|

||||||||||||

Working democracy: A stocktaking--Dr. Kamal Hossain Politics invading culture--Serajul Islam Chowdhury Bangladesh at 40: Addressing governance challenges -- Barrister Manzoor Hasan, Dr. Gopakumar Thampi and Ms. Munyema Hasan Party government and partisan government-- Dr. Mizanur Rahman Shelley Is rule by the majority enough?-- Mohammad Abu Hena The rubric of good governance --Mohammad Badrul Ahsan For a human rights culture -- Professor Dr. Mizanur Rahman For an independent Human Rights Commission-Sayeed Ahmad Of this and that -- Sultana Kamal Tribalist corruption-- Mohammad Badrul Ahsan Fighting terrorism: Enforcement challenges--Muhammad Nurul Huda Combating corruption: People are watching-- Iftekharuzzaman E-government and its security-- Dr. M Lutfar Rahman CHT Accord: Implementation a half empty glass -- Devasish Roy Wangza Citizenship and contested identity: A case study -- Bina D'costa and Sara Hossain Forty years of "yes ministership"-- Mahbub Hussain Khan Politician-bureaucrat interface-- AMM Shawkat Ali Impartial bureaucracy: A fading dream-- Nurul Islam Anu Forty years... and diverse governments--Syed Badrul Ahsan Protect environment, save the nation--Morshed Ali Khan

|

||||||||||||

Photo : Star Archive |

||||||||||||

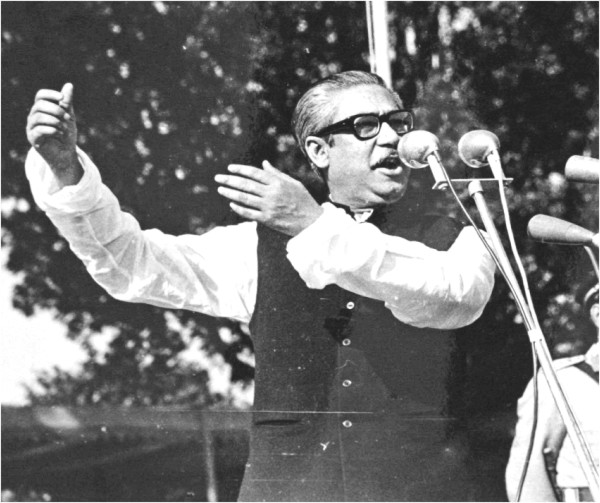

Forty years . . . and diverse governments Syed Badrul Ahsan Bangladesh has gone through a rather bizarre trajectory in governance, indeed in the way its governments have shaped up, have fizzled out and then have come up in newer raiment. It was not supposed to be this way, given the truth that the Bengali struggle for autonomy in pre-1971 Pakistan was fundamentally aimed at a restoration of parliamentary government in the country. Be it noted that the parliamentary system of government in Pakistan was put paid to through the declaration of martial law by President Iskandar Mirza and Army Chief General Ayub Khan in October 1958. That did not, of course, prevent the political parties, particularly the Awami League, from waging a relentless struggle for a return to a political system where parliament would once more be the focal point of governance. Their efforts bore fruit when, days before finally calling it quits, President Ayub Khan told a round table conference of ruling and opposition political leaders he had convened in Rawalpindi in March 1969 that parliamentary government would be restored and general elections on the basis of one-man one-vote would be organized. Ayub's successor, General Yahya Khan, upheld the decision, organizing national and provincial assembly elections all across the country between December 1970 and January 1971. We will not go into a retelling of the story which subsequently shaped up. Suffice to say for now that Bengali aspirations, as articulated by Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and the Awami League within the context of the Pakistan federal structure, were to be rudely shattered by the refusal of the military-civilian bureaucratic complex based in Rawalpindi to hand over power to the elected representatives of the people. The mistake was compounded by a blunder: the launch of a genocide on March 25, 1971 in East Pakistan which was to precipitate Bengalis' determination to end their association with Pakistan through a concerted guerrilla warfare against what was now an army of occupation from Pakistan. It was a radical Bangladesh, in the sense that its people, always having believed in constitutional politics and traditionally upheld culture as a defining fact of life, had accomplished a revolution through a war of liberation. And yet, despite the sea change brought about by this revolution, the People's Republic of Bangladesh was not to be pushed off its original goal of seeing the country governed under a parliamentary pattern of government.

Early stages

Bangabandhu as Prime Minister Bangabandhu's government was predictably buffeted by challenges on various fronts right from its inception. The damage to the nation's infrastructure had been immense during the War of Liberation; three million Bengalis had been killed by the occupation Pakistan army and 200,000 Bengali women had been raped by Pakistan's soldiers. Internationally, even though Bangladesh was swiftly coming by recognition as an independent state from other nations, it found its way into the United Nations blocked by China's veto, which act was meant by Beijing as a sign of solidarity with Pakistan. Even so, the government achieved some remarkable feats, significant among which was the withdrawal of the Indian army from Bangladesh by mid March 1972. In December of the year, the Constituent Assembly ratified the Constitution on the basis of which the country's first general elections were held on March 7, 1973. The Awami League was returned to power with a huge majority.

