sharat

(autumn) hemanta (late autumn)

THE

early autumn season of Shorot comes in Bhadro

and Ashwin. Shorot is characterised by clearing

skies at the end of the Monsoons above,

and below is the pungent odour emitted from

golden jute collected and processed by farmers

on every piece of available dry land. Then

Hemonto swings through the fields of Bengal

with cooler days in the months of Kartik

and Ograhayon. Farmers take to clearing

harvested fields to make way for winter

crops and the iconic bucolic beauty of Bengal

takes shape in both these seasons where

the landscape is laced with Shaplas and

Kashphools in full bloom.

THE

early autumn season of Shorot comes in Bhadro

and Ashwin. Shorot is characterised by clearing

skies at the end of the Monsoons above,

and below is the pungent odour emitted from

golden jute collected and processed by farmers

on every piece of available dry land. Then

Hemonto swings through the fields of Bengal

with cooler days in the months of Kartik

and Ograhayon. Farmers take to clearing

harvested fields to make way for winter

crops and the iconic bucolic beauty of Bengal

takes shape in both these seasons where

the landscape is laced with Shaplas and

Kashphools in full bloom.

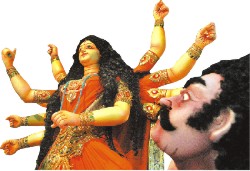

DURGA

Puja, its universal appeal

The most celebrated religious festival among

the Bangalee Hindu community is Durga Puja.

During the days of Durga puja colourful

idols turn parts of the country into a glittering

landscape, sounds of dhak and dhol, revv

up the mood of jubilation.

Durga

puja has a history that dates back in the

ancient period. There is much debate regarding

the origin of Durga Puja. It's history as

well is quite complex. For example in Kritivasa's

Ramayana, Rama does the Akal bodhon

in autumn (Sharat) to do the Durga Puja.

On the other hand king Surath used to perform

the puja in spring. This puja is now known

as Vasanti Puja.

Durga

puja has a history that dates back in the

ancient period. There is much debate regarding

the origin of Durga Puja. It's history as

well is quite complex. For example in Kritivasa's

Ramayana, Rama does the Akal bodhon

in autumn (Sharat) to do the Durga Puja.

On the other hand king Surath used to perform

the puja in spring. This puja is now known

as Vasanti Puja.

According

to the famous scholar Amulyacharan Vidyabhushan

the name Durga appeared from Dakshakanyan

(daughter of Daksha). In the ancient times

the statue of Dakshakanyan was

the symbol of fire. The statue of Dakshakanyan

was yellow at that time and was set on the

Kunda. Later the ten sides of the

Kunda (hollow in the earth) became

the ten hands of Durga. During the last

part of the Vedic age, Dakshakanyan

evolved in to Uma, Uma in to Ambika and

Ambika in to Durga.

Durga

Puja may have been held in the ancient days

but its character and nature were different

then. The Durga Puja that is prevalent today

in Bangladesh is a folk form of the ancient

custom. At present it is being celebrated

in autumn.

Usually

Akal Bodhon of Durga takes place on the

sixth lunar day of the full moon in the

month Aswin. The seventh, eighth and the

ninth lunar days are the days of Durga puja.

The immersion takes place on the tenth lunar

day, which is called Vijoya Dashami.

From the next day of immersion starts the

custom of extended Vijoya greetings. Durga's

elder daughter Lakshmi is worshipped on

the full moon in Aswin. In the month of

Kartik on the day of Sankranti (the passage

of the sun from one astrological sign to

another) Durga's son Kartik is worshipped.

Saraswati, Durga's younger daughter is worshipped

in the month of Magh on the fifth lunar

day of the full moon. There is no puja for

Ganesh as he is always worshiped along with

other gods.

Durga

puja was first transformed into a grand

festival in Calcutta not only for celebration.

It also served the purpose of entertainment

for the English masters. Description of

the Durga puja can be found in contemporary

journals and novels. Probably from the nineteenth

century the faint echo of the puja in Calcutta

spread in to Bangladesh. The landlords and

the elites used to reside in Calcutta at

that time. They introduced the entertainment

and amusement of Calcutta in to the lives

of their peasants. The zamindars played

the most important role in transforming

Durga puja in to a universal festival in

this region. For some it was a time to exhibit

wealth and for some other people it was

the time to show kindness and generosity.

In

1946, after the communal riots in Bangladesh

especially in Noakhali many families left

the villages to come to the city. In the

making of the deity Durga, people from different

castes perform different duties. As some

of the caste became displaced from their

birthplace, it became quite difficult to

organise the puja. In this backdrop in the

year 1946, Brahmins and non-Brahmins jointly

came to the villages ignoring their caste

differences to collect donation and organise

the puja, which is now known as Sarbojonin

Puja.

