhaura from B'baria,

and Lt Mahbub also arrived in Kishoreganj

to establish contact with the other fragmented

resistance forces. Later on Shafiullah,

Khaled and Zia and others were to congregate

at Teliapara is Sylhet at a tea estate where

the first training camp for the FFs was

to be established.

Bhaiya's

group of four having arrived in Dhaka around

dusk chose to halt for the night at our

house. We had no clue of what they were

up to, but they had to take my father into

confidence, and my father, a man born with

raw courage always stood by his children

and encouraged them in all their naughty

but bold and creative acts. They smuggled

the arms to our roof only to be shifted

to another friend's house in Dhanmondi the

next day, this friend being Tawhid Samad

and another recruit of that moment was their

friend Wasek. But it didn't take them very

long to realise that they could do little

with their new found arsenal. Bhaiya and

his friends decided to go up north and join

with the resistance forces there. Only Bodi

Bhai stayed back.

In

the meantime my second brother Tawfiq had

also left home to join the resistance struggle

at Roumari in Rangpur where he had some

friends. I also left home with a couple

of friends on the 18th of April, and after

about two weeks on the road we managed to

reach Agartala, from where we eventually

ended up at Matinagar, Sonamura, the first

training camp for Freedom Fighters at that

Sector, which was later on moved to Melaghar.

Here we took crash courses on small arms

and explosives from Capt Haider. We were

amongst the first batches of trained guerillas

who initiated sabotage operations in Comilla

and Dhaka. Later on in Dhaka we joined up

with the same group which Badal Bhai and

Bhaiya had organised before their departure

from here. We worked with this cell and

organised and recruited many more Freedom

Fighters who undertook many small and big

operations in the city.

Bhaiya

had come home to Dhaka for the last time

in early June and that was the last time

that his near and dear ones saw him. Soon

after his return to camp he was selected

for training as a commissioned officer where

he successfully completed his training and

was sent to liberate areas in the northern

part of Bangladesh. He was now Lt Asfaqus

Samad with his own company to lead. He and

his company liberated many areas of Bangladesh

till they reached a place called Raiganj,

forty kilometres north-west of Kurigram.

The Pakistan Army had set up a strategic

stronghold there. If they could be routed

from this bastion the occupation army's

next line of defence would recede to Kurigram.

Lt Samad and his fellow officers were planning

to launch an attack on this stronghold when

he received orders transferring him to Sector

Headquarters. His reaction was typical of

him. He sent a message through courier that

he would report to duty in a few days time.

He did not want to miss the big assault.

After all he and his colleague Lt Abdullah

had been planning it.

The

date of the assault was fixed for Nov 19,

1971. Ironical as it may seem, it was the

same day that his parents, being haunted

by Pakistan army due to their son's involvement

in the freedom struggle had left Dhaka for

sanctuary, either in a liberated area or

in India, where they had also hoped to meet

their beloved son. While Lt Samad's parents

embarked on this perilous trip towards the

west, Samad himself was sitting in a bunker

way up north preparing his line of attack

on the Pakistanis.

The

occupation Army's position was strong indeed.

Over the bridge on the river Dudhkumar they

had placed six medium machine guns. Across

the river they held fortified positions

in several buildings where there were at

least three more heavy machine guns with

them. The enemy had a good sight over the

plain area on the west of the river.

The

Mukti Bahini and the allied forces decided

to launch a five company strong attack --

two of the companies were of the Mukti Bahini

commanded by Lt Samad, one was a Rajput

company commanded by Major Opel of the allied

army and two companies were of the Border

Security Force. They would advance in the

dark of the night, dig in their positions

on the bank of the river and take on the

enemy.

The

advance was smooth. Digging in was about

to begin. Then there was an explosion. A

mine had exploded somewhere near the position

of the Rajput company. The occupation hordes

opened up with every thing they had.

Lt

Samad's reaction, who was in one flank,

was instantaneous. He ordered his troops

to retreat a few hundred yards and take

cover. He then ordered his faithful JCO

to leave his wireless set behind and go

back to join his troops. He himself would

call in artillery support. He would not

budge from his own position. Realising the

danger his JCO did not want to leave his

Commander.

