Inside

|

Ban on Corporal Punishment in Upholding Rule of Law

ARAFAT HOSEN KHAN outlines cases of corporal punishment, the laws to prevent it and actions taken against it.

It may be true that the law cannot make a man love me, but it can keep him from lynching me, and I think that's pretty important.

--Martin Luther King, Jr.

The Bangladesh High Court has ruled that corporal punishment violates children's constitutional rights. This is definitely a positive step forward.

|

CARGO/GETTY IMAGES |

The incidences of corporal punishment in schools across the country are nothing new and the failure of the concerned authorities to comply with their statutory duties to investigate such allegations, or to prosecute and punish those responsible, and to ensure the security of children and their freedom from cruel, degrading and inhuman treatment and punishment while in school, in breach of their specific statutory duties as specified inter alia under the Regulations framed under Section 39(2)(XXIV) of the Intermediate and Secondary Education Ordinance 1961, and in violation of their fundamental rights as guaranteed under Articles 27, 31, 32 and 35.

Corporal punishment is defined as the deliberate infliction of pain as retribution for an offence, or for the purpose of disciplining or reforming a wrongdoer, or to deter attitudes or behaviour deemed unacceptable.

Corporal punishment can mainly be distinguished in two forms:

Parental or domestic corporal punishment: Within the family typically, children punished by parents or guardians;

School corporal punishment: Within schools, when students are punished by teachers or school administrators.

The practice of corporal punishment was recorded as early as 10th century BC in Míshlê Shlomoh, (Solomon's Proverbs), and it was certainly present in classical civilisations, being used in Greece, Rome, and Egypt for both judicial and educational discipline. Most of the earlier civilisations used heavy punishments as the means to maintain discipline and justice in their kingdoms. Heavy punishments were given to the wrongdoers in public so as to discourage others from doing the same. It worked well and people were scared of their ruling powers and generally peace reigned in all these civilisations.

But in the 18th century, when corporal punishment came to be confused with violence and brutality, the number of such punishments were reduced drastically. Then finally in the 20th century, corporal forms of punishment were totally abolished and banned in most areas of the world.

We now come to the 21st century, the century of terrorism, violence, brutality and killing of innocents, when we still want to resort to decent and supposedly civilised ways of punishing these inhuman crimes. We think it is inhuman to resort to any kind of harsh punishment.

Corporal punishment of children has very severe impacts on child development and growth. A report titled “Corporal Punishment in School in South Asia” published by UNICEF in 2001 states that corporal punishment inflicts psychological damage upon the child in addition to physical pain, and increases feelings of humiliation, anxiety, anger and vindictiveness in children. It has also been shown to reduce a child's sense of self worth and to increase his/her vulnerability to depression. Corporal punishment also results in permanent interference with children's education and may become a direct reason for children dropping out of school, as increased anxiety levels cause a loss of concentration and poor training. Children subjected to corporal punishment have also shown aversion to taking risks and being creative.

However, the good news is Bangladesh is now the 110th country to ban corporal punishment in schools and ensure that children are taught in an environment that fosters curiosity and confidence as well as a culture of peace and violence and this has taken place via a writ petition filed on 18.07.2010 in the public interest by two petitioners, BLAST and ASK, challenging the systematic failure of the state to take action to investigate serious allegations of corporal punishment in primary and secondary educational institutions and madrasas, or to prevent further such incidents.