Since

the beginning of the Pakistan regime most

of the pujas organised here in Bangladesh

were Sarbojonin. Apart from these,

pujas were organised by individual elite

families.

After

the independence of Bangladesh the Dhakeswari

temple of Dhaka has been transformed in

to a site for the celebration of the Durga

Puja. Most of the mandirs of Dhaka are situated

at the old part. Almost all the idols of

Dhaka are immersed in the river Buriganga.

Huge rally takes place, with thousands of

people dancing all the way to Buriganga

with the beat of drums (dhak and dhol).

Due to the congested status of Dhaka, it

is quite difficult to turn the festival

in to a grand one. The most spectacular

mondops are built outside Dhaka. Chittagong

and Narayanganj has huge puja festivity.

Traditional Durga puja mela (fair) takes

place around different mondops. This fair

attracts people of all ages. Statues of

clay, sweet treats like khaja, goja, batasha,

kodma is sold in the fair. Children are

most likely to gather around these stalls.

Devotees of all age visit the goddess and

pay their respect. Like all the other religious

festivals, the theme of Durga puja is nurturing

the essence of ecstasy.

In search of festivals

Abul

Momen

How does one become festive?

Definitely

not by simply putting on festive dresses,

which means spending more on clothes. Also,

it does not end in improved diets. Nice

dresses and good foods are obviously the

two common features of a festival anywhere

in the world. But it is the holiday mood

of course that sets the tune of the mind

making it keen to enjoy. A joyous mind sings

and dances and takes part in all sorts of

hilarity?

Definitely

not by simply putting on festive dresses,

which means spending more on clothes. Also,

it does not end in improved diets. Nice

dresses and good foods are obviously the

two common features of a festival anywhere

in the world. But it is the holiday mood

of course that sets the tune of the mind

making it keen to enjoy. A joyous mind sings

and dances and takes part in all sorts of

hilarity?

But do we have such festivals?

During the two Eids we put

on nice clothes. Some of us compete in spending

on new clothes to win, not in the test of

taste but, in the war of wealth. Some also

spend lot on food. But then? What other

options do we have to express our holiday

and festive moods?

The Bengali Muslims do not

have community songs and dances. A festival

is a community participatory outdoor event.

The jamaat (of Eid namaaz) is an outdoor

and participatory exercise, but truncates

the society by prohibiting women from participating

with the males, and secondly, it is purely

religious prayer, at best could be the 'bismillah'

ceremony of the festival. But then you have

no more outdoor participatory programmes

where the whole society, male and females,

could enjoy themselves in togetherness.

Eids are primarily religious events, and

the festive parts, whatever they have, are

unfortunately for the rich people, who are

more and more getting involved in unhealthy

competition of spending at individual level.

And in a poverty-stricken

society the religious events could take

a festive look only among the haves, who

form only a smaller section of the population.

The bulk remain unfed, unclad, not to speak

of good food and new clothes. And again,

as we have a sizeable number of religious

and ethnic minorities in our country any

religious programme becomes sectarian in

this country.

So Eids, for various reasons,

falls short of a national festival. It is

at best a religious festival of the Muslim

community.

Puja is full of festivity.

With songs, dances and art-works and day-long

outdoor celebrations it is a festival. But

as a religious one it is limited only among

the Hindus, who are the largest minority

community in the country.

The Bangalees as a traditional

agrarian community are deeply attached to

nature, which is abundant here on a very

fertile ground, and is very colourful and

lively too. The rural folks not only depend

on the bounty of nature but perhaps this

long active association with nature kept

alive in their mind the pagan passions for

nature and natural elements. People believe

in nature's supernatural powers, see behind

nature's every act of fatal consequences

the hands of god thus nurturing in them

a mind too vulnerable to all sorts of passionate

callings in devotional lines which normally

generate from the mysteries or forces or

wonders of nature. Occult and obscure practices

are ripe in this condition among the common

rural people.

The devotional people revere

their mystic leaders and centring him finally

organise, apart from the regular congregations,

at least one event a year drawing people

from far and near. These occasions often

grow into big events taking almost the shape

of a festival with a fairly good part of

a fair in it. These are however all local

festivitis. Like the Muslims both Hindus

and the Buddhists also have such occasions

where at the local level they overlook the

religious demarcations.

In this sense Bangladesh

could be termed a land of fairs and festivals.

But where are the festivals

that people all over the country celebrate

together.

We have, like any other

country, some national days, such as-Shaheed

Dibash or the Martyrs Day, Swadhinata Dibash

or Independence Day, Bijoy Dibash or Victory

Day.