Meanwhile

the situation had become precarious. The

Mukti Bahini companies as well as those

of the allied forces were finding it difficult

even to take cover. Firing from the enemy

was intense. Lt Samad took his second and

last decision. He shifted his position a

little and moved his own medium machine

gun with him. Then he opened up with his

weapon to give cover to his troops. The

enemy immediately concentrated all its fire

on the young soldier. The unequal fight

lasted for twenty minutes, but valuable

twenty minutes in which time the Mukti Bahini

troops had reached safety. Suddenly after

those breath taking twenty minutes the soldiers

on the liberation army could not see any

more spitting of fire from Lt Samad's machine

gun.

The

faithful JCO made a daring trip back to

his commander's position. There he found

the commander lying motionless. A bullet

had pierced through his forehead. But there

was no sign of agony on his face. He was

lying in peace. Only his fingers were clenched,

those long thin fingers which people say

is a mark of artistic inclination, those

fingers which Lt Samad's father and mother

so lovingly caressed and kissed even after

he had grown up. Gone was the darling of

Mr. Azizus Samad, a lion of a father, best

friend to his children, who had suffered

indescribable misery and torture in the

hands of the Pakistan army who had come

looking for his guerilla sons. Gone was

the darling of Mrs. Sadeqa Samad a prize-winning

teacher, a Fulbright Scholar, an Honorary

Judge whose mission in life was to love

other's children and educate them. Gone

was a valiant freedom fighter. And as long

as they lived never had a day gone by with

out his mother shedding tears for her son,

never had a moment gone by without his father

gazing out of the window, may be thinking

about his son, or may be wandering about

him and wishing for death to embrace him

at its earliest, so that he could join his

beloved son his beloved Tani.

The

soldiers who fought under Lt Samad's command

loved him true and they fought a fierce

battle to recover his body, in the process

five of them laid down their lives. They

also held their mission dear. They and the

allied forces finally overran the occupation

army position. In the battle Major Opel

also laid down his life. The allies confirmed

their friendship in a stream of blood. After

the victory the soldiers performed the last

rites of their fallen commander and comrades.

Lt Samad and three of his comrades were

laid to eternal rest in a Joymonirhat mosque

compound with a 27 gun salute.

The

soldiers who fought under Lt Samad's command

loved him true and they fought a fierce

battle to recover his body, in the process

five of them laid down their lives. They

also held their mission dear. They and the

allied forces finally overran the occupation

army position. In the battle Major Opel

also laid down his life. The allies confirmed

their friendship in a stream of blood. After

the victory the soldiers performed the last

rites of their fallen commander and comrades.

Lt Samad and three of his comrades were

laid to eternal rest in a Joymonirhat mosque

compound with a 27 gun salute.

May

be Lt Samad had an ordinary death in an

ordinary Battle but ordinary he was not.

Uncanny as it may sound, two statements

on two different occasions still make me

wonder about something extra ordinary about

him. Once in a conversation with my mother

he had said in a matter of fact way, "Amma,

we are four brothers, can't you dedicate

just one for a greater cause, for the Liberation

of our Motherland?" Naturally he had

not expected an answer from her. But little

did we realize that he was speaking of himself

in a surrealistic way, or did he?

Another

time replying to a letter received from

his friend Ruma, he wrote on the 3rd of

Nov 1971, "It is nice to receive your

lovely letter here at the battle front.

Your letter reminds me in this bunker, amidst

all these explosions that there is another

world out there beyond this arena of death

& destruction." He did not forget

to make a point of the main purpose of his

being out there at the front, fighting a

war. And so without even realizing he patriotically

wrote, "You should be glad to know

that I am writing to you from a free territory

of Bangladesh and I have to tell you that

I never realized how sweet it is to smell

and breathe free air in free Bangladesh."

But at the end he did not forget the reality

around him, and that death might be just

round the corner which is so common fold

in war. In the last paragraph he writes,

"I liked your poem immensely. So, it

seems that there will be a poem or an epitaph

inscribed on our mass graves. I propose

that you write it. And of course do not

forget to leave a flower."

