| Cover Story

From Insight Desk

Qamrul Hasan and the Folk Tradition

Often reproached by the avant garde group of abstract painters for his anchored world of traditional vision, Qamrul Hasan emphasizes the folk element in art where figures are stylized, pigments are loud and brash, and primitive instincts are the motive force of life. The wellsprings of his inspiration are his own people engaged, as he puts it, “in the fascinating task of day-to-day living”. Often reproached by the avant garde group of abstract painters for his anchored world of traditional vision, Qamrul Hasan emphasizes the folk element in art where figures are stylized, pigments are loud and brash, and primitive instincts are the motive force of life. The wellsprings of his inspiration are his own people engaged, as he puts it, “in the fascinating task of day-to-day living”.

S N Hashim

It was 20 years ago, late in 1946, that I first saw the paintings of Qamrul Hasan. It was a motley collection, as I recall, of his early works. Being young and impressionable myself I remember breaking into ecstatic praise.

Now, with the distance of two decades and almost a lifetime of his artistic career and reputation, I can still remember patches of finished glory, such as the approaching rains over a wide expanse of rice-fields, the watercolour washes sensitive to the dampness of the impending deluge, tinged with the sadness of separation and longing. No other painter that I know of has been able to capture the subtle half-tones of shifting light and shade of this particular scene with its emotional muted undertones, as Qamrul Hasan has, and to that extent this vignette was the framing of a complete vision.

But the Qamrul Hasan I recall even more vividly is framed in my memory by the macabre events of riots and communal clashes of 1946, a year before the birth of Pakistan those pangs of frenzy which accompanied the approaching finale of the freedom movement in the sub-continent. The city was Calcutta: the time, August 1946, under the over-hang of communal frenzy. The city was splintered into isolated pockets cowering from the nightmare of impending extinction. Gone were the free and easy days of the cosmopolitanism of this second capital of the British Empire. The Muslim mohallas were overnight transformed into make-shift and inadequately-armed camps into which, day and night, poured thousands of badly frightened men, women and children, fleeing for their lives and in mortal dread of the uncertain future.

It was under the creeping shadow of these events, with the air reeking of violence and terror, that I met Qamrul Hasan for the first time.

Park-Circus was a predominantly Muslim middle-class area, with labour slums backing away from the modern apartments. But under the impact of the crisis, the lines of division had blurred and merged into one wide-awake community, mounting sleepless vigil against incursions of marauding bands, tending the sick and the wounded. A local Women's College had been turned into a first-aid post and hospital, and all able-bodied young men were trying to help out. It was while hurrying away with a bowl of blood-soaked bandages and rags to the dustbin that I saw a young man with a sketchpad and pencil crouching over a badly injured woman, lying with a hundred others in the corridor. He was an intriguing man with an athlete's figure showing through a brown khaddar bush shirt, his prize-fighter's broken nose, and his forehead creased with the tension of furrowed lines. No one could mistake him for a creative artist. Park-Circus was a predominantly Muslim middle-class area, with labour slums backing away from the modern apartments. But under the impact of the crisis, the lines of division had blurred and merged into one wide-awake community, mounting sleepless vigil against incursions of marauding bands, tending the sick and the wounded. A local Women's College had been turned into a first-aid post and hospital, and all able-bodied young men were trying to help out. It was while hurrying away with a bowl of blood-soaked bandages and rags to the dustbin that I saw a young man with a sketchpad and pencil crouching over a badly injured woman, lying with a hundred others in the corridor. He was an intriguing man with an athlete's figure showing through a brown khaddar bush shirt, his prize-fighter's broken nose, and his forehead creased with the tension of furrowed lines. No one could mistake him for a creative artist.

At first glance I took him to be one of the volunteers who in this emergency were doing yeomen service in rescuing trapped families from the riot-torn areas. But as the days and nights dragged on, we got to know each other better, though there was hardly any time in the first fortnight to sit back and discuss anything except exchange of the 'latest' from the city frontlines. In those days while we were jumping to the frantic bidding of distraught doctors and nurses and he was going out on frequent mercy-missions and filling out the remaining hours in feverishly sketching out the contours of the enveloping tragedy, our friendship ripened into the abiding comradeship of trench-mates.

Gradually I picked up the strands of his erratic life. How hard and bitter had been his struggle as a 16-year old to get into the Calcutta Art Institute in 1938; how, two years later, he had to desert his first love to eke out a living as a helping-hand to a professional doll-maker, how as he watched his master at work painting in Chinese lacquer the eyeballs, the eyelashes and the lips, he say the “featureless lump of baked clay come to life and realized for the first time the great power of art”, how three years of this apprenticeship and sweating at odd-jobs enabled him to go back to the Institute to complete his course of study.

