|

||||||||||||

Martyred Intellectuals' Day There are but a few days in our history more painful and engaging of the collective psyche of a nation than 14 December. On this day, we remember and we grieve. We remember with a heavy heart the loss of the brightest stars of our intellectual firmament and we grieve for the fact that we will hardly be able to produce the likes of those that we lost. We feel their absence deeply and will continue to feel so for as long as we survive as a nation. The killings were a well planned strategy to divest a nation that has just emerged as an independent country of its thinkers, professionals and teachers to cripple its progress. This year, as in the past, we have put together a collage of pictures and articles, mostly reminiscences and personal, insightful thoughts about some of the luminaries by some of those who had been intimately associated with them. This year's Martyred Intellectuals' Day Supplement, like in the past, is both a reminder and resolve. It is a reminder of the trauma that the nation had to undergo, and a resolve not to let the perpetrators of the heinous crime go unpunished. --Editor Intellectuals: The Martyred and the Living Serajul Islam Choudhury Our martyred intellectuals belong to the people of East Bengal, who had discarded the two-nation theory of nationalism. The rejection was not merely theoretical; its practical significance was disastrous for the Pakistani ruling class whose intention was to turn East Bengal into their colony. To say not to Pakistani nationalism and turn to Bengali nationalism, which is what the martyred intellectuals had done, meant removing the very raison d'etre of the Pakistani state, asking the people to rise in rebellion against national oppression. And that is precisely what the Bengalis eventually did in 1971. The process started with language discontent and movement which began right at the inception of Pakistan as a state. Initially it was an intellectual movement, but soon it took on a political character. The intellectuals had protested against the state's presumptuous move to impose Urdu as the state language on the Bengalis; and the entire population of East Bengal lent their support to that protest. The toiling masses had their own disappointments, and they found in the new movement an outlet for their grievances. Step by step the movement grew and was strengthened by popular discontent. The design of the rulers to keep East Bengal as a rich field of exploitation became clearer with the passage of time and the demand for autonomy continued to gain momentum. The majority of the Pakistani population lived in East Bengal, and to deprive them of their rightful share of state power a curious, and totally undemocratic, system of parity was devised. The intellectuals and political leaders demanded universal adult suffrage, which the rulers had to concede, finally clearing, without their knowing it, the way for the breaking-up of the unnatural state that Pakistan was. The contradiction between the state and the intellectuals was beyond resolution. Needless to say, all our intellectuals did not promote Bengali nationalism; there were some who clung to the establishment and acted in a manner which was reactionary. The intellectuals come from the middle class, which class is well-known for its wavering on ideological issues. But those who saw the national question from the historical and objective point of view were on the side of Bengali nationalism and felt the irresistible urge to take up a position which the state found intolerable. The intellectual, we know, is a person who interprets the world and engages himself/herself in the dissemination of the interpretation to the people. This is what the intellectuals who had rejected Pakistani nationalism had done, earning undisguised state hostility. The martyred intellectuals have played their role; they have influenced the movement of history and become a part of it. But the important question is what the living intellectuals have been doing since independence. To be precise, the intellectuals have not explained what went wrong with the state and society in Bangladesh, not to speak of taking that explanation to the public. In fact most of them have affiliated themselves in varying degrees to the ruling class, a class that comprises contending parties, but is in reality a conglomerate of selfish interests. The leadership of the major political parties makes use of the public but remain far removed from them. To put it in unmistakable terms, what ails Bangladesh -- economically as well as ideologically -- is capitalism. Capitalism had had its virtues, most of which it has lost in the process of its development. Capitalism in Bangladesh today is without enterprise and entrepreneurship; it relies on the gaining of riches through plunder and clings to the world capitalist system, even if marginally. It is certainly not without significance that the capitalist world was prepared to support our agenda of autonomy but not that of independence, fearing that the independence, movement would be led by extremists. By extremists they meant the leftists. India herself was interested in a quick ending of the Bengalis' war against the Pakistanis not only because of the heavy pressure of refugees but