Souls

like Ashfaqus Samad and thousands like him

have sacrificed their lives so that we have

a free land of our own, a land to develop

or to destroy. Our land liberated by us,

to be ruled by us, our destiny in our own

hands.

Let

us believe this "worst of times"

we are in, shall pass too and a new generation

will be born. And they will see to it that

all crisis is over come, that all challenges

are met with bravery, just as our generation

did in 1971. Yes, patriots will again be

born -- if need be they will rise from the

Ashes.

.........................................................

The writer was a Freedom Fighter in Sector-2.

Date

-March 25, 1971

Target - Dhaka University

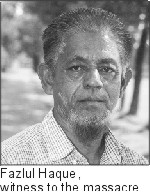

Fazlul

Haque, a guard at Iqbal Hall (now Jahurul

Haque Hall) describes the brutality of the

Pakistani Army on the night of March 25,

1971:

At

8:00 PM, Jatiya Samajtantrik Dal (JSD) leader

Sirajul Alam Khan came to the hall and requested

us to leave the hall quickly as the Pakistani

army might attack. He also directed us to

make barricades on the roads. The students

and staff began leaving the hall. At 10:00,

I left the hall and went home after completing

my duties. My home was just on the bank

of the western part of the hall's pond.

At

8:00 PM, Jatiya Samajtantrik Dal (JSD) leader

Sirajul Alam Khan came to the hall and requested

us to leave the hall quickly as the Pakistani

army might attack. He also directed us to

make barricades on the roads. The students

and staff began leaving the hall. At 10:00,

I left the hall and went home after completing

my duties. My home was just on the bank

of the western part of the hall's pond.

At midnight, the Pakistani

Army began their attack on the hall. Tanks

and jeeps entered the hall from the south-east

gate and later more army came through the

main gate. The hall came under a barrage

of heavy mortar and machine-gun attack from

near the pond in front and the police barracks

behind it. Immediately, students and bearers

from the hall and the Bengali policemen

from the Nilkhet barracks tried to escape

and seek refuge in the adjoining teachers

and staff quarters.

The army set the Nilkhet

slum on fire and in cold-blood machine-gunned

the fleeing slum dwellers. Many managed

to escape from the slum and also took shelter

in the staff quarters. The army also set

fire to the Palashi slum. The machine gun

attack on the hall set student rooms ablaze.

The hall, two slums, and a staff quarter

building were burning. The army shot a flare

lighting up the sky, and I saw about 1000

soldiers had taken position.

The sound of shells bursting

and guns firing, the smoke and fire, the

smell of gun-powder, and the stench of the

burning corpses, all transformed the area

into a fiery hell. The incessant firing

from mortars, tanks, and machine-guns continued

through the night. Huge gaping holes appeared

in the hall and the adjoining residences

of the bearers as a result of the shelling.

On the morning of the 26th, the Pakistani

killers began to go through the hall rooms

and began their orgy of murder and looting.

The army searched all through

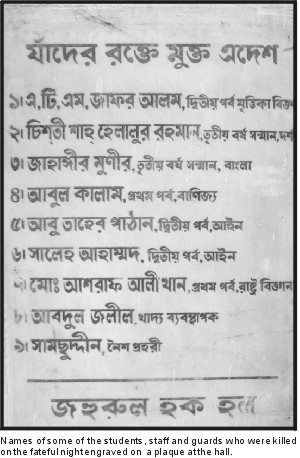

the hall and killed at least seven students.

The unfortunate students were ATM Zafor

Alam, Jahangir Munir, Abul Kalam, Abu Taher

Pathan, Saleh Ahmed, and Mohammad Ashraf

Ali Khan. Shamshuddin, a night guard of

the hall who was locked at the hall provost

office, was burnt alive when the army threw

petrol bombs inside the office.

Chisty

Sah Helalur Rahman, the Dhaka University

correspondent for the Daily Azad was shot

in the early morning at the wall of the

house tutors quarter, near the water pump.

Abdul Jalil, food manager of the hall, was

killed beside my house at the western part

of the hall's pond. The water pump workers

of the hall were also killed.

Chisty

Sah Helalur Rahman, the Dhaka University

correspondent for the Daily Azad was shot

in the early morning at the wall of the

house tutors quarter, near the water pump.