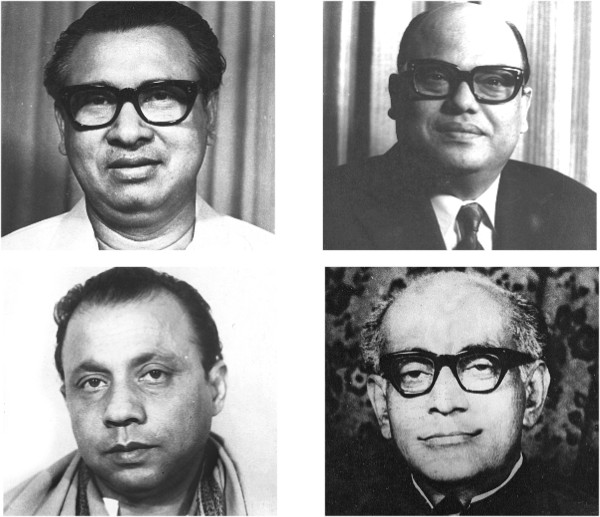

Fourth Amendment August 1975 coup The Moshtaque regime abolished the BAKSAL system and clearly meant to steer the country towards the political right. As a way of providing immunity from future prosecution to Bangabandhu's assassins, now running the show, the regime promulgated the notorious Indemnity Ordinance. On its watch and on its clear directives, Syed Nazrul Islam, Tajuddin Ahmed, M.Mansoor Ali and AHM Quamruzzaman, then detained in Dhaka central jail, were brutally murdered on the night between November 3 and 4, 1975. Counter coup Khaled Musharraf's ascendancy led to his appointment by Moshtaque as the new chief of staff of the army. General Ziaur Rahman was placed under internment at his residence in the cantonment. Musharraf was promoted to the rank of major general. The new army chief had Khondokar Moshtaque removed from the presidency on November 6 by the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, Abu Sadat Mohammad Sayem. General Musharraf's coup fell through at dawn on November 7, when forces loyal to Zia and led by Col. Abu Taher, a war hero, stormed Musharraf's soldiers and freed Zia from confinement. Khaled Musharraf, Huda and Haider were murdered by Zia loyalists in the army in the morning. By the end of the day, President Sadat, kept on by the new men in charge, had assumed the position of Chief Martial Law Administrator in addition to keeping his place as head of state. Zia, along with the chiefs of the air force and navy, was appointed deputy martial law administrator. On Sayem's and Zia's watch, Col. Abu Taher, the man who had freed Zia from house arrest on November 7, 1975, was tried in court martial on charges of instigating indiscipline in the army and hanged on July 21, 1976. In December 1975, the regime repealed the Collaborators Act of 1972, thus making the way clear for a return to politics of elements who had directly collaborated with the Pakistan occupation army in 1971.

The Zia years Worse, the Indemnity Ordinance promulgated by Moshtaque now became part of the Fifth Amendment. The killers of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman were now under constitutional protection! General Ziaur Rahman was assassinated by soldiers of the Bangladesh army in an abortive coup on May 30, 1981. Vice President Justice Abdus Sattar swiftly took over as Acting President of Bangladesh. In a new presidential election held on November 15, 1981, Justice Sattar was elected President in his own right, defeating Dr. Kamal Hossain of the Awami League. Ershad's long reign As political opposition to Ershad's military rule mounted, he engaged in a process of drawing leading politicians away from the major political parties, the Awami League and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party, eventually forming the Jatiyo Party. Ershad organized parliamentary elections in 1986 in which the Awami League took part. The BNP boycotted it for, in its view, the entire process was an illegitimate one. By 1988, the Jatiya Sangsad would be dismissed and fresh elections called. These new elections were boycotted by both the Awami League and BNP, which were then engaged in serious agitation against the regime. The AL-led fifteen party alliance and the BNP-dominated seven-party alliance called an endless series of hartals and other forms of civic protest which by the end of the 1980s effectively left the Ershad regime paralysed. President Ershad and his government capitulated on December 6, 1990. Shahabuddin Ahmed, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, took over as Acting President under a caretaker formula earlier agreed upon by the two major political alliances and accepted by a tottering military regime. Justice Shahabuddin set about arranging fresh general elections to parliament, which would be held in February 1991. The general elections of October 2001 saw the BNP return to office. Its new stint in power was marked by a rise in corruption, symbolized by the presence of alternative centres of power manned by individuals close to Prime Minister Khaleda Zia. The BNP left office in October 2006 through handing over power to a new caretaker administration led by President Iajuddin Ahmed. Dogged by controversy from the beginning, the Iajuddin government soon gave way to a second caretaker government led by Fakhruddin Ahmed and backed by the military. In an unprecedented stint in office for a caretaker government, of nearly two years, the caretaker government busily set about reforming such institutions as the Anti-Corruption Commission, the Public Service Commission and the Election Commission. Politicians, including Sheikh Hasina and Khaleda Zia, were placed under arrest. Leading political figures, academics and businessmen were placed on remand on various charges and subjected to brutal treatment at the hands of security forces. Eventually, though, all detained individuals were freed and general elections were held in late December 2008. The Awami League returned to office with a three-fourths majority. The state of the nation, for all the hope engendered by the many movements for democracy and the triumph of the popular will over the decades, remains tenuous. There is yet a long way to go before democracy can take deeper roots in Bangladesh. Syed Badrul Ahsan is Editor, Current Affairs, The Daily Star

|

||||||||||||