Inside

|

Justice Now Tazreena Sajjad outlines the lessons Bangladesh can draw from Cambodia in bringing war criminals to trail.

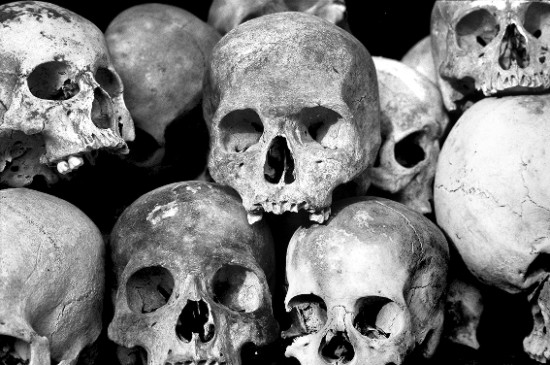

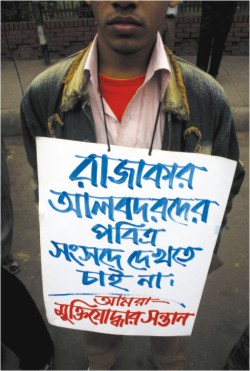

Between 1975 and 1979, Cambodia was under the rule of the Khmer Rouge. Led by Pol Pot, the goal of the Khmer Rouge was to reconstruct Cambodia on the communist model of Mao's China and create a classless society comprising of one federation of collective farms. This radical program included isolating the country from foreign influence, closing schools, universities, hospitals and factories, abolishing banking, finance and currency, outlawing all religions, confiscating all private property and relocating people from urban areas to collective farms where forced labour was widespread. It also included abolishing all civil and political rights, enforced separation of children from their parents, and the systematic killing of lawyers, doctors, teachers, engineers, scientists and professionals in any field (including the military) along with their extended families. Leading Buddhist monks were killed and almost all temples destroyed. Also targeted were minority groups, victims of the Khmer Rouge's racism. These included ethnic Chinese, Vietnamese and Thai, and also Cambodians with Chinese, Vietnamese or Thai ancestry. Half the Cham Muslim population and 8,000 Christians were also murdered. Music and radio sets were banned. It was possible for people to be shot simply for knowing a foreign language, wearing glasses, laughing, or crying. One Khmer slogan ran ''To spare you is no profit, to destroy you is no loss.'' It is estimated that approximately 2 million Cambodians died during Khmer Rouge reign from executions, disease and starvation. While Bangladesh experienced political instability, dictatorships and military coup d'états and the entrenchment of alleged war criminals in public spaces, Cambodia struggled with a civil war following the overthrow of the Khmer Rouge, a regime dependant on neighbouring Vietnam, and continued power struggles between different political parties till the formal surrender of the remaining Khmer Rouge forces in 1998. The discussion of accountability for the genocide was as absent in mainstream discourse in Cambodia as in Bangladesh. There were, however, a few attempts to seek justice for the genocide and crimes against humanity that were committed during Pol Pot's rule that merit mention. First, a memorial and museum in Phnom Penh were erected and a day of remembrance was established on the date of Khmer Rouge's overthrow. Second, seven months after the overthrow of Khmer Rouge in 1979, a "People's Revolutionary Tribunal" was established, staffed with Cambodian and international lawyers that convicted Pol Pot and Ieng Sary of genocide in absentia. Ieng Sary received a royal pardon in 1996 for his defection to the government and Pol Pot died in 1998 shortly after being put under house arrest. However, the trial was considered mostly a show trial, and did not satisfy the demands for justice and accountability amongst the human rights community in the country. Although the 1991 Paris Peace Accords contained no explicit provision for justice or accountability, the parties committed "to take effective measures to ensure that the policies and practices of the past shall never be allowed to return."1 The idea of the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) was initiated in 1997, when Cambodian co-Prime Ministers Hun Sen and Norodom Ranrindh wrote to the United Nations to request assistance in providing accountability for senior Khmer Rouge Leaders that were still at large. A UN commission of experts explored various options for pressing criminal charges and finally recommended that trials be held under international guidance, preferably outside the country. This resulted in a protracted period of negotiations that lasted nearly ten years before the inauguration of the court in June 2006. The June 2003 Agreement between the UN and the Royal Government of Cambodia established that the ECCC procedures shall follow Cambodian law, and the ECCC "shall exercise jurisdiction in accordance to international standards of justice, fairness, and due process of law as set out in Articles 14 and 15 of the 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights" to which Cambodia is a state party.2 Under Article 28 of the agreement, the United Nations reserves the right to withdraw cooperation from the process if Cambodia causes the ECCC to fall short of complying with those standards. Under