Inside

|

How Devolution Can Change Our Politics Jyoti Rahman examines the benefits of spreading out political power

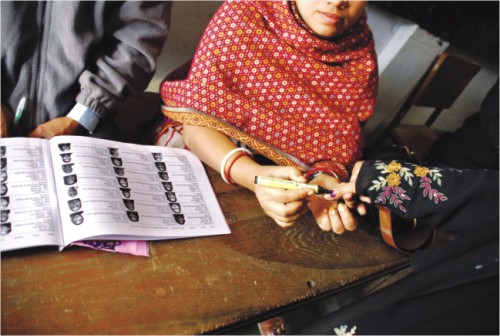

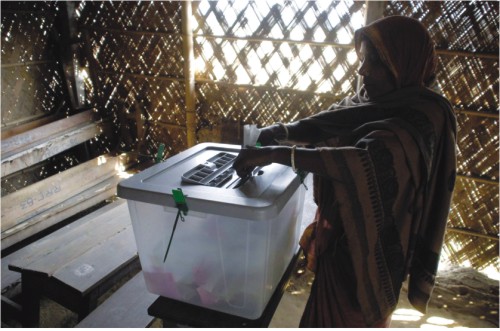

A few weeks after the parliamentary election, elections were held for upazila councils across the country on January 22. Awami League swept both. But the former has been hailed for its peaceful lead up and the festive atmosphere, whereas the latter was characterised by significant irregularities. Unsurprisingly, commentaries since the upazila election have focussed on these irregularities. But this has meant some important questions have remained relatively unexplored. It is not yet clear exactly what these councils will do. What will they be responsible for? What authority will they have? What will be their relationship with the local MPs? Media speculation abounds, but at the time of writing, answers are not clear. And barring a few exceptions, most of the civil society voices that championed political reform during the last elected government and the regime that followed are relatively silent about what these councils should do. This is quite surprising given the possible impacts these elected local bodies can have on our politics. This brings us to the question this article asks: How can the upazila system, or devolution more broadly, change our politics? By devolution I mean elected local governments (district, municipal, upazila, union councils) with wide ranging responsibilities resulting in a devolution of political power from Dhaka to the local levels. Devolution is distinct from delegation in that the former involves permanent empowerment of local bodies, whereas the latter involves the power residing in the central government.1 In Bangladesh, successive governments have attempted delegation through creating new institutions, but earnest devolution has never been attempted. And yet, devolution can significantly strengthen our democratic evolution in the long run, even as it throws up challenges and setbacks in the short turn. H.M. Ershad brought in the upazila system in the early 1980s, whereby considerable authority and responsibility were given to directly elected upazila councils. Like everything else associated with the fallen dictator, the upazila councils, and the devolution project as such, lacked legitimacy with our political and opinion-making class in the early 1990s, and the second BNP government dissolved the system. While the democratic credentials of the Ershad-era upazila councils are questionable at best in practice, in theory that experiment was the strongest step we took towards devolution. As such, it is worth noting how the system was intended to work. Under that system, functions at the upazila level were divided into two categories: "retained" and "transferred." The regulatory functions and major development activities of national scope were retained by the national government at the upazila level. These functions included maintenance of law and order, civil and criminal judiciary, and the administration and management of central revenues. Functions transferred to the upazila councils included planning, promotion and execution of development programs, primary education, health and family welfare, various rural infrastructure programs, and any other functions that could be carried out at the local level. In the late 1980s, the chief government official in charge of local projects and development efforts was the upazila nirbahi officer (UNO) who managed a staff of about 250 technical and administrative officers. The UNOs were Bangladesh Civil Service officers, but their direct supervisors were the popularly elected chairs of the upazila councils. The councils were to plan for public works and development projects, which the UNO and its staff would implement.

The second AL government revived the system, but neither party held upazila elections, even though both promised them in the 2001 election. While upazila councils have been elected, at the time of writing, the extent of devolution is very uncertain. Instead of speculating on what the government will (have) decide(d) in this regard, let's discuss how these councils (and their counterparts in other local bodies) could affect our politics. How Devolution Can Strengthen our Democracy Devolution leads to increased accountability. If an elected chairman does not do his or her job well, they can be reproached immediately. For example, any elected chairman or councillor who finds himself embroiled in a fertiliser or seed disbursement scandal will find it very hard to hide from his or her voters -- unlike MPs, local chairmen or councillors seldom have the luxury of living in Dhaka. Devolution will strengthen democratic performance of both the elected representatives and the voters and the population at large. Local panchayats in the Indian state of Kerala, for example, are famous for their debates, during which people gather around in the evening and ask questions to their local elected leaders about different projects. While initially these debates can be timid, over time people ask hard questions such as how funds may be disbursed or why tenders are offered to some particular bids. As the local people get involved in deliberations, democracy is strengthened qualitatively. Indeed, despite many irregularities, this has begun with the January 22 upazila election. Let me cite just two examples. In Debidwar, a western-educated scion of a locally influential family was elected for his battle against a phensydil epidemic gripping the local youth. Meanwhile, voters in Phulbari elected one of the organisers of the 2005 popular uprising. To be sure, absent devolution, a new leadership will still arise. But devolution will allow heroes of Kansat or Phulbari their rightful place in running this people's republic of ours through democratic means, whereas without it, local frustration will be channelled through figures like Bangla Bhai. Devolution will allow for peaceful co-existence by ending winner-takes-all politics. Talukder Maniruzzaman ended his "The Bangladesh Revolution and Its Aftermath" with this sentence: That book was first published in 1980. Over a quarter-century later, our winner-takes-all political system, and not the personalities of the current and former prime ministers, corruption, or some ridiculous notion of national shortcomings, was the fundamental reason behind the political crisis that led to 1/11.4 Under that system, the winning side had a monopoly over everything from Bangabhaban to the local cricket club for five years. The first elected government realised this only towards the end of its term. The second one tried to make the most of it. The third one took it to an art form, nearly tearing apart the very fabric of our body politic in the process. What will happen now that democracy has been restored?

