Inside

|

Bangladeshis: Moving with the times Rezaul Karim presents a first-hand account of the rise of the upwardly mobile Bangladeshi community in Britain

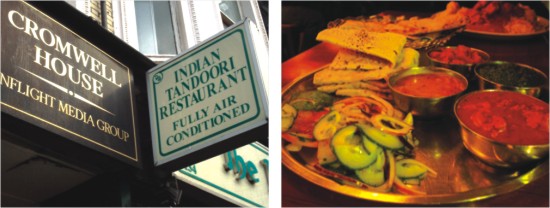

More than one in three Tower Hamlets residents now consider themselves ethnic Bangladeshis, and in the wards of Spitalfields and Bangla Town they make up almost 60% of the local population -- even greater than the proportion of Indians in Southall Broadway. It is a rapidly growing community. In 1991, there were about 37,000 Bangladeshis in Tower Hamlets, and very few anywhere else in London. But by 2001, the population had exceeded 67,000 in Tower Hamlets and there were large new concentrations in West Ham and King's Cross. Currently, the population stands at around 100,000. The Bangladeshis who started arriving in Britain since the 1950s were poorer and often less educated than the Indians who preceded them. The new breed quickly developed one good idea into a national institution: the curry house. The rapidity and thoroughness with which such exotic novelties as mango chutney and rogan josh were absorbed into the British mainstream is perhaps without parallel in any other country. And in the process Brick Lane, near the busy West End, became a food destination for thousands of Londoners. In the last half-century, curry has become more traditionally English than an English breakfast. The "chicken tikka masala" is now a national dish of Britain, and Bangladeshi food is a £4 billion industry in Britain. The vast majority of Indian restaurants in Britain are owned and run by Bangladeshis. Initially, Bangladeshis termed their restaurants as Indian curry houses, but soon they established their own identity behind an industry worth billions of pounds and employing thousands. The hybrid Bangladeshi-Indian curry house is now a household name in Britain. More than 8 out of 10 Indian restaurants in the UK are owned by Bangladeshis, the vast majority of whom -- 95% -- come from Sylhet. In 1946, there were 20 restaurants or small cafes owned by Bangladeshis, in 1960 there were 300, and by 1980, more than 3,000. Now, according to the Curry Club of Great Britain, there are 8,500 Indian restaurants, of which roughly 7,200 are Bangladeshi. However, Bangladeshis in UK claim that there are 11,000 restaurants which are entirely owned by Bangladeshi-Britishers. UK needs skilled chefs Most of the 5 lakh Bangladeshis living in the UK are somehow linked with the restaurant business, and earn about 4.5 billion pounds annually. This is possible because the restaurants made Bangladeshi cuisine very popular across Great Britain, which, to some extent, is changing the food habits of the British people. The celebration of the birthday of British Prime Minister Tony Blair's daughter at a Bangladeshi restaurant also proves the popularity of Bangladeshi cuisine. Moktar Ali, who migrated to UK in the 60s and is now Motwalli of a mosque at Oldham, says that customers usually go to the restaurants where there are good chefs. "Demand for quality chefs in the UK is so high that many of them often switch from one restaurant to another for higher pay," he said. Restaurant traders said that Bangladeshis, despite being unskilled, could learn the skills in one or two years, but work permits are needed for entry into the country. It is also important to train skilled chefs in Bangladesh, they thought. The Bangladesh High Commission is negotiating with the British government in this regard. But the Bangladeshis who, with a population of half a million, are one of the largest ethnic minority migrant communities in Britain, are relatively slower in integrating themselves with mainstream British society and establishing themselves in business, administration, and other well-paid jobs, compared to other ethnic minorities. According to recent research in London, young people from different ethnic minorities are transcending Britain's class system and beating their working-class white peers to well-paid jobs. The new generations of Indian, Chinese, Caribbean and African people are sailing ahead in the employment market, but people from Pakistan and Bangladesh were under-performing compared to other migrant groups. The University of Essex study, which tracked the employment of 140,000 people in England and Wales over 30 years from the 1960s, said that people from Indian working-class families are the most successful. It said that 56% from those families took up professional or managerial roles, while only 43% from white, non-immigrant families went into such jobs. But not all ethnic minorities were experiencing success in the employment market. It said that the fact that a disproportionate number of "upwardly mobile" youngsters were the children of immigrants was to be applauded, but their welcome progress is no cause for complacency, especially when it appears to be so much harder for young people from Pakistani or Bangladeshi families to get ahead. On the other hand, average earning for Pakistani and Bangladeshi men is £150 per week, which is less than that of white men as well as other ethnic minorities, and unemployment is almost three times greater. The figures for women are equally discouraging. Just 11% of Pakistani women are in full-time employment, far higher than the 4% of Bangladeshi women who work. Encouragingly, the figure among Muslim women from an Indian background is far higher at 24%, implying that ethnic barriers may be more profound than religious ones. The Bangladeshi-British experience high levels of social isolation, and are reluctant to promote interaction with other communities for long.

