Inside

|

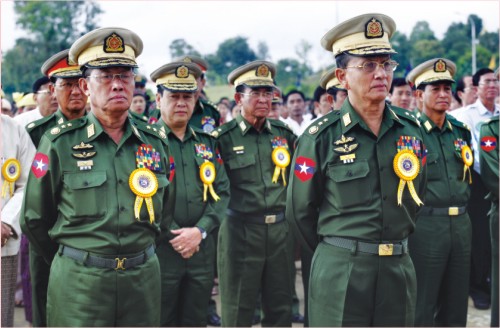

Banker, Trader, Soldier, Spy Sikder Haseeb Khan and Pervez Shams shine a light on the military-industrial complexes in Burma and Pakistan Over the past few decades, a quiet economic transformation has taken place in Burma and Pakistan. In the absence of accountability and transparency, the extent of "security interests" in the economy has increased significantly, compromising the long-term prospects for demo- cracy and economic development.

Barons of Burma As in many other countries, this drove out independent private investors and suppressed growth in key sectors. One telling example of this is rice. In 1868, Burma overtook Bengal to become the world's leading rice exporter. It remained in that position for the next century or so. After the military takeover in 1962, rice exports shrank gradually to almost nil by the late 1980s. In the process, millions of Burmese farmers became impoverished, some were rendered landless, some were forced into unpaid labour, and many ended up fueling various ethnic insurgencies that rage in the country. The second phase started from the late eighties, when SPDC, the current military regime, began to liberalise parts of the economy, in keeping with the trend in the rest of the world to adopt capitalist ways. But a new law, enacted in March 1989, kept the best-growing sectors -- petroleum, natural gas, teak, gems and precious stones, seafood, and minerals -- under the preserve of SPDC. Outside these, many of the state-owned businesses began to be privatised in the style of Russia under Yeltsin, essentially sold dirt-cheap to those with connections to the regime. Since then, two private conglomerates have emerged as the most influential in the economy: Union of Myanmar Economic Holdings (UMEH) and the Myanmar Economic Corporation (MEC). UMEH shareholding is restricted to only the military, active and retired, and their family members. MEC too was set up to advance the "welfare" of the junta. It can conduct business in any sector, and it is authorised to do so outside the regular laws that apply to other private companies. Naturally, the savvy investors in Burma do business by forming joint ventures with one of these companies in order to get access and protection. Patricians of Pakistan The military's influence in Pakistan's economy was expanded gradually, with the creation of hundreds of subsidiaries linked to four foundations: Fauji Foundation and Army Welfare Trust, which are controlled primarily by the army; Shaheen Foundation, controlled by the air force; and Bahria Foundation, controlled by the navy. They are involved in industries ranging from cement to energy, textiles, and food production and trade. These entities and their subsidiaries enjoyed substantial tax breaks, especially during their formative years, which afforded them a window of growth not available to private businesses. They control a sizable amount of national resources, including land. A recent work by Ayesha Siddiqa reveals the extent of this control. The military commands about 12 percent of state land, and is the only government agency with the authority to distribute state land to its members. Those of the rank of major general and above are entitled to 50 acres of land each. The Defense Housing Authority (DHA) controls prime urban land, which is allotted to not just the military but also to key members of the civil service and judiciary as a means to ensure their loyalty. According to Siddiqa's revealing study, the current assets of these enterprises are substantial. The Army Welfare Trust has assets close to $800 million. The Frontier Works Organisation, another military-led enterprise, is the largest construction contractor in the country. The National Logistic Cell, controlled by the army and estimated to be worth $68 million, is the country's largest goods transporter, and maintains one of the largest transport fleets in Asia. Many of these enterprises are managed by retired military personnel and their families. They influence decisions for key strategic posts in public enterprises and government offices related to the economic sectors in which they operate. The political entrenchment of Pakistan's military assures their economic power. At the top of this structure is the National Security Council, a supra-parliamentary body created by Pervez Musharraf, that allows Pakistan's senior generals to play a determining policy role. This role is justified by invoking the global war on terror, and by insisting that Pakistan's civil administration is incompetent and corrupt. The generals have marketed this viewpoint vigorously in Western foreign policy circles since the thick of the Cold War. Buyer, Partner, Supporter, Friend The 2007 Saffron Revolution in Burma made this clear. The West put moral and political pressures on the Burmese junta, but to little avail, for the junta's material ties were elsewhere. China -- Burma's main trading partner and arms supplier, and therefore the only country with leverage over the generals -- expressed "concern," but reaffirmed its policy of "non-interference" in the country's "internal affairs." Known for strategic foresight, the Chinese had expressed their interest in Burma's riches as early as 1985. The article in Beijing Review, "Opening to the Southwest," identified the potential of trade outlets to the Indian Ocean through Burma. These routes have been developed with Chinese investment since then, and the interest in protecting the routes has led China to upgrade Burma's naval bases. China has been the main supplier of raw materials and technical expertise behind Burma's military-led expansion in the public sector, which saw the creation of 480 public enterprises between 1990 and 2002. By 2004, China accounted for 30 percent of Burma's imports, more than any other trading partner of Burma. Between 1990 and 2005, China supplied 74 percent -- $1.7 billion out of the total $2.3 billion -- of Burma's arms imports. Its economic ties to Burma have solidified more now that it has a stake in Burma's oil and gas reserves. Beijing wants "stability" in Burma, not regime change. Pakistan's security economy likewise is dependent on China. China has been the top supplier of arms to Pakistan for the last thirty years, accounting for 40 percent ($6.8 billion) of arms imports between 1975 and 2006, which is double the amount supplied by Pakistan's other strategic ally, the United States. China's share has increased further since the ascent of Musharraf and the start of the war on terror. In recent years Pakistan has become one of the largest recipients of China's foreign aid. By 2006, China emerged as Pakistan's largest source of imports overall, third largest destination of exports, and fourth largest source of foreign direct investment. The biggest sectors of Chinese foreign investment have been strategic in nature, such as joint fighter aircraft and seaport development, the main local partners of which are Pakistan's military elite.

Pakistan and Burma have also maintained warm relations with each other. They became close as generals took over power in both countries, perhaps looking to help establish a circle of autocracy around their common neighbour, India, which, however volatile, remained a multi-party democracy. So when Pakistan was struck with an earthquake in October 2005, Burmese generals were quick to donate syringes and medicine worth $200,000, despite the desperate needs of Burma's own healthcare system. Economic suffocation of democracy In the US, however, a good proportion of this is privately owned, a reaction by private entities to the opportunities spawned by homeland security and the war on terror. Soldiers have stayed soldiers. But in Burma and Pakistan, soldiers and spies are simultaneously bankers, traders, and industrialists, supported regionally by like-minded friends. The garrison economy there has been created through enterprises sponsored by military funds, which go on to out-maneuver other private actors by virtue of their privileged connections. The returns -- or rents, to use the right economic term -- earned through conducting business in this way are further essentially strengthening the position of security interests for the long term. In neither Burma nor Pakistan could such enterprises have flourished in the absence of a commanding role of the military in politics. Command politics breeds crony capitalism. And, as generations of researchers have shown, crony capitalism in turn keeps democracy at bay by preventing the emergence of independent sources of economic and political power that can challenge the regime. Sikder Haseeb Khan and Pervez Shams are freelance contributors to Forum. |