Inside

|

Notes to My Successor:

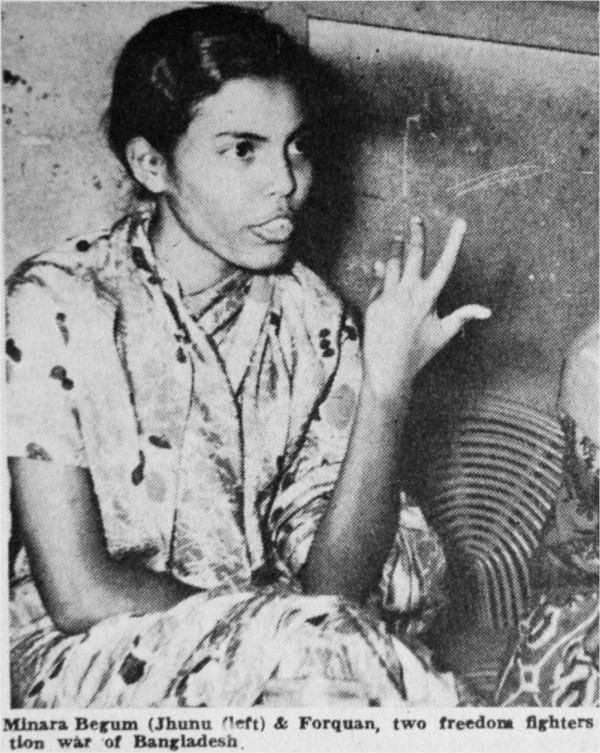

The Forgotten Women of the 1971 War

ZIAUDDIN CHOUDHURY recalls the contribution of brave women to the War of Liberation.

A time honoured tradition for civil servants working in the sub-divisions and the districts followed from the colonial days was to leave a confidential, "for your eyes only", write up for their successors in office. The write up would appear in a bound volume titled "Notes to My Successor", mostly hand written, that would contain the previous office holder's personal thoughts, experiences and travails that he had faced in the tasks of administering his domain -- be it a Sub-division or a District. The Notes would range from mere 10-12 pages to over a hundred, but these would contain valuable information on the area, particularly the places and personalities that the new person in the office would most likely visit and meet. In our times, this was a must read document that was secreted in the residential office of the Sub-divisional Officer (SDO) or the District Officer (titled Deputy Commissioner). There were many volumes of such Notes dating back several decades, which served as eye opening information on the area, warnings on things to expect, people to watch and do's and don'ts to avoid any mishap.

I worked as an SDO in two sub-divisions of then Dhaka district -- Munshiganj and Mankiganj -- in the most turbulent period of our national history. I was first appointed to Munshiganj as Sub-divisional Officer in February 1971, where I lasted till June. Toward the beginning of July I was transferred to Manikganj at the Army authorities' behest after a month long enquiry against me on my suspected role in March 1971. I had begun my Munshiganj stint as a twenty-something young civil servant hoping to put into practice what I had learnt in the training academy and from my seniors in the field. The political air was getting hot by that time with clouds looming over the future of the country. I plunged into my civil service career little realising that in a matter of weeks our country and people would be launched into the most traumatic and vicious war for survival, and I would be encountering atrocities and cruelties of the most horrific kind that would leave a deep scar on my young life. I had hoped that I would record my new found experiences in a new volume of Notes to My Successor, like many of my predecessors.

I worked as an SDO in two sub-divisions of then Dhaka district -- Munshiganj and Mankiganj -- in the most turbulent period of our national history. I was first appointed to Munshiganj as Sub-divisional Officer in February 1971, where I lasted till June. Toward the beginning of July I was transferred to Manikganj at the Army authorities' behest after a month long enquiry against me on my suspected role in March 1971. I had begun my Munshiganj stint as a twenty-something young civil servant hoping to put into practice what I had learnt in the training academy and from my seniors in the field. The political air was getting hot by that time with clouds looming over the future of the country. I plunged into my civil service career little realising that in a matter of weeks our country and people would be launched into the most traumatic and vicious war for survival, and I would be encountering atrocities and cruelties of the most horrific kind that would leave a deep scar on my young life. I had hoped that I would record my new found experiences in a new volume of Notes to My Successor, like many of my predecessors.