the final terms of the agreement, the ECCC is a hybrid international tribunal that is composed of both Cambodian and international judges, prosecutors and court staff with the mandate to prosecute "senior leaders" of the Khmer Rouge and those "most responsible"for crimes against humanity, war crimes, genocide and violations international humanitarian law and certain crimes under national law committed between April 17, 1975 and January 6, 1979. The majority of the judges are Cambodian, but it is required that at least one international judge must agree to any verdict. This unique arrangement ensured the primacy of Cambodia's sovereignty without compromising compliance with international norms and standards. And although it has not yet been finalised, the court statute includes the mechanism to provide non-monetary compensation to victims who may participate in trials. The selection criteria has pragmatic underpinningsit allows for some discretion of the court as to the number of perpetrators that will be prosecuted while recognising that the there will perhaps be no more than ten defendants. There is also the concern that spreading the net far and wide could lead to a "witch hunt" of junior Khmer Rouge leaders that do have links to the existing government. Finally, there is the financial concernthe court's budget of $56 million spread over three years would not be able to accommodate more than a handful of trials. To date, the ECCC has arrested all five Khmer Rouge leaders indicted by both Cambodian and international prosecutors. These figures have been charged with various counts of war crimes, crimes against humanity, murder, torture and genocide. The challenges for successful prosecutions are significant. There are logistical and procedural delays with serious allegations of political interference and corruption. There is always a niggling concern that the government can disrupt or derail trials to suit perceived political needs and because a majority of Cambodian judges will hear cases and the Cambodian prosecutor and investigating judge must concur with any trial decisions. There are other challenges to consider--administrative hurdles from finishing the courtroom preparations, hiring translators, implementing financial controls to prevent corruption and the urgent need of funding. The ECCC will soon seek an additional $43 million to fulfill its mandate. There too is a lack of clear resolution of the appropriate response to allegations of corruption within the Cambodian side of the court. There are allegations of a kickback scheme in which employees are permanently obliged to pay a proportion of their salary to their superiors in exchange for their recruitment. Those who have lodged complaints against these practices have allegedly lost their jobs as a direct result. While the ECCC's Cambodian administration has consistently denied these allegations, the persistence of these allegations and the willingness of some staff to publicly make these statements have done damage to ECCC's legitimacy. Lessons for Bangladesh First, Bangladesh is not alone in experiencing the moral and political pressure to respond to war crimes committed in the 1970s. Second, like Cambodia, Bangladesh has to respond to legal obligations that state there is no statute of limitations (i.e. there is no statute setting a time limit on legal action) in the event of systematic and widespread abuses committed against a people. Third, the passage of time has had a detrimental impact on pragmatic issues such as loss of witnesses, documentation of crimes and the entrenchment of war criminals in the public sphere. That could pose challenges to judicial proceedings that at times could be difficult if not impossible to circumvent. Fourth, in the discussion of what kind of trials, and the extent of international intervention and support, there will be inevitable concerns raised about sovereignty and pressures to ensure that it is a fully domestic led effort. Correspondingly, these will also raise questions about the independent nature of the proceedings and could engender speculation of negative external intervention and interference and give rise to rumors and allegations of "foreign" manipulation in the outcomes of the cases. On the other hand, as experiences in Cambodia have indicated, a domestic led effort is open to both allegations and realities of corruption both in the legal and particularly in the administrative departments of the ECCC. The possibility of such discussions emerging in the Bangladesh context and the politicisation of

