Inside

|

Women Warriors Sharmeen Murshid honours the female freedom fighter I have waited for you for ages, for an eternity and a day. I could hardly contain my excitement when I first discovered, far away from Dhaka, in a little village in Sharupkathi, that a group of young girls had taken up arms to protect themselves and their village from the enemy during the war of liberation. Long before the Mukti Bahini entered the village, or even before Sector 9 was formed, Bastokathi had already built an organised resistance, led by Bithika and her brother Shamiron. It all began a year before that. There was much talk of recognising women's contribution to the war of liberation, and Nari Samaj came to be, and they honoured many women with the title of "Freedom Fighter." Even a petty freedom fighter like myself, who, in a team, would go around in camps singing songs of freedom during the war, was bestowed with that honour. I was restless as I returned home. Humayun, the man in my life, who had himself fought in Sector 9 under Sub-Sector Commander Captain Beg, seeing the crest in my hands, said: "If you truly want to see a woman freedom fighter, then go and find Bithika Biswas." At that very moment I knew why I was so restless. Indeed, singing can inspire, but cannot bring independence. That day I promised myself that I would not rest till I found my warrior sisters -- even if it was a single person. Thus, began my search. And after more than a year, hundreds of interviews, walking over twenty miles on foot, and covering several villages in Kuriana and Sharupkathi, I discovered a whole treasure of untold history. I discovered my warrior sisters. I found my story. Bithika Biswas was a member of Captain Beg's troops. I met her comrades Tofazzal Huq, Porimol Ghosh, and Bulu in Barisal. I interviewed Deputy Attorney General Altaf Hossain, (communication officer of Sector 9) and Obaidur Rahman Mustafa (sector staff officer) and listened to their story in dismay, wondering why it took us so long to discover this. After 27 years, I brought Captain Beg and Bithika together, and together we went back to Sharupkathi where the story began -- the village where Bithika first planned her operation, where she met with Beg's troops and where they were trained and finally incorporated into the bahini as fellow freedom fighters. People thronged from far and wide to see their Bithika, to salute Captain Beg. There were Shobha, Mrinalini, and Konok, who came in quietly and left quietly. Far away from glittering Dhaka, if you care to listen, you will hear the peyara bagan whispering the heroic tales of the Kuriana women. The day was July 11, 1971. The place -- a village in Shorupkathi on the southwest coast of Bangladesh. It was dark and raining hard, and vision was blurred by the harsh monsoon night. The launches were stationed at the ghat (riverbank) of the Kocha Nadi. The launch in the middle was a gunboat carrying the infamous Pakistani captain Ershad -- who within seven days of his arrival in Pirojpur became a terror in the south for his brutal killing of unarmed civilians, women and children. Two young muktijoddha (freedom fighters) stealthily moved through the Hewly forest towards the Kocha riverbank. Their mission was to blow up the launch carrying the Pakistani occupation forces. Two young girls, both around 19 years of age and of slight build, carrying two revolvers and grenades, dared to undertake this suicide operation when their brothers failed to volunteer. They would have to wade through the water to reach the launch, which was heavily armed. They would have to be within yards of the enemy before they could blow it up. The roving searchlights lit the place ever so often. The hard rain and the hyacinth floating in the water were a blessing. They would have to reach the launch swimming in the dark when the searchlight was turned to the other side, giving them a few seconds of darkness at a time. Like fish in water, these girls from the Land of Rivers swiftly reached the launch in the middle and attacked with grenades. Immediately, in response, hundreds of rounds of bullets were sprayed all over the river. That day the girls survived. And so did captain Ershad. But several of his men did not. After 27 years Bithika told me: "I don't know how we survived that day. It was a miracle." Bithika Biswas, Shishir Kona, Shahana Perveen Shobha were three educated girls, in their late teens, from middle class farmer families -- three among the twenty-five I was able to identify and study -- who took up arms and joined the resistance as combatants along the southwest coast of Barisal. During the nine months of war, Bithika and Shishir Kona jointly carried out several dangerous operations under their sector commander, Major Jalil and Captain Beg. They had to kill razakars (collaborators) with bayonets to save bullets. The day Bithika bayonet charged and killed a razakar she truly gained the respect of her troops. Tofazzal Hossain, second in command, said in his interview: "In our march together we soon forgot Bithika and Shishir were women as they walked the miles with us, carried the heavy weapons, and joined the suicide squads. They were our comrades in arms." According to Captain Beg, Bithika was one of his best "men" -- more daring than his boys. When the sub-sector commander, Captain Beg, called on his troops, seeking volunteers for a suicide squad that would have to blow up a gunboat carrying Pakistani soldiers, Bithika and Shishir were the first to volunteer when the men hesitated. I discovered that, like Bithika and Shishir Kona, there were many other women who had also fought as combatants in the field, fighting to protect their own chastity and the chastity of their nation. History forgot that women bravely fought to defend their country, as did men. They were also Bir Uttam and Bir Sreshtho. They were Shaheeds.