Landscapes or urban life never attracted him very much. As he confided, “I have always been fascinated by the endless variety and suppleness of the human figure and form”. And herein lay his strength, his unalloyed and unimpeded contribution to contemporary art.

|

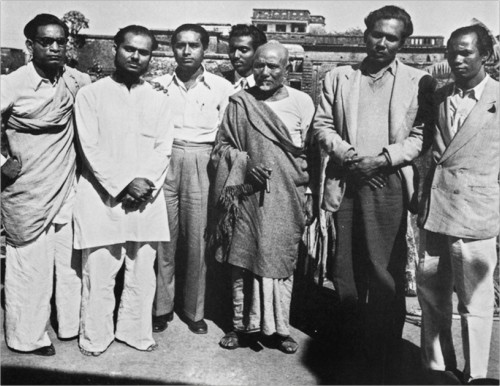

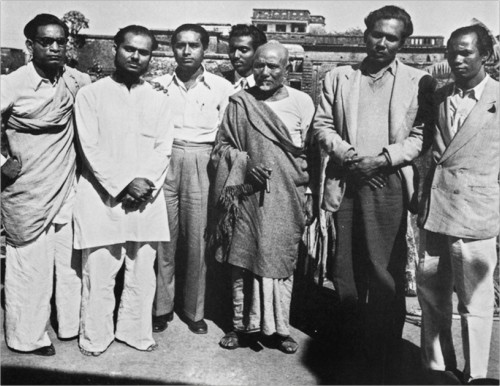

| Winter, 1955. In front of Bordhoman House Qamrul Hasan with Ustad Alauddin Khan, Ustad Khadem Hossain Khan, Shilpacharjo Jainul Abedin, Sardar Joinuddin and others in the music conference held in Dhaka. |

An oil, executed much later, comes to mind, a group of women bathing in the village pond under the heavy overhanging banana leaves, the sheen of luscious green impregnating the heavy languorous lower limbs and serpentine coils of the heavy-flowing tresses all captured in a muddy green flat monochrome. It was one of the earths earthy, showing the strong impress of the peasant-dolls sold in the market places during the weekly haats and melas.

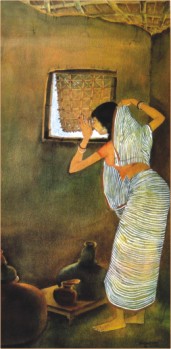

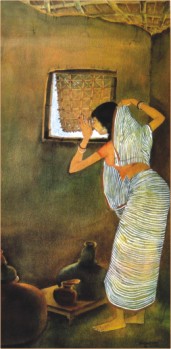

Years later, I saw a development of the same theme in his Toilet, exhibited in Karachi, where the woman's face was reduced to abstract planes and lines to emphasize the tension of a rough horn-comb entangled in the mesh of unruly hair, but the lower limbs still heavy with a sinuous eroticism.

His easy familiarity with the village doll-maker and artisan rooted in his intimate contact with the countryside as a member of the Bratachari Movement that, in the early forties, electrified the Bengal countryside with its voluntary self-help movement. There, among the hundreds of chanting teenagers clearing the water hyacinth and leveling the village roads, he found his own kith and kin, his spiritual brotherhood.

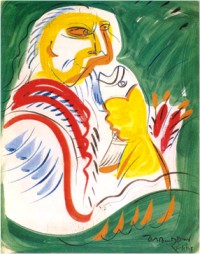

That is why there is nothing academic or sophisticated about his village women, the potter and the blacksmith, the cowherd and the snake charmer. He is part and parcel of the folk-tradition in art where figures are stylized, where pigments are loud and brash, where rhythms sway under the impetus of unabashed love and sex, and where primitive instincts are the motive force of life, framed by centuries-old traditions and code of behaviour.

In today's world of avant gardism, his is an anchored world of traditional life to which the simplest villager responds instinctively and the sophisticated shamefacedly, as if conscious of inherent inadequacies. He is not wedded to any theories of art because the wellsprings of his inspiration are his own people engaged, as he once put it, “in the fascinating task of day-to-day living”. He finds in the village painter and potter the same motif of realism and stylized abstraction which pours forth from his own brush; the same heavy and primary colours of the cloud-burst, and the sunset used by the peasant artist is found in Qamrul's palette.