legal proceedings would have to be guarded against. While the Cambodian efforts for seeking accountability have received a significant level of international support, both in terms of expertise as well as financial assistance, Bangladesh has to be acutely aware of the extent to which the international community will be allowed to and be willing to participate in its domestic efforts and perhaps even more importantly bear the financial burdens of these trials. The costs of war crimes tribunals are not minimal; outside of the immediate court costs, there will be additional administrative and bureaucratic costs especially in the case of prolonged trials and it is critical to identify potential donors and funds in the event of such a reality. There are other lessons that Bangladesh can draw from Cambodia and particularly from the ECCC. First, there is no substitute for coordinated, organised and well-developed documentation procedures and a unified stance that will continue to put pressure for the war crimes trials to move forward while upholding the highest standards of justice. The Cambodian Documentation project has done a remarkable job in tracing, tracking and collecting evidence of the genocide and its network of NGOs have played a critical role in ensuring that decades after the commission of crimes, individuals are held responsible for their roles in human atrocities and that the government makes a firm and sustained commitment to dealing with those guilty of war crimes. Bangladesh NGOs, human rights activists and individuals pushing for the war crimes trials need to pay attention to the organisation and commitment demonstrated by those in Cambodia who have made ECCC possible and learn from both their strategies and their mistakes. Second, while there are those who criticise the ECCC and are cynical of the proceedings, what is irrefutable is the discourse that is developing in Cambodia regarding its dark history and a growing sense of awareness of the need to know more and engage with those who have survived the genocide in the 1970s. In Bangladesh, a similar strain is already visible; yet it is critical to ensure that urgency and awareness is allowed to grow, develop and sustain itself so that the history of the country is neither forgotten nor allowed to be sabotaged by revisionists' interpretation of the events that led up to 1971. The ECCC judges' decisions to adopt rules allowing victims to participate as civil parties in the proceedings and to create a dedicated victims' unit has been a positive development for the ECCC's legacy within Cambodia and also a precedent for other internationally assisted courts. In areas such as witness protection, court management practices, provision of transcripts of hearings, and an independent defence support unit that works with defence legal teams, the ECCC have also taken important steps towards modeling a functioning, fair judicial system. Those responsible for the Bangladeshi war crimes trials have much to learn from these developments. Further, the ECCC has also provided a useful way for civil society to publicise the trails and has begun to promote the public and media to reflect on Cambodia's history. Court officials have participated in public outreach events, the Cambodian nongovermmental organisations such as the centre for Social Development and Khmer Institute of Democracy and ADHOC have been active in developing a range of public for a and reconciliation exercises. Although the scale of the war crimes trial in Bangladesh will be different, it is pertinent to take note of the various ways in which the ECCC has been actively engaged with the Cambodian public to disseminate information about its work and the reasons for its establishment while creating new venues for civil society to engage with court proceedings and outcomes. If such measures are completely disregarded in the Bangladesh context, then the trials will remain a remote and isolated project without context and without continued public support and interest in the proceedings and its outcome. While Bangladesh and Cambodia share a history of human tragedy that unfolded around the same time and overshadowed by Cold War politics, international indifference, domestic politics and policies and the subsequent entrenched climate of impunity, both countries already have and will continue to have distinctly different experiences in trying to address questions of war time atrocities. International support and nature of the trials in Cambodia is different from the Bangladesh context as is the reality of the length of trials and the practical considerations surrounding trials of the elderly war criminals in the Cambodian situation. There are other differing aspects too, such as the confessions of the born-again Christian Duch whose statements have provided a breakthrough for the ECCC to continue to press forward on seeking prosecutions of other criminals for the Cambodian genocide.

Nevertheless, as pointed out earlier, there are valuable lessons to be drawn from our Asian neighbour which is of vital significance for the success of the Bangladeshi trials. While we may not witness full disclosures and confessions brought on by remorse and guilt of perpetrators, a vigilant, systematic and vigorous process can hope to identify and try individuals guilty of committing egregious crimes. The reality is, like the ECCC, the war crimes tribunal will be largely symbolic in its ability to try a handful of cases against the worst perpetrators; yet, if the groundwork is prepared adequately, justice can be served against those who have yet to face charges for crimes against humanity. The ECCC's experience has already indicated that corruption and political manipulation is a reality even with international presence; in the Bangladesh context, such a lesson should promote steps to affirm the independence of such a court and barring government officials from actions that could be perceived as attempts to influence the judicial process. Individuals implicated in corruption charges should be fully investigated and removed if the charges rove to be true. Last, but not the least, one of the challenges facing the ECCC is the lack of clarity regarding the discussion of reparations for victims. The ECCC is being advised to consider how to maximise the impact of the reparations mandate, including soliciting public input on the feasibility of a trust fund for victims and relevant cultural considerations in formulating appropriate collective reparations for the various categories of victims involved. In the case of the war crimes trials in Bangladesh, deliberations regarding reparations should not be left as a marginal issue; if, like Cambodia there is lack of clarification of what reparations should involve, there is a strong possibility that the Bangladesh war crimes trials will face a challenge of monumental proportions. Additional Readings: An Anatomy of the Extraordinary Chambers." Awaiting Justice: Essays on Khmer Rouge Accountability, Jason Abrams, Jaya Ramji & Beth Van Schaack (eds.) (Mellon Press, 2005). 1 Agreement on a Comprehensive Political Settlement of the Cambodian Conflict, Article 15(2) (a) Oct 23, 1991. Tazreena Sajjad is a member of the Drishtipat Writers Collective. Her doctoral research examines the impact of war criminals in political processes in post conflict contexts.

|