Abdul Jalil, food manager of the hall, was

killed beside my house at the western part

of the hall's pond. The water pump workers

of the hall were also killed.

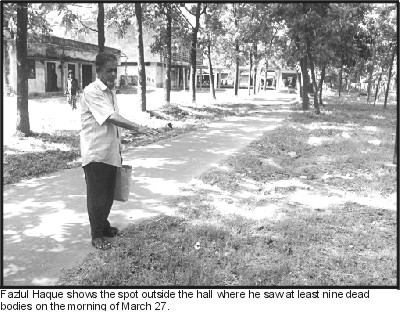

Having

finished their slaughter at Iqbal Hall,

the Pakistani army turned their attention

to the residential buildings. They murdered

DU teacher Professor Fazlur Rahman and two

of his relatives on March 26. We came to

the hall on March 27 after withdrawal of

curfew. I saw nine dead bodies beside the

road at the hall playground and seven bodies

on the ground near the quarter of the house

tutors. I have never seen brutality like

that of the Pakistani army on March 25,

1971.

Abdus

Sobhan, TV room caretaker of Iqbal Hall

(now Jahurul Haque Hall) describes the carnage:

We were informed at about

8:00 that the Pakistani army might storm

the hall. Hearing the news, almost all the

staff and students left the hall, though

many returned after a few hours. I could

not go because I was on duty in the TV room.

When my duty ended at 10:00,

I left the hall for safety with two colleges,

Shamsu and Sattar. In the middle of the

hall playground, we stopped and saw a number

of jeeps and tanks carrying the Pakistani

army were coming towards the hall through

the road behind the Muslim Hall (Salimullah

Hall) near the British Council.

Being

intrigued, I stopped for a few seconds in

the middle of the playground to observe.

I came to the south-west part of the playground

where there was a tamarind tree. Karim,

a Bihari used to sleep under the tree. I

took shelter in between two houses of hall

staffs and caught sight of the Pakistani

army coming towards the tree. The army roused

Karim and talked to him.

Taking Karim with them,

the army then moved to the south-eastern

part of the pond and took shelter there.

I heard a gunshot from the staff quarter.

At midnight the hall came under a barrage

of heavy mortar and machine-gun fire. The

Army set the Palashi slum on fire. The heaped

bodies of the dead from the slum were also

set on fire near the Nilkhet rail gate petrol

pump.

Some

surviving students were taken to the Iqbal

Hall kitchen where petrol was poured over

them and they were burnt alive. The university

correspondent of the Daily Azad was shot

near the water pump in the early morning.

So was bearer Shamshu. The water pump workers

of the hall as well as the bearers were

all brutally murdered by the Pakistanis.

Some

surviving students were taken to the Iqbal

Hall kitchen where petrol was poured over

them and they were burnt alive. The university

correspondent of the Daily Azad was shot

near the water pump in the early morning.

So was bearer Shamshu. The water pump workers

of the hall as well as the bearers were

all brutally murdered by the Pakistanis.

I

took shelter besides the houses of the staff.

The Pakistani army continued firing till

morning. They entered the hall at dawn.

We then moved to the Home Economics College

and took shelter on the second floor of

a decayed building. I could hear the cracking

sounds of bullets, the students and staffs'

pleas for mercy, and the sound of the soldiers

ransacking every room in the hall.

We could also hear the army

dragging two or three persons, perhaps students,

out from the hall. The army also dragged

out another two or three persons behind

the hall's canteen. After some time, we

observed the army was out of sight, and

began to return ,but approaching the hall

we saw the army still there. We ran back

to the Home Economics College. I was injured

seriously in my head. Some of the people

thought I had been shot. They took me away

and gave me primary medical treatment.

After few hours we returned

to the hall. Sattar, one of the hall staffs,

in an emotion-choked voice, requested me

to go with him to the provost office. He

said that his father might be there. I went

with Sattar and we found his father dead

inside the office. We also found several

dead bodies at the playground and two bodies

at the roof of the Mosque and one student's

body in his room.

...........................................................................................

As told to Hasan Jahid Tusher.