Consciously or unconsciously, Qamrul Hasan has sought out and reinforced the folk content of the arts in Pakistan, and in this lies his strength as well as his weakness. He is par excellence the most faithful and yet the most imaginative painter of life as it is lived in the thousands of villages in East Pakistan. What lifts his themes from the stigma of narrow regionalism is the universal significance of life lived in the shadow of accepted faiths and beliefs, a life that stretches across the globe through the various continents.

|

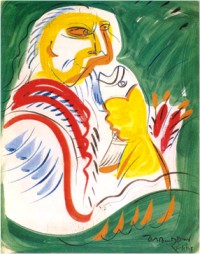

| Qamrul Hasan’s portrait by S K Afzal |

That is why his canvases have been acclaimed, both at home and abroad, as having the impress of a sincere and genuine sensibility working on a traditional mould, rendered significant by a unique vision. His women link up with the massive solidity of Man's earliest extant artwork, the Venus of Willendorf of the Stone Age and yet are as alive and contemporaneous as the village-maidens threshing rice in the mud-plastered courtyards of present day East Pakistan.

By being local, he is universal, for just as his female subjects remind one of the terracotta figurines of the facades of the temples of the Mainamati ruins, so do they recur in the one-anna dolls sold in the village marketplaces of his home province even today. Yet again, they are found in the princely court of Gautama, before he became Buddha, in distant Taxila!

In other words his human figures, in their varying postures, are the fertility totems of Man's earliest conception; they are the reaffirmation of the fundamentals of life as lived around the globe and through the millennia. They are veritably the “Roots of Heaven”, through which mundane beings aspire for, but never quite attain, the ideal.

Qamrul Hasan's paintings, even while during the middle-period developing on the lines of abstract patternism, never reached the stage of 'incomprehensibility' of some of his compatriots. For, he always related his work to the visual habits of the people, never straying too far from the observed. Yet he can never be mistaken for a folk painter, because he sees the visible universe from his individual and unique angle of vision, unconsciously rearranging things and even distorting them in accordance with an inner rhythm. One is even tempted to conclude that seeing man caught in the grip of hostile forces and an apathetic society, he creates totems out of human figures to impose his own vision of beauty, rhythm and harmony on a fragmented and inadequate life.

This is a reprint of an article written by S N Hashim for the Quarterly Magazine of Art and Architecture in 1967.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2009

|

|

Often reproached by the avant garde group of abstract painters for his anchored world of traditional vision, Qamrul Hasan emphasizes the folk element in art where figures are stylized, pigments are loud and brash, and primitive instincts are the motive force of life. The wellsprings of his inspiration are his own people engaged, as he puts it, “in the fascinating task of day-to-day living”.

Often reproached by the avant garde group of abstract painters for his anchored world of traditional vision, Qamrul Hasan emphasizes the folk element in art where figures are stylized, pigments are loud and brash, and primitive instincts are the motive force of life. The wellsprings of his inspiration are his own people engaged, as he puts it, “in the fascinating task of day-to-day living”. Park-Circus was a predominantly Muslim middle-class area, with labour slums backing away from the modern apartments. But under the impact of the crisis, the lines of division had blurred and merged into one wide-awake community, mounting sleepless vigil against incursions of marauding bands, tending the sick and the wounded. A local Women's College had been turned into a first-aid post and hospital, and all able-bodied young men were trying to help out. It was while hurrying away with a bowl of blood-soaked bandages and rags to the dustbin that I saw a young man with a sketchpad and pencil crouching over a badly injured woman, lying with a hundred others in the corridor. He was an intriguing man with an athlete's figure showing through a brown khaddar bush shirt, his prize-fighter's broken nose, and his forehead creased with the tension of furrowed lines. No one could mistake him for a creative artist.

Park-Circus was a predominantly Muslim middle-class area, with labour slums backing away from the modern apartments. But under the impact of the crisis, the lines of division had blurred and merged into one wide-awake community, mounting sleepless vigil against incursions of marauding bands, tending the sick and the wounded. A local Women's College had been turned into a first-aid post and hospital, and all able-bodied young men were trying to help out. It was while hurrying away with a bowl of blood-soaked bandages and rags to the dustbin that I saw a young man with a sketchpad and pencil crouching over a badly injured woman, lying with a hundred others in the corridor. He was an intriguing man with an athlete's figure showing through a brown khaddar bush shirt, his prize-fighter's broken nose, and his forehead creased with the tension of furrowed lines. No one could mistake him for a creative artist.