If looked at broadly, the Indian profile appears as white-collar, suburbanized, semi-detached and owner-occupier, the Pakistani profile as blue-collar, inner-city and owner-occupier in terraced housing, and the Bangladeshi profile is blue-collar and council-housed in inner-city terraces and flats. In Britain, no ethnic minority occupies anything like this under-caste position. The Bangladeshis come closest. They are mostly very poor, and they live in tight-knit neighbourhoods, such as Spitalfields in East London. But they are very few in number, and some, at least, of their exclusion appears to be self-chosen. The first, and even the second, generation of the community is still stuck with Bangladeshi politics rather than mainstream British politics, as many pro-independence personalities settled in UK during the 60s as well as through political asylum in the mid- seventies. As a result of this, as well as due to lack of highly-qualified personalities or a lack of their interest in British politics, they did not find time to find their place in British politics and parliament, unlike the British-Indian and British-Pakistani community.

Though the economic backbone of the Bangladeshi community is still restaurant or catering business, some of the Bangladeshi-British have gone up to the extent of being nationally honoured in Britain. Currently, the second and third generations are graduating and going into white-collar jobs, and are also taking interest in asserting their position in British administration, politics and business institutions. Though their numbers are still very limited, the trend is upward and encouraging. In 2006, a large number of Bangladeshi students achieved tremendous success in O level and A level examinations and most of them were admitted into renowned universities in UK. Bangladeshis coming out from curry business Let's take the example of young Barrister Akhlaq Chowdhury, son of Azizur Rahman, who migrated to London in 1961 from Karimganj in Sylhet. Sitting in his chamber in London, Chowdhury said that it was very easy for the British-Bangladeshis to enter the restaurant business, but they are now slowly coming out of the cycle and becoming experts on engineering, medicine, law and many more higher professions. He confessed that there are obstacles from within the community, and that the Bangladeshi community gives no direction to the younger generation to go for higher education They are also holding the posts of economists. One of them, Citigroup's macro-strategy managing director, Iftekharul Islam, thinks that Bangladesh should develop its knowledge in information technology to adjust with the pace in the age of globalization. Renowned software company Mathworks managing director, Sham Ahmed, said that he was now ready to help Bangladesh in expertise development. "I want to contribute to the welfare of Bangladesh as successful diplomat Anwar Choudhury is doing for Bangladesh," he said. Asif Ahmed, director, Asia International Group of UK Trade and Investment, said that the number of Bangladeshis in government services is increasing, and that there were some areas where the number of Bangladeshis was higher than other ethnic minority communities in UK. There is good representation of Bangladeshis in local government level. A Bangladesh-born Baroness, Pola Manzila Uddin, is one of the prominent individuals who has made it to the top. Member of the House of Lords of Britain, Pola Manzila Uddin severely criticizes dragging politics of Bangladesh to Britain. "Involving in BNP-Awami League politics in a foreign land is dangerous," she said, and suggested that more British-Bangladeshis should join the mainstream political parties in Britain. Pola Manzila said that the Labour Party, which is now in power, should nominate British-Bangladeshis in the constituencies of the Bangladeshi-dominated East London. "Bangladeshis also should forget all divisions and vote for the British-Bangladeshis for their victory." Lutfur Ali, one of the top executives of a management company in the UK, however regretted that some of the third and fourth generation British-Bangladeshis are getting involved in crime as a consequence of drug addiction. "The number of addicts is not that high, but there are many reasons for us to be anxious about them," he said. Lutfur Ali, whose father migrated to the UK in 1935 from Balaganj of Sylhet, said he is now trying to get nomination from the Labour Party. The British-Bangladeshis said that the children of the third generation are now more educated and getting into better and mainstream jobs and engaging themselves in the policy-making institutions. The economic base of the British-Bangladeshis, however, is still restaurant business. Most of the 5 lakh British-Bangladeshis are involved in it, and are earning Tk 52,000 crore every year.

Learning English New guidance about signing on from April could force those with poor language skills -- a problem which affects about 40,000 claimants, according to the government -- to take lessons. The move is part of a range of measures aimed at tackling unemployment and poverty levels among ethnic minorities. Jim Murphy, the welfare minister, said it was unacceptable that unemployment rates and earning rates among British ethnic minorities were worse than those for white claimants, while half of children from Pakistani and Bangladeshi families in the UK live in poverty. According to the UK Foreign Ministry officials, the government wants greater take up among the unemployed of a £14m training scheme for those on the dole to help with language skills. The £4.5m currently spent on in-house translators within job centres could be better spent on educating individuals to speak better English. Rezaul Karim is Chief Reporter and Diplomatic Correspondent of The Daily Star. |

N

N

Nowadays in Britain, the new generations of migrant families are beginning to take control of their own destinies. As Britain's once-migrant families move on into the second, third and, soon, fourth generation, it becomes more and more clear that they are not just at the receiving end. Through their own actions -- drawing on their own social networks, economic enterprise and family backgrounds -- they have taken charge of their lives.

Nowadays in Britain, the new generations of migrant families are beginning to take control of their own destinies. As Britain's once-migrant families move on into the second, third and, soon, fourth generation, it becomes more and more clear that they are not just at the receiving end. Through their own actions -- drawing on their own social networks, economic enterprise and family backgrounds -- they have taken charge of their lives. Bangladesh High Commission counselor in London, Saida Muna Tasneem, said the high commission keeps on hunting for them: "We have developed some network of young enterprising British-Bangladeshi third generation because they are probably our best asset to invest in and attract them to visit Bangladesh and engage them to promote Bangladesh's image."

Bangladesh High Commission counselor in London, Saida Muna Tasneem, said the high commission keeps on hunting for them: "We have developed some network of young enterprising British-Bangladeshi third generation because they are probably our best asset to invest in and attract them to visit Bangladesh and engage them to promote Bangladesh's image."