In some countries Independence

Day is observed with great pomp like a festival.

But in our case the formal state fuuctions

are the day's main events. After all festivals

are not state functions, but totally social

events. In fact, festivals are successful

only through people's spontaneous participation.

In a very unique development,

one of the most tragic incidents of our

history finally took the shape of a festive

occasion for the nation. Just as some of

our local fairs gradually crossed the barriers

of their religious roots through people's

spontaneous participation so is the case

here. What was originally an occasion of

mourning, became, in course of time, an

occasion of remembrance, and then from remembrance

to paying respect, eventually covering all

the aspects of Bengali art and culture took

the shape of a real national festival. Ekushe,

the Mother Language Day, has its symbols

in the monument, and as it has been replicated

throughout the country, specially in all

the educational institutions, gradually

the educated Bangalees have developed deep

involvement with the spirit and culture

of Ekushe. And when a nation overcomes the

ups and downs of history, especially when

makes progress through continuous struggles,

it would definitely not confine the symbolic

occasion only in mourning and sorrow. The

emotion of mourning then really turns into

the power of determination. The nation that

transforms bereavement into bravery will

not express sorrow but project will-force

in celebrating the day. All through the

sixties we have seen Ekushe embodying all

the creative and intellectual fervour of

a rising nation. Innumerable songs were

tuned, poems composed, essays written, so

many programmes held, so many people participated

in all those activities that the occasion

became one of national rejuvination.

Originally the issue in

this case was language, to be specific,

recognition of mother tongue Bangla as the

state language of the country, and the day

was of mourning as several demonstrators

were killed by police firing, and it is

called the martyrs day. It is natural for

the day to gain some politial significence,

which it gained. But finally it became an

occasaion of searching our roots and waking

up ourselves as a nation. It did not remain

confined either to language or martyrs rather

through literary publications, arts and

cultural expositions, meetings and through

discussions and peoples' spontaneous participation

in every activity it became a festive occasion

for us. So much of emotional outbursts,

so much of creative exuberance and participation

of so many people just made Shaheed Minar-based

morning schedules as inadequate and not

befitting for the occasion. People spontaneously

organised fairs, chalked out day long to

month-long programmes. Ekushe February today

is our national festival - a secular cultural

festival.

Some leading Bengali intellectuals

have always felt the necessity of a secular

festival for nation-wide celebration, and

they selected Bangla 'Nababarsha' for the

event. Traditionally the Hindus and the

Buddhists in general and the trading community

irrespective of religion and faith particularly

used to celebrate the Bengali New Year.

During the time of the rise of Bengali nation

we needed to exploit every potential issues

and occasions to accelerate the pace of

our forging into a nation and our rise as

a unit of Bangalees. Like popularising Bengali

at every stage of life, like acquainting

people with Bengali literature and culture

the celebration of Bengali New Year also

became an important trend-setter event for

the rising nation. Chhayanaut, the popular

cultural group of Dhaka, introduced an outdoor

morning musical programme at the Ramna Park

to invite and receive the new year. The

significance of new year, the scope to come

closer to nature, special environment of

morning musical programme, novelty and speciality

in dress and food, the mood of holiday together

gave it the colour and quality of festivity.

Such musical celebrations

of Pahela Baishakh are still mainly urban

events. In the rural areas some such initiatives

are taking shape, and some traditional fairs

are also being rejuvinated being inspired

by the urban initiatives .

The third national festival,

I believe, could be the Victory day. Victory

in a liberation war is by far the biggest

occasion for any nation, and where it comes

at the expense of three million lives, exodus

of crores of people, two hundred thousand

women being raped, and above all, if it

comes through transformation of a seemingly

idle, home-sick nation into a brave warrior,

than the occasion is a great one in all

its significance. Moreover, the time is

beautiful for holding a festival. December

is dry and cool, traditionally our season

of festivity. With the annual examinations

over, young and old alike are ready to have

festivities at that time of the year. With

the popularity of Bijoymela we can see that

already the nation is participating in a

festival of national scale. Only the political

divisions among the people, and with anti-liberation

forces becoming powerful in the society,

there are still some misunderstanding and

unwanted debates in the society which make

it hesitant and confused about celebrating

the victory day in the same spirit and joyous

mood.

However, we know history

will march forward, the nation will go ahead,

and all the confusions and hesitations will

wither away. The nation will one day find

its rhythm back and will celebrate at least

three festivals a year as a nation. In fact

it already is celebrating those. Yes, unfortunately

not always as a nation at the moment.

.........................................................

The author is the Resident Editor at Chittagong

of Bangla daily, Prothom Alo.