also in the apprehension that a protracted war might result in a leftist take-over of leadership. And the way the capitalist world which opposed the liberation war has established its control over Bangladesh is a proof, if any be needed, of the surrender of our rulers to capitalism. The emancipation that has been the dream of the people depended on a social revolution; but the class that took over state power did not believe in that kind of a revolution. For them the gaining of power was nothing short of a revolution and, in the interest of their security and continuity, they had pledged to themselves to keep the state and society as it was before. The original constitution of Bangladesh had socialism as one of the regulating state principles. That, however, was more of a compromise than a pledge. The Awami League was not known for its faith in socialism; it was only in the 1970 Election Manifesto that the party promised to establish socialism, in view of the popular expectation. Not to speak of a particular party, Bengali nationalism itself has been perceived by the bourgeois leadership in control of the nationalist movement as compounded of two elements -- one explicit, the other implicit. Explicitly its leadership believed in linguistic nationalism, but implicitly it had nurtured its trust in capitalism. This became clear when the leadership took over state power. The rulers displayed their acceptance, in some form or other, of the idea of nationalism, but remained believers in capitalism. In other words, despite their rejection of the two-nation theory, they continued to be capitalist in ideology and outlook. We have been experiencing the outcome of this clinging to capitalism. Socialism has been successfully driven out from the list of state principles; even secularism has not returned, having been thrown overboard for reasons of political expediency. Since 1972 inequality, which is direct result of the capitalist dispensation, has been continually rising, forcing patriotism to decline. The collective dream of a truly democratic state and society has been shattered by the phenomenal rise of the greed for personal aggrandizement. In almost all spheres of life, the national interest has been made subservient to personal interest. Privatization continues to threaten public property, including rivers and wetland. Education and healthcare have become commodities. National wealth is being cheerfully handed over to foreigners. Human rights-violation and extra-judicial killing have reached a magnitude never known before. Ecologically the country is facing many dire threats. The fair name that Bangladesh had owned through the liberation war has been darkened by corruption and nepotism. In the comity of nations Bangladesh is being perceived as a country of natural disaster and political mismanagement. Within the country there is despair prevailing everywhere. Behind all these it is capitalism of a peculiar kind that is operative. The intellectuals are not silent. One hears their voices in talk shows, round tables, occasional gatherings, press conferences; they sign statements and write in newspapers. More often than not, they speak about the symptoms, ignoring the disease. They demand reforms and corrections, and are oblivious of the fact that what we need is a social revolution that has been pre-empted by the ruling class. What is worse, many of our intellectuals are tied to the apron strings of the two major political parties and their views conform to the party line. In a word, their role remains very different from that of the martyred intellectuals, and their isolation from the people makes them ineffective. The root cause is their acceptance of the capitalist ideology. In this crucial respect there is no divergence between them and the ruling class. Not unlike the political leaders of the ruling class, they too support capitalism, although they would not confess to it publicly. This ideological weakness holds them back and does not allow them to participate in the people's movement for emancipation in the manner the martyred intellectuals did. In the inevitable contradiction between the state and the public, the living intellectuals serve the state and not the public. Political independence is a significant achievement, because among other gains it has resolved the national question and allowed the class question to come to the fore. And it is the class question that has to be addressed now by those who believe in the emancipation of the entire people, including that of their own. The martyred intellectuals have left a legacy that they would expect us to carry forward. Those who are living can be vitally alive, effective and worthy of being called intellectuals if they join the people in the way their noble predecessors have done. For this it is imperative that they disaffiliate themselves from their capitalist moorings. This is the primary task, others would follow. Who carries their torch? Rashid Askari The killing of the Bengali intellectuals during 1971 is, in some sense, far more premeditated than the notorious Holocaust. Although the Holocaust claimed twice as many lives compared to our Liberation war, the murderous Nazi did not pick and kill hundreds of top-notch intellectuals in such a short time span as did the