She would wear a borkha (veil), visit homes of the razakars, sit on the peace committees that were believed to be working for the army, be a friend to their wives and collect vital information. These young girls would operate in twos, always carrying cyanide. Orders were -- if caught they were to commit suicide rather than suffer at the hands of the enemy. Shahana Perveen Shobha, also around 19-20 years of age, even went into army camps in the cantonment to obtain vital information. During one such operation she and her group were caught. She was tortured and abused but not killed. According to Captain Beg, these operations were of vital importance and many of their missions were based on information obtained by these girls. The people of Bangladesh revolted and resisted, and there was no village without its contingent of freedom fighters. Thus, began the nine-month struggle for the liberation of Bangladesh, a struggle of an unarmed people against one of the most sophisticated and brutal killing machines of the third world -- the Pakistani army. When the Pakistani army was nearly at her doorstep, Bithika with her brother quickly mobilised her young friends to fight the approaching enemy. As she later said: "We would rather die fighting than die like dogs." The Islamic Army of Pakistan had employed the ancient practice of rape as an instrument of war very liberally in Bangladesh. The stories of humiliation and horror had already reached the people of this remote village, where spontaneous resistance groups consisting substantially of girls came into being. A point worth making here is that some of these women were exposed to leftist politics. War came as a threat to their life, dignity, and values. Survival was the strongest motive. In one case, the whole village, along with freedom fighters, took shelter in a dense guava plantation when the Pak army raided it. A mother whose little infant simply would not stop crying had to drown her baby in order to save the community. Can there ever be a freedom fighter greater than she? What honour have we given her? There is a long history of women taking part in armed struggles against foreign occupation in South Asia. One example that comes to mind is the case of the young woman Pritilata of Chittagong, who fought in the uprising against the British in the thirties and laid down her life in a most heroic manner, a Shaheed. She is a household name. During this war, as in other wars in history, women were right there next to the men fighting at many levels -- as caregivers, nurses, spies, cooks, arms carriers, motivators, and above all as armed combatants. Yet, she represents a paradox. As a warrior she breaks out of the mould, but as soon as the war is over she is either obliged or forced to step back into the traditional mould, anonymity and silence. Bithika, who was praised by all her male comrades for her dedication and bravery, did not find any of them courageous enough to accept the warrior as a wife. The question in the mind of her comrades was whether she would be able to work out the "right" equation with her man in a domestic setting where she would have to be a "subaltern." Shishir Kona today refuses to talk about her experience as a combatant. She chose to sink into anonymity in spite of my many efforts to get her to talk. The family wanted her to forget the past and not to be an "embarrassment" to them. Konok cries a lot these days. Her husband left her and married another woman. Konok was a brave fighter but today she lacks confidence and self-esteem. She wanted to be a normal woman with a normal family life. Not a soldier, not a hero. She did not want the past to interfere with that. Shahana with her amazing story of bravery in war, torture and rape in captivity, whose husband was killed by the Pakistan army, was not prevented by her singularity of achievement and experience from contracting a happy marriage to a very caring man who gave her recognition, sympathy, and protection. But this is atypical. The irony is that, at the end of the day, the woman is subject to the same kind of prejudice whether she is a combatant or an ordinary domesticated woman. My search for the women warriors of the liberation war was not an easy one. Many of these women had left their homes, married and migrated, or had fought in one area and lived in another. In Bangladesh, up until 2000, talk of women's role in the war was mainly limited to then providing care, cooking, giving shelter to freedom fighters, hiding arms, passing information, acting as an auxiliary, and, specially and largely, as victims of war.