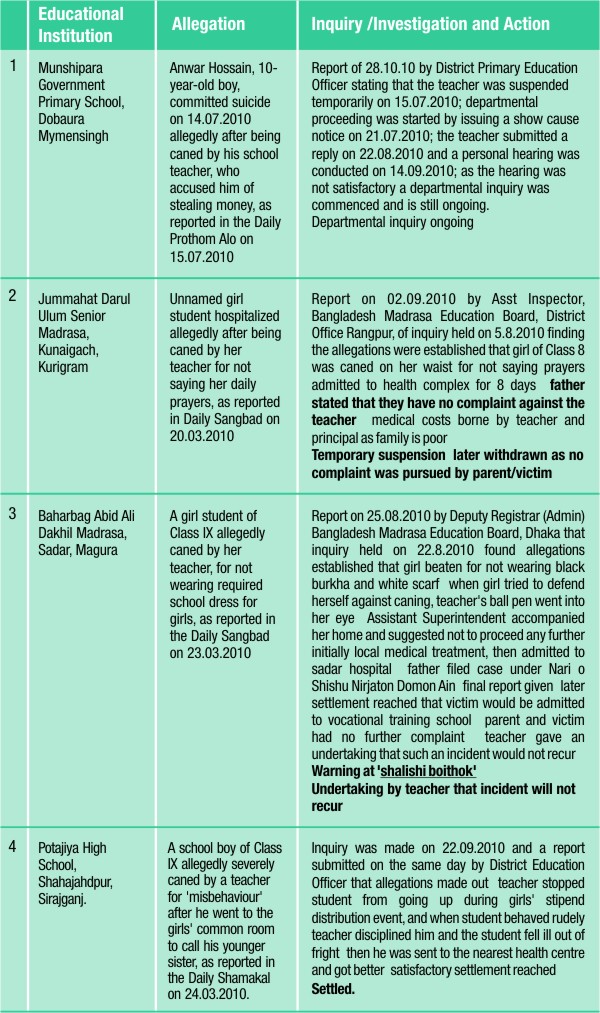

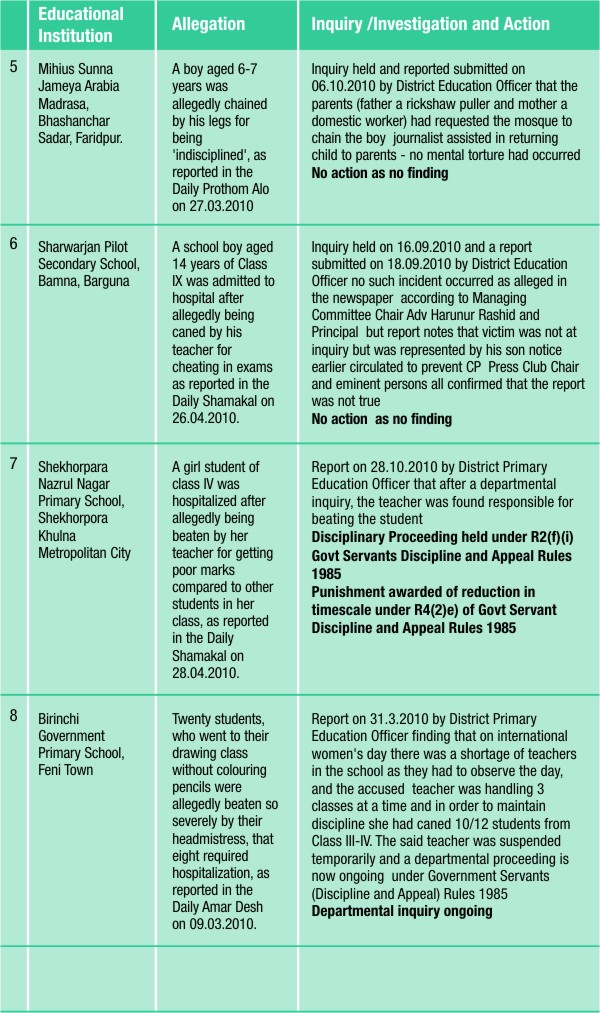

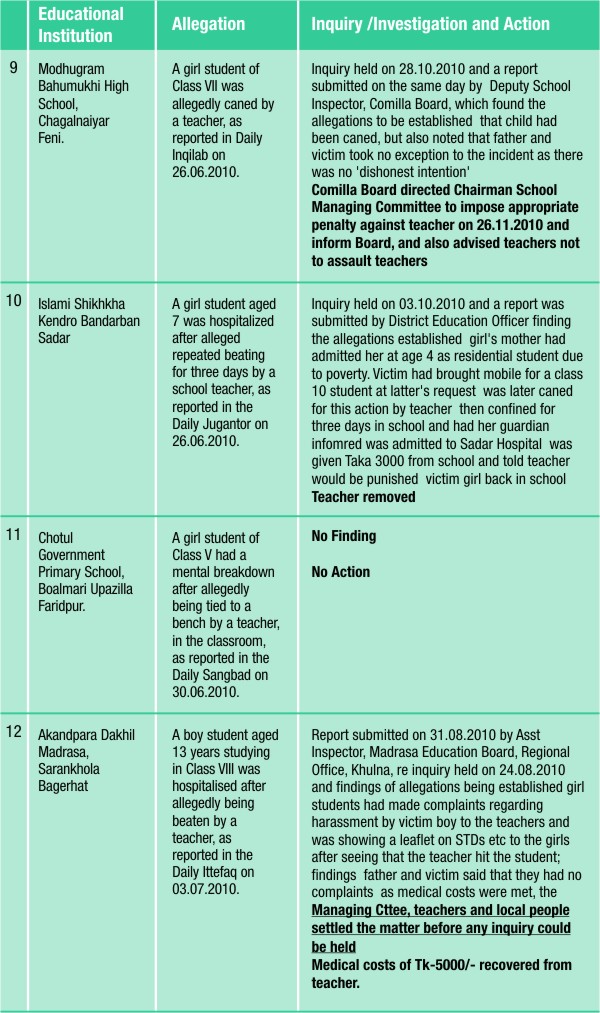

The writ followed reports of 14 separate incidents between March to July 2010 of caning, beating and chaining of boys and girls by teachers, culminating in the suicide of a 10-year-old boy following a reported beating at school.

On 18.7.2010, the Hon'ble Court issued a Rule upon the Government and finally on January 13, 2011 the High Court Divisional bench comprising Justice Md Imman Ali and Justice Md Sheikh Hasan Arif delivered a judgment where they held that corporal punishment constitutes a clear violation of children's fundamental rights to life, liberty and freedom from cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment. It held that the Government had failed to take appropriate and adequate action to investigate or take either preventive or punitive action in specific incidents of corporal punishment against children in schools and madrasahs, including that involving the suicide of a 10-year-old boy, and others involving caning, beating, chaining by the legs, forcible cutting of hair and confinement. The Court referred to the Government's obligations under national and international law, including Articles 27, 31, 32 and 35 of the Constitution, the Child Rights Convention and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, to prohibit, prevent and prosecute such acts.

The Court also issued directives as appropriate on the concerned Ministries (Education, Primary and Mass Education, Home Affairs and Women and Children's Affairs) and Boards of Education (1) to disseminate and implement the final guidelines on prohibition of corporal punishment as framed by the Government; (2) to incorporate the imposition of corporal punishment into the definition of 'misconduct' applicable to teachers of government-run educational institutions under existing laws, including the Government Servants Discipline and Appeal Rules 1985, and to take appropriate action against teachers responsible for corporal punishment; (3) to ensure that inspections of schools and madrasas address whether complaints of corporal punishment have been made, investigations done, actions taken against those responsible, and/or any preventive measures adopted; (4) to ensure that inquiries into such allegations must be confidential and ensure security of the victim; (5) to provide teacher training on 'safe, effective and proportionate means to discipline children'; (6) to establish a High-level National Monitoring Committee with Secretaries of the concerned Ministries, and including an independent member with a track record in protecting human rights, to monitor actions taken in compliance with the Directives; (7) to establish district-level Monitoring Committees under the Deputy Commissioner , to monitor actions taken to comply with the directives; (8) to disseminate information through the national media, including private broadcasters, on corporal punishment as a wrong and human rights violation and (9) the Court also directed the Government and the High-level National Monitoring Committee to report to the Hon'ble Court regarding action taken in compliance with the Rule.

However, worries remain if we analyse the entire case more closely and think about whether this landmark judgment will actually protect children's rights.