bloodthirsty Pakistan occupation army and their local collaborators the Razakar, Al-Badr and Al-Shams. Why did they murder the best brains in the country? Although a few could escape by pure chance, the mission was the elimination of all the intellectuals from Bangladesh with a view to cripple the country with ignorance and eternal backwardness. The assassinated intellectuals were the highly educated academics, writers, physicians, engineers, lawyers, journalists, and other eminent personalities of the country who helped liberate the nation from prolonged Pakistani subjugation. The martyred intellectuals were a very great wealth of talents. The French Enlightenment figures, Voltaire, Rousseau, Montesquieu, and John Locke kindled popular interest in the three basic principles of French Revolution Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity. Similarly, our intellectuals ignited masses of people in the spirit of freedom which resulted in gaining independence through a liberation war. They were the voice of conscience in all the scenes of the independence struggle. They were no less than Socrates, killed by vested interests for showing his people the right way or Galileo, condemned to life imprisonment for his so-called heretical beliefs or Bruno, burnt alive at the stake for telling the truth. Our intellectuals, too, were butchered by the neo-colonial forces for showing us the road to liberation and inspiring us to fight for our freedom of thought and expression. They were fully successful in instilling their own thoughts and ideas in the people who had been blinded to the real needs of their country for ages. But what kind of legacies do our present-day intellectuals carry from our history? It is hard to believe that they are left with any legacy from the martyred intellectuals who had laid down their lives for their country. On the contrary, most of today's intellectuals have chosen a different path. They may fall roughly into three groups. The first group consists of the self-centred intellectuals who are only concerned with their own wants and needs, and never think about other people's good. They are mostly varsity academics and work part-time with different private institutions, NGOs, multinational companies, and projects to earn a fortune. Most of their time is spent juggling between their workplaces, and no spare time is left to think about their country and its people. The second-group of intellectuals are highly politicised. They are the intellectual vanguards of their party, and see everything around them with a partisan eye. They are social climbers, and their sole aim is personal aggrandizement. They wait their turn in order to grab the chance of holding high office. They suck up to people in authority for achieving goals. They toe the party line so strongly that they often give highly lopsided views on even undisputed facts and common public interests ignoring objective truth. The events of our art, culture, literature and history are also split by these one-eyed intellectuals. Years of polarisation have sapped them of their integrity and moral standards. The third group comprises of the seeming nonpartisan intellectuals who love being called 'civil society'. Most of them are the hired hands of international hierarchies working in their native country. It is a part of their job to pick holes in political affairs. They give voice to different national crises in such a grave manner as if the country has completely gone to the dogs, and there is no escape from it. The implication written all over their faces is that the nation would have its best governance only at the hands of these civil society guys. Although they put on an air of neutrality, they must be working willy-nilly to realise Colonial mandate. One may reasonably smell a hidden agenda behind their activities. These three groups of intellectuals have nothing common in them other then ignoring true love for the country. Be that as it may, one must ask what the responsibilities of today's intellectuals are. Noam Chomsky has said, "It is the responsibility of intellectuals to speak the truth and to expose lies." Antonio Gramsci, a theorist on intellectual exercise argued: "Intellectuals view themselves as autonomous from the ruling class." Jean Paul Sartre considered intellectuals as the moral conscience of their age, and the observer of the political and social situation of the moment, and urged them to speak out freely in accordance with their consciences. Do our intellectuals speak the truth and expose lies? Are they able to do things and make decisions of their own accord? Do they have a voice of conscience? The bulk of our present intellectuals in Bangladesh are far away from these basic tenets of true intellectuals. There are, however, some good intellectuals who, amid the razzmatazz of the fake intellectuals' activities, are working steadily to voice the thoughts and needs of mass people. It is they who cherish the true ideals of the martyred intellectuals from the bottom of their heart. If good triumphs over evil in the end, all the three groups of pseudo-intellectuals must be overshadowed by these few, for they are carrying the torch for the martyred intellectuals. The writer teaches English Literature at Kushtia Islamic University.