I could never write the Notes; the events moved too fast. Sudden turn of history and the traumatic happenings of the following months would fill me with so much despair that I never thought that I would be alive at all. I thought we were inexorably heading toward a disaster that would probably wipe us all out. As I moved with the events I also wondered what message I would leave for my successor. My predecessors had left Notes for the Successors to guide them for a future, a future both for the Successors and the people they would serve. These were advice on how to succeed in the job, how best to serve the people in the area. What message could I leave at a time when we were witnessing great death and destruction all around? How could I warn my successor against atrocities that would be unleashed against unarmed civilians by government-sponsored terrorists? What advice could I have for my successor when he finds himself a helpless witness to wanton mayhems, all in the name of saving the country by its self-appointed guardians? All I could have done was to leave a diary of those horror-stricken days, the sufferings of our people and my lament over my own fecklessness.

But this is not an account of the mayhem and atrocities that I would witness later in two sub-divisions. This is also not a narration of the brave resistance put up by our people in all walks of life during the torrid days of 1971. These Notes are a homily to that segment of our population that fought the same war, not in a frontal battle, but from behind, many times sacrificing their honour. These are our women, and the valiant ways they supported our war efforts sacrificing their honor, family and property.

Out of hundreds of thousands of these brave women, we have recognised only a few. Others have disappeared from our collective memory, unknown, unsung and unrecognised. We made some attempts to give some reparations to some of them for the indignities they suffered, but seldom have we made an attempt to record the valiant and death defying ways many of them worked to make our independence happen. This is a modest attempt at recounting a few of the valiant acts of our women during the torrid period when a marauding army was let loose on the villages of then East Pakistan.

The blitzkrieg with which the Pakistan Army attacked the civilian population on March 26, 1971 in the major cities of Bangladesh (then East Pakistan) did not reach my little sub-division of Munshiganj until about a few weeks later. I would see, however, the results of the havoc wrought by the Pakistan Army in Dhaka city and surrounding areas a week later when my motor launch anchored at Pagla Ghat. (The jetty was used as a harbour for all government-owned motor launches, including the famed Mary Anderson that was used by the Provincial Governor at that time.) Corpses floating in Buriganga river had choked the approach to the jetty in such a way that my launch operators had to use poles to steer the corpses away to anchor the launch. Half-burnt buildings and shops that were scenes of the recent rampage on my way to the Collectorate building gave the old city an eerie and almost surreal appearance. People of all ages and sex were still fleeing the desolate city in a panic mode clutching to whatever meagre belongings they could carry with them. As I moved along the ghost city I considered myself lucky, as Munshiganj had escaped the wrath of the Pakistan Army, at least up to that time. But it was only a matter of time that Munshiganj would be ushered into days of total mayhem and brutal operations that contingents of the Pakistan Army would unleash throughout nooks and crannies of the country.

The Army arrived in Munshiganj in early May of 1971 in a company of 100-plus soldiers led by a middle-aged Major from the Frontier Force. The company stayed in the subdivision for about six weeks. But it lost no time in terrorising the entire sub-division by torching villages, indiscriminate shooting of innocent civilians and arrest and disposal of young men suspected as freedom fighters. The Army routine included day "operations" in the adjacent thanas and villages and nightly sojourns in the relative safety of Munshiganj town.

As days passed, the little town of Munshiganj started to resemble a ghost settlement as majority of the dwellers left it for villages in the interior. A significant portion of this fleeing population were Hindu minorities as soon as they realised that they were the targets of random capture and later disposal by the Army. Munshiganj had a good number of this population at the time who belonged to the legal and business communities.

One afternoon the Army Major walked into my office and informed me that he had reports that a neighbouring village was harbouring a good number of "Hindu miscreants" with "arms". He said he had reports that the armed gangs were plotting to attack the army, and that it was necessary to sort the place out. I knew it was futile to plead with him without jeopardising my own safety; however, I suggested that his report be further verified by the police. He looked at me as though I had lost my mind!