The said writ petition was filed on the basis of continued and unchecked incidences of corporal punishment meted out to children in primary and secondary educational institutions, of which some of the most recent reports were published in national newspapers. When it was moved before the Hon'ble Court, the Court issued a rule upon the Government to report to the Court on whether due investigations were held and actions taken against the instances of corporal punishment. It would be good to mention that the Government and the Ministry of Education were really helpful and co-operative in the court proceedings in order to dispose of this matter effectively and positively. They had, in compliance with the Court's orders among others, issued a Circular dated 9.8.2010 prohibiting corporal punishment and requiring action to be taken by teachers; sent a memo directing investigations into the incidents brought to the Court's attention; held an inter-ministerial Meeting on 29.8.2010 to frame Guidelines on corporal punishment.

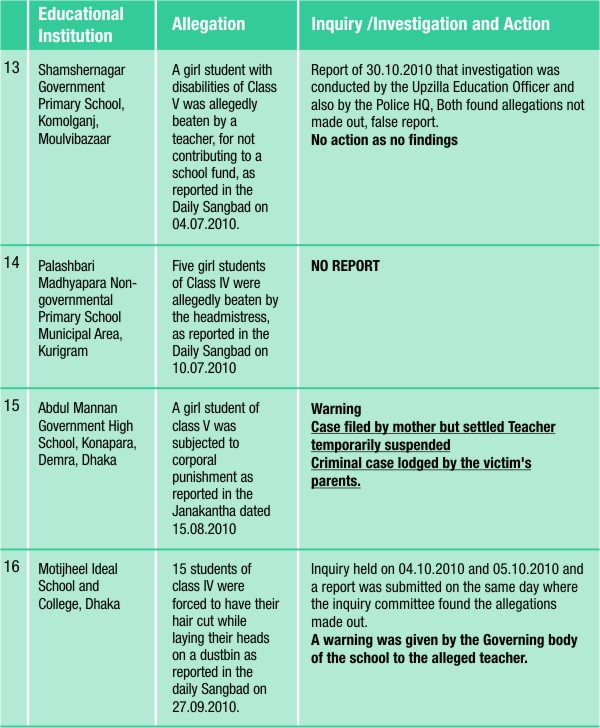

Below are incidents of corporal punishment as reported in newspapers, and, in compliance with court orders, descriptions of investigation reports as well as the action taken against teachers who were responsible for corporal punishment:

On close examination of the above table, it becomes apparent that the victims' voices are absent and that the parents' concerns are emphasised. More surprisingly, most of the matters were disposed of by settlement by way of “shalish” or arbitration. How possible or effective is to establish rule of law under such circumstances, we may ask.

|

MICHAEL DINO HENDERSON/GETTY IMAGES |

It is also noticeable that none of these forms of behaviour by children involve the commission of any kind of offence recognised by criminal law. While certain behaviours, for example, 'not paying attention' may well involve an offence for which a child may be disciplined, there is no law which authorises the imposition of caning, beating, being chained or confined or any other form of corporal punishment.

Not only that, the punishments meted out to children in educational institutions in the name of 'discipline or control' may themselves constitute criminal offences under existing laws including the Bangladesh Penal Code 1860 and the Children Act, 1974 as well as the Nari o Shishu Nirjaton Domon Ain (Bishesh Bidhan) Ain 2000 (as amended in 2003).

The settlement of these cases through arbitration instead of in court is unacceptable under the judicial system. If such practices continue by the concerned authorities, we will never have an effective judiciary and in turn rule of law will never be established in our country and we will not see the true light of democracy.

In order to have an effective judiciary and to establish rule of law, we all have to avoid interpreting the law. We all have to work together to enforce them -- vigorously, without regional bias or political slant. We all need to cultivate the intentions to do the right thing. But all the noble mentions of the aforesaid judgments, all the high-sounding writings about liberty and justice, are meaningless unless people, we, breathe meaning and force into them. For our liberties depend upon our respect for the judiciary.

The road ahead is full of difficulties and discomfort. But we should welcome the challenges and also we should welcome the opportunity that has been created by the judiciary and we all should pledge our best efforts. We want to see the establishment of freedom and our children growing up under the rule of law where their rights would be protected.

Arafat Hosen Khan is Barrister-at-Law, The Honorable Society of Lincoln's Inn and with Dr. Kamal Hossain and Associates. He can be reached at barrister.arafat.h.khan@gmail.com.