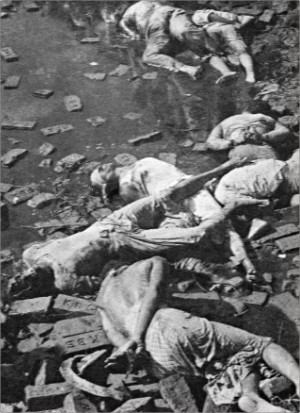

Reflections on a picture Shahid Alam Ever since I first saw that photograph, I have never failed to be moved by it. I am talking about Rashid Talukdar's picture of a head lying amidst a scattered pile of bricks and mortar in what appears to be a pool of brackish water. The picture is vivid, and, while the colours involved cannot be discerned, the black-and-white composition (as is often the case) tells more than it shows and allows the imagination so much room to soar. Talukdar's photo appears surreal, almost like a Salvador Dali painting transformed and adjusted for a still camera shoot, and it brilliantly portrays the day that is being observed this day: Shaheed Buddhijibi Dibosh, or, Martyred Intellectuals Day. It is at once poignant, somber, ghastly, and a mute story of what the intellectuals sacrificed, their today, so that the nation could see the light of freedom and independence tomorrow. At first glance, you could not be faulted if you did not take any notice of the head and thought it to be a somewhat bizarre part of the view. On a closer look, however, the image of the head will more likely than not be forever etched in your head, and will give a fair indication of the way many of the intellectuals died. The face could so easily be mistaken for a mask, pale, expressionless, detached from a body, hollowed-out eye sockets. There! The blank eye sockets and head minus body! That is how that poor man was horribly tortured, and, eventually, killed. The eyes were gouged out, almost certainly when he was alive, and his head severed from his body, probably after he was killed. All the intellectuals who were prematurely removed from the land of the living, thereby abruptly depriving all those that they had been enlightening, were thus murdered. No, not in exactly the same fashion; some in a hail of bullets in the heat of frenzied assault by the Pakistan army, others cold-bloodedly, selectively, by right-wing Bengali religious fundamentalist-extremists who tortured their victims in a gamut of horrific ways before dispatching them, also by a variety of means. They were university teachers, journalists, writers, doctors, engineers, and artists. They were not killed in one fell swoop. The army had engaged in methodical killing of several in the initial stages of the liberation war, and, as it was winding down to its denouement of the birth of Bangladesh as a sovereign, independent nation-state, the army and its local henchmen, in a planned ritual, disposed of the rest. They had committed what someone has called “cerebrogenocide” on the Bengali nation. The intellectuals, because of their higher enlightenment, are regarded as guides of a nation's ethos. Furthermore, they are seen as the custodians of a nation's history and culture. That is why, when they become a part of history by having their lives cut short violently for being ethical guides and custodians of culture and history, that is tantamount to carving out a piece of a nation's soul. I knew some of them, heard of a few, while the rest, probably because they had not attained nation-wide fame, I had not heard of. That is poignant. They were not allowed to realize their full potential. Maybe not all, or any, would have succeeded in going beyond respectable obscurity, but, we will never know now, will we? We will never know the putative impact for the good they could have had on the fledgling nation-state. My father was a student in the History department of Dhaka University in the late 1930s. That consideration, plus my own keen interest in the subject, directed me to take it up as one of my two subsidiary subjects in Dhaka University. And I had two of the best teachers that the department could offer to guide me through the long winding intricacies of South Asian history and modern European history. Prof. Santosh Bhattacharjee was excitable as he delivered his lectures in a somewhat high-pitched voice. The man was encyclopedic. Prof. Giasuddin Ahmed was equally knowledgeable, but his voice was measured, sonorous, commanding. He was unforgettable in hammering into our heads a defining event in human history, the French Revolution. Oh, those being the days, they lectured in impeccable English, but reverted to the familiar Bengali outside of class. And they were equally adept at both. Prof. Munier Chowdhury was the father of a friend and basketball teammate at Notre Dame College as well as of his younger brother, who was my cameraman in a telefilm that I had directed and acted in and which was broadcast from 2001 to 2004 over India's Alpha (now Zee) Bangla TV; and was tragically killed