My concern was also elsewhere. My second officer, a seasoned provincial service officer, was a Hindu. I had taken pains to keep him away from any possible encounter with the Pakistan Army, as we were already acquainted with the penchant of this murderous force to summarily dispose of members of the Hindu community, government official or not. A week after the arrival of the Army in Munshiganj, the officer had stated his intention to me to move to a nearby village where the town Hindus had congregated. He moved his family to this village even though I had warned him that moving to a predominantly Hindu village might not be a good idea. The army was more prone to attack such places in the pretext of miscreant cleansing, since according to the Pakistan Army, all Hindus were suspected "miscreants".

That night the village went up in smoke. Over a hundred houses were destroyed by the army in that operation. Ironically, a good number of the houses also belonged to Muslims. After all, fire cannot discriminate among houses based on religious persuasion of the owners. No one was spared. The army lobbed incendiary bombs into the houses, and brought out the occupants in droves. Sten guns fired randomly at fleeing people. The village was fully scorched, cleansed of the "miscreants"! I feared the worst for my Hindu officer and his family.

The next morning, like a miracle the second officer came to my bungalow, ashen-faced and unshaved for many days. With tears pouring down his face he narrated his escape from near death. Not only him but a dozen other Hindu families had also survived the catastrophe. And the person responsible for this heroic act was none other than his wife. His wife had gathered knowledge about this impending attack from a Muslim servant two days before the attack. She passed word to several families, assembled them in a common house the previous night and walked all night back to the town, safe and sound. She was the hero to the saved families! I could return the emotion only with more tears. Tears of joy that he was still alive.

The army would remain in Munshiganj for a total of six weeks during which the carnage in the villages would go unabated, some of which we would see, but others we would hear of much later. I myself was a subject of investigation by the army during the period, but in the end I was let off with a warning by the Major. (The main charge against me was that I had "allowed" the students to loot the armoury earlier in March and had attended a rally.) I was let off on condition of "good behaviour" and was asked to report to Dhaka Cantonment -- to the Battalion Commander -- every week, and be subject to questions on my conduct. I would do that for the next several weeks until I was reassigned to Manikganj Sub-division in July.

Unlike Munshiganj where the army was on a short mission, Mankiganj had a more permanent army presence. The local army commander, a Major, had the impressive designation of Sub-Zonal Martial Law Administrator, and as a civilian SDO (and Bengali to boot), I would be at his beck and call. He would call meetings at random at any time of the day or evening at his camp office, which was the local Dak Bungalow. In one such meeting I found also the Superintendent of Police of Dhaka, a Pakistani expatriate, who was also an ex-army officer. However, it was not the presence of the SP that surprised me; it was the presence of a young Bengali woman in the camp office with a small child sitting next to her. The Major jubilantly told me that the young woman was no other than the wife of an absconding miscreant, one Rabi Roy (not his real name), a suspected leader of the resistance force. The officer further informed me that Rabi's wife had volunteered to lead the army to the place of her husband's hiding.

This was news to me as I had heard from local sources that Rabi, an activist youth leader of Manikganj, had escaped with his family. I could not fathom how the army got hold of the wife, and why on earth she would volunteer to do such a thing! I tried to look at the woman in the eye, but she kept her gaze lowered avoiding my eye. The two officers present there discussed their plans with the young woman's volunteering effort since we discussed other matters affecting local administration. I departed with a disturbing thought that the woman was being kept there against her will and the price she must have paid already in the army camp.

This was news to me as I had heard from local sources that Rabi, an activist youth leader of Manikganj, had escaped with his family. I could not fathom how the army got hold of the wife, and why on earth she would volunteer to do such a thing! I tried to look at the woman in the eye, but she kept her gaze lowered avoiding my eye. The two officers present there discussed their plans with the young woman's volunteering effort since we discussed other matters affecting local administration. I departed with a disturbing thought that the woman was being kept there against her will and the price she must have paid already in the army camp.