Consider this. BNP received about 32% of votes cast in December 2008, compared with 31% received in February 1991. The most effective way of giving BNP a stake in governance, and honouring the third or so of our people who support its politics, is through devolution. And five or 10 years from now, when the political tide turns and AL finds itself on the left of the Speaker in parliament, devolution will allow it to run a significant number or upazila or city councils. Devolution will change the debate from being one about a Dhanmondi vs Banani horse race to something that includes the farmer, the landless, the small trader, and the mofussil dwellers.5 Can one think of a more effective way of ensuring the debate changes than having grass root politicians with executive experience in running local governments? Arguments Against Devolution At this point, we need to note the power of vested interest against devolution. From Sheikh Mujib to the powers-that-be behind the last regime, every government in our history, elected or otherwise, regardless of their ideological mooring, has been aware of the power of our bureaucrats. Gen. Ershad and Mrs. Zia learnt the hard way that it is impossible to stay in power without the support of the bureaucracy. And while the anti-corruption revolutionaries of the last regime threw the most powerful politicians in jail, the bureaucracy remained essentially untouched. Therefore, we shouldn't be under any illusion that devolution can be paid for by taking on the bureaucracy. However, if devolution does take hold, and power is transferred to elected local politicians from unelected bureaucrats, in time that will allow for more efficient, transparent, and democratic governance. As such, devolution is well worth the financial cost. Devolution will diminish powers of MPs. This was the argument of Nazmul Huda, who headed a committee on the issue during the second BNP government. While this is true, this is probably a good thing. What is a typical MP in the current system expected to do? He (and sometimes she) is expected to beef-barrel. His re-election is dependent on how many culverts are built, how many mosques have been renovated, how the relief has been distributed, or how the fertilisers have been disbursed. He gets to have a say in the local schools, libraries, and cultural functions. I've been told by a former MP, he has to arbitrate (salish) on disputes including marital problems. Devolution will mean that the local MP will lose much of these powers to the chairman and councillors. But the flipside of this is that devolution allows MPs scope to focus more on national legislative issues and on representing the constituency's interests at the national level. One of the most laudable steps taken by the new government towards changing our political culture is the creation of parliamentary committees in the parliament's first session. However, as long as the MPs' re-election depends on disbursement of wheat and fertiliser, they will not focus on the committee work that lies at the core of democratic checks and balances.6 Devolution will lead to a better set of local executives and national legislators, both representing the popular will. Further, it is not necessarily the case that devolution will mean no role for the MP in local affairs. Whether in advisory or supervisory capacity, MPs should have a role in local affairs. This will help create a political culture of peaceful co-existence when MPs and chairmen come from different parties. Undoubtedly the transition will be difficult to manage for the politicians. It will probably take a newer cohort of politicians to work out a workable system. But the process can only strengthen our democratic evolution. Devolution will lead to further criminalisation of politics. We have already seen how the January upazila election was more violent than the December parliamentary one. Last year's local government elections in West Bengal -- with a far stronger democratic tradition than ours -- saw serious violence. Plus, there is a real concern that at least initially, the elected councils will discriminate grossly against the members of the opposing party and there will be rampant corruption. However, any argument against devolution based on "undesirable people might get elected" is really an argument against democracy as such. Our voters have repeatedly kicked out failed leaders at the national level. There is no reason to think that it will be any different at the local level. Devolution will strengthen "reactionary" policies. Of all the general arguments against devolution, this is perhaps the most serious. Winning chairmanship in 20 upazilas (out of 479), Jamaat-e-Islami did a lot better in the local election than the national one, where it won only 2 seats (out of 300). It is quite possible that these chairmen will try to institute a range of reactionary social policies. For example, an Islamist-controlled upazila council could ban music (as happened in parts of Pakistan where Islamists won provincial government) or stop women from walking alone after dark (as happened in parts of Indonesia after Islamists won local councils). However, voters are the best judge. In Pakistan, Islamists were voted out of power because they concentrated more on banning music than running the provinces. Why should it be any different in our upazilas? And far more importantly, liberal-progressives need to convince the majority of the merits of their values -- enforcing these values from seminar rooms or courts in Dhaka don't work. Concluding Comments This piece has argued that devolution will strengthen our democratic evolution. Despite many irregularities, the upazila election has been a step towards the right direction. It will take a while before a working relationship is established between the upazila councils, MPs, and the bureaucracy. Undoubtedly there will be hiccups, just as there will be hiccups in our quest for a better functioning parliament. But just as we would oppose any attempt at reverting to unelected rule, so should the democratic voices oppose any attempt at reverting the process of devolution that started with the January 22 election. Jyoti Rahman is a blogger (www.jrahman.wordpress.com) and a member of Drishtipat Writers' Collective. He can be contacted at dpwriters@drishtipat.org. 1. For a detailed discussion, see Ahmed T., Local Government and Local Governance: Issues and Challenges, Daily Star 18th Anniversary Supplement, Feb 2008. |