in a recent road accident. Prof. Serajul Huq Khan was the father of another friend and neighbour across a wide field in those days of livable Dhaka. Prof. G.C. Dev I had heard of before taking admission in Dhaka University, Prof. Jyotirmoy Guhathakurta shortly after. How can I forget Prof. Dev, with his Einstein-like head of hair, not quite Einstein-like moustache, in dhoti and, during winter, a somewhat faded black coat encompassing his considerable bulk, slowly trudging along, the very picture of the proverbial absent-minded philosophy professor? None of the martyred intellectuals willingly sacrificed themselves. They were forced to embrace martyrdom for what they symbolized. They were sacrificed at the altar of a shared vision. That vision was that of a nation at one, striving for a sovereign independent homeland. Theirs was a vision of a nation equated with a nation-state. The nation! That, to reiterate, was the ideal of the martyred intellectuals! But we find ourselves increasingly a nation divided, against itself, along entrenched fault lines that, sadly, seem to be widening with each passing year, with no end in sight for the foreseeable future. As if to reinforce this conclusion, we find many of today's intellectuals as fiercely divided as any other group, along the same fault lines, and, in certain cases, even having contributed towards some of it. Know what? The intellectuals martyred forty years back could be proverbially turning in their graves, real or symbolic. And they would have every reason to do so. The writer is head, Media and Communication department, Independent University, Bangladesh. We still hope for justice Roquaiy Hasina Neely

Despite being a lecturer in the English department of Dhaka University, my father martyred intellectual S M A Rashidul Hasan had a deep love for and attachment towards Bengali culture and literature. From his behavior to attire, everything reflected Bengali tradition. Tagore literature and Tagore songs were his favourite. This is why I became a Tagore singer. It was his dream that his daughter would sing Tagore songs. In those times prior to the liberation, singing Tagore songs on TV and Radio was banned by the government. Even so, my father enrolled me at a music school so that I could learn to sing his favourite songs. He believed that nourishing Tagore literature and practicing Tagore songs are vital to keep Bengali culture alive. I have always seen that whatever he thought was good, he tried his best to abide by it and implement it in his life and surroundings. Hence, my musical education continued despite government obstructions. His vision got me where I am today. The ability to retain and practice our own cultural values is a great achievement of our independence. Today we are free to exercise our cultural rights as a nation. We are free to talk, write and sing in Bangla. A Tagore song is our national anthem. In the past 40 years our country has developed much in terms of culture and education. Bengali singers are famous all over the world. Bengali students and teachers could be found in the top universities of the world. We are moving towards becoming a technologically developed country as well. But with advancement of science and technology we sadly notice that our young generation, being heavily influenced by foreign culture, is slowly diverting from our own traditions. These subtle shifts in the young ones pose a great threat to our unique entity. Bengali culture itself is very rich and exquisite. We do not need adaptations of different cultures, instead it is our responsibility to make this culture known to our young generation the same way our parents upheld its beauty and depth to us. It is our duty to give a clear and precise idea about our nation's history to the young ones. Through proper guidance and enlightenment we Bengalis as a nation can hold our heads high before the whole world well without being jingoistic. Our nation was freed from our Pakistani oppressors with the hope of building a golden nation. Maybe we have achieved quite a lot in the 40 years but still I feel that we have not become the nation that my father had dreamed of. The people who had laid down their lives for our country did not envision a country as it is now and I believe the politicians are largely to blame for this. After the liberation Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman called in the widows of the martyred intellectuals to ask what they wanted from an independent Bangladesh. Everyone answered that they wanted justice brought to the murderers of their husbands. Sadly enough, even after 40 years their demand has