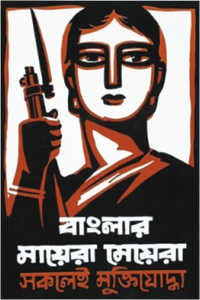

Whatever their history, women have not been perceived as warriors in Bangladesh. The irony is that women have fought against foreign rule alongside men as combatants in the battlefield and outside. For women it was always a matter of breaking the mould. And also, paradoxically, of re-entering the mould they stepped out of. Many were obliged to hide they had fought in the war so as not to ruin their chances of re-entering society, which did not know how to deal with these women. Their stories remained largely untold. No space was created where they could share their experiences. After 30 years only one woman was given state recognition. The 16 volume history of the liberation war published by the government shows an incredible amnesia about the role of women combatants. It only emphasises women as victims. Even their parents were reluctant to take their "dishonoured" daughters and wives back into their families. The traditional view of women thus created a trap, which wouldn't go away nor would she permit it to go away. One would think that by breaking the mould to be a warrior and a freedom fighter, it would create new social equations, but for a woman that does not seem to happen. Despite her courage, her power to make the ultimate sacrifice, she is exactly where she began, behind the curtain, in the mould, struggling to find her place in the home, in the society. Yet, out of this war a new woman is born. Let this generation, and the next, know that in every age, women have fought for justice and freedom. And she must be found, loved and honoured. She is not a Birangana. She is Bir Joddha. She has come of age. Sources used: Sharmeen Murshid is a Sociologist and CEO, Brotee. ARTWORK BY ARIF HAQUE |

Under Sector Commander Major Jalil, a training camp for women was started in Taki. Here, along with Bithika, more than a hundred women trained in armed fighting and espionage. These young girls were trained to spy on and gather information from the army cantonment and the razakars -- local collaborators from religious fundamentalist groups, traitors who opposed the resistance and aided the occupying Pakistani army). Girls as young as fourteen, such as Mrinalini, were part of the espionage team.

Under Sector Commander Major Jalil, a training camp for women was started in Taki. Here, along with Bithika, more than a hundred women trained in armed fighting and espionage. These young girls were trained to spy on and gather information from the army cantonment and the razakars -- local collaborators from religious fundamentalist groups, traitors who opposed the resistance and aided the occupying Pakistani army). Girls as young as fourteen, such as Mrinalini, were part of the espionage team.  There was little information or talk of women as warriors, as combatants and fighters who also had to kill the enemy in order to survive. No badges of honour were given to the women who entered the war silently and left silently. Their ordeals remain largely unanalysed and invisible in the books of history. Some work has been undertaken and much more needs to be done. My own research is an effort to "tell her story" -- a contribution to fill a small area in a vast gap.

There was little information or talk of women as warriors, as combatants and fighters who also had to kill the enemy in order to survive. No badges of honour were given to the women who entered the war silently and left silently. Their ordeals remain largely unanalysed and invisible in the books of history. Some work has been undertaken and much more needs to be done. My own research is an effort to "tell her story" -- a contribution to fill a small area in a vast gap.