Two days later there was one big raid by the army on a village in neighbouring Shivalaya thana with severe casualties on the army side. I myself saw wounded soldiers clambering out of a jeep in front of the Manikganj Jam-e-Masjid when returning from evening prayer. The story of the attacks and counterattack were revealed to me later by the Circle Inspector of Police.

Apparently the army contingent was told of a gathering of "miscreants" in the village by a "source" in its custody. However, as they approached the village they were surprised by a counterattack that took the army off guard. The counterattack came not from the village, but from country boats along the river firing on the convoy. The same source that gave the army the information also tipped off the other side. Fortunately, the retribution that the "source" suffered later from the Major was limited to her being incarcerated in the camp for a few more days as she pleaded total ignorance. Also the army officer had some second thoughts about summary disposal of the young woman -- she had been seen in the army camp by others including me. She was let off with her life, but not with her honour intact.

A few weeks after the Shivalaya attack the Manikganj Army commander decided to keep small para military contingents (the dreaded militia from Pakistan) stationed in two waterbound thanas of the sub-division instead of ferrying them from the sub-division. A contingent of about 30 people would remain in each thana for a month, and they would be replaced next month by a fresh contingent. In one such replacement in early August when a contingent was travelling to Saturia in an engine boat, it was fired upon by the guerrillas from the bushes along the river. There was no casualty, however, and the boat returned to Manikganj headquarters instead of proceeding toward Saturia.

The following day, the Armed Forces with reinforcement from Manikganj arrived at the village near the incident in large motor launches. They sprayed the village with machine guns, killed a large number of people by random shooting and of course burned houses as an additional punishment.

The army, having concluded the operation, thought they had secured the river route to Saturia, and sent the replacement contingent to Saturia the same route. As the motor launch carrying the contingent neared the same village, which was pillaged by the Pakistan Army a few days earlier, it received volleys of machine gun fire from freedom fighters, this time with greater intensity and accuracy. The suddenness and intensity of fire took the small army contingent by surprise and the operator of the launch lost control. The small boat capsized mid-stream with the hapless soldiers in the river, most of whom did not know how to swim. They managed somehow to hang on to the boat, which was floating and paddle ashore only to find themselves surrounded by angry villagers with machetes in hand -- their weapons of choice. None of the two dozen soldiers survived the wrath of the village.

The incident would have been one from a legion of attacks by the freedom fighters on the Pakistan Army had it not been due to the difference in the gender of the attackers. I was told by the Circle Officer of Saturia later that the gun shots from the river shore were meant to hit the launch operator and capsize the boat. The whole attack later was led by the women of the village who took upon the soldiers with whatever weapons they had in their hands. A revenge by the housewives of Saturia!

The incident would have been one from a legion of attacks by the freedom fighters on the Pakistan Army had it not been due to the difference in the gender of the attackers. I was told by the Circle Officer of Saturia later that the gun shots from the river shore were meant to hit the launch operator and capsize the boat. The whole attack later was led by the women of the village who took upon the soldiers with whatever weapons they had in their hands. A revenge by the housewives of Saturia!

The liberation war of 1971 was not fought in one sector or by trained soldiers and freedom fighters alone. Our freedom came because everyone in the country, across gender, religion and race, fought a common enemy and a common repression. As I have said before, these are Notes not necessarily to a Successor in Office, these are Notes of reminder to our succeeding generation on the pains, sufferings and tribulations that our people went through in the most turbulent period of our history. In particular these Notes are a salute to our women who sacrificed their blood, honour and dignity in support of their men -- husbands, sons, brothers. We may not have a repeat of another occupation army and a reprisal of the mad and ruthless acts of 1971. If there are any lessons learnt from these terrible days, they are that we as a nation can move forward only when we guarantee the basic respect for lives of all human beings and protection of rights across gender, religion and ethnicity.

Ziauddin Choudhury, a former Civil Servant in Bangladesh, works now for an international organisation in the USA. More incidents from the author's 1971 experiences in Munshiganj and Manikganj are recorded in his most recent book, Fight for Bangladesh: Remembrances of 1971 -- published by Xlibris, Bloomington, Indiana, USA.