not been met with. Murder of intellectuals was a planned event. National traitors known as Rajakar, Al-badar, and Al-shams joined forces with the Pakistani army and executed the massacre. With defeat banging on their door their last desperate act of crippling our nation was to kill our intellectuals who provided us with hopes and dreams of a new Bangladesh. What I still do not understand is how such a heinous act goes unpunished for four decades? Why is not justice being delivered? How long will the political leaders put it off for their own benefits? Is it not embarrassing enough to see that the ones who didn't want a `Bangladesh' in the first place somehow ended up being a minister of Bangladesh, riding in cars bearing the country's flag? The culprits are not unknown. So what is it that is keeping the authority from punishing them? I have lost my father, the person I held dearest to my heart, in the hands of the traitors of Bangladesh. My mother has struggled and sacrificed enough to raise her three children alone, without much help from the government. It is about time we saw justice being served. After 40 years I still dream of a nation my father had dreamt of. But in order to establish that country, the murderers of my father and other intellectuals must be brought to justice because I believe that even after 1000 years people of Bangladesh will not forgive the traitors. Massacre of the Bengali intellectuals in 1971 Rafiqul Islam

On the 25th March night of 1971 the Pakistan Armed Forces unleashed their 'Operation genocide' at the Dhaka University campus, EPR headquarters in Pilkhana and Rajarbag police headquarters simultaneously with full force. At that time I was a resident of the University quarters, Nilkhet, adjacent to Iqbal Hall (Zahurul Haq Hall) and witnessed the brutality of the Pakistan Army. At the outset Pak Army used heavy machinegun, mortar, rocket launcher and artillery fire on the residential quarters and halls of the Dhaka University particularly in Iqbal and Jagannat Hall areas. In the early hours of 26th March, heavily armed Pakistani troops entered the residential halls and quarters situated in and around Iqbal and Jagannat halls. Pakistani soldiers massacred the teachers, students and employees in their own quarters throughout the day and night of 26th March and set the rooms of the residential hall in blaze. On 26th March, they dragged the corpses to the ground of Iqbal and Jagannat Hall and buried them in mass graves. They forced the students and employees to carry the bodies of the killed students and teachers, dig mass-graves and throw them into the graves. Later on they shoot and kicked them into the mass-grave. The barbarity perpetuated by the Pakistan Army on 25th and 26th March 1971 in Dhaka University campus has no parallel in the history of our time. Between 25th and 27th March, 1971 the Pakistani solders brutally killed the following Dhaka University teachers inside their own house; Dr. G C Dev of philosophy, Prof Muniruzzaman of Statistics, Dr. Jotirmoy Guha Thakurta of English, Dr. Fazlur Rahman Khan of Soil Science, Prof. Sharafat Ali of Mathematics, Prof. Abdul Muktadir of Geology, Prof. A.R. Khadim of Physics, Prof. Anudaipayan Battacharja of Applied physics and Mr. Mohammad Sadeque, a teacher of the University Laboratory School. Among them Prof. Muniruzzaman, Dr. Fazlur Rahman and Dr. G C Dev were killed along with their family members. A large number of students and employees of the Iqbal, Jagannat and Rokeya Hall, Dhaka University teacher's club were also killed. Among them were Madhuda (the owner of Madhu's canteen) and his family. The inhabitants of the nearby slumps along the old railway track were gunned down mercilessly by Pakistan troops. The dead bodies from the slumps were heaped in front of the Nilkhet petrol pump and burnt to ashes. About a thousand unarmed E.P.R recruits in Pilkhana were slaughtered mercilessly. Only in Rajarbag police line the invading Pak Army faced stiff resistance and tanks were brought in. A large number of resisting police personnel were butchered. The entire Ramna and adjacent areas turned into burning inferno on 25th and 26th March, 1971. Besides Dhaka University campus, EPR and police headquarters, the invading Pakistan Army systematically destroyed all the slumps, bazars, fire brigade and police stations, newspaper offices, political parties' headquarters, residences of political leaders and the Shahid Minar in Dhaka city. Pakistan Army also launched a genocide campaign on the inhabitants of old Dhaka particularly in Shakhari Bazar, Tanti Bazar, Luxmi Bazar, Narinda, Moishandi etc. Kamalapur railