Science Feature

Fossil unveils new reality

A new discovery revealed that early female hominids were much smaller than males. A team of Kenyan scientists was come to this decision after finding an ancient skull and jawbone from two early branches of the human family tree Homo erectus and Homo habilis. The scientists think both Homo erectus and Homo habilis must have evolved from a common ancestor 2-3 million years ago. A new discovery revealed that early female hominids were much smaller than males. A team of Kenyan scientists was come to this decision after finding an ancient skull and jawbone from two early branches of the human family tree Homo erectus and Homo habilis. The scientists think both Homo erectus and Homo habilis must have evolved from a common ancestor 2-3 million years ago.

The skull was the first discovery of a female Homo erectus. It suggests mankind's upright ancestors may have been physiologically closer to modern gorillas and chimpanzees, which also exhibit big differences in size between males and females, than had been supposed.

Dr Emma Mbua, one of the team members said, "Prior to the discovery of the new specimens, scientists did not know that Homo erectus males were far larger than the females".

These new evidence find in east Africa's Rift Valley may invalidate the idea that human prototypes evolved one after the other in a linear fashion from Homo habilis to Homo erectus, ending with modern humans.

Both fossils were found in 2000 east of Lake Turkana. But the Homo erectus skull, dating back 1.55 million years, was slightly older than the Homo habilis jawbone, which was found to be 1.44 million years old, the scientists said.

The basic evolutionary story -- that all humans came "out of Africa" after evolving from apes in the Rift Valley around 5 million years ago -- remains unchanged and may even be strengthened, the scientists said.

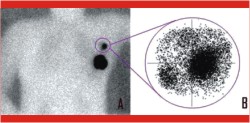

New device to probe breast cancer  A team of French scientists has developed a miniature hand-held imaging device called a Peri-Operative Compact Imager (POCI) that allows surgeons to precisely identify breast cancer. A team of French scientists has developed a miniature hand-held imaging device called a Peri-Operative Compact Imager (POCI) that allows surgeons to precisely identify breast cancer.

The camera has been approved by France's healthcare products safety agency (resemble FDA in the US) and already tested on 110 patients with breast cancer. According to Tenon Hospital and Paris Public Hospitals, the performance of this cutting edge technology is very encouraging.

The camera detects gamma rays emitted by tumors that have been labeled using a radioisotope. This is done by injecting a radioactive solution into the breast tissue and is already standard practice.

The signals picked up are then amplified and transferred to a computer to be digitized, allowing the position and energy of each gamma signal to be observed in real time on a screen. Once the tumors have been removed, the surgeon can use the camera to scan the area again to make sure there are no traces of residual radioactivity.

The POCI, which is just 9 centimeters long, is less cumbersome than the gamma cameras currently used in medical examinations. It can resolve areas as small as just 2 millimeters across, compared with 7 millimeters with standard cameras.

The researchers say this means it could help save lives by identifying "sentinel lymph nodes" that currently go undetected. A sentinel lymph node is the lymph node into which fluid from the area surrounding a tumor drains.

The camera can also differentiate between two tiny tumours lying close together. And weighing just 1.2 kilograms, an articulated arm is not needed to operate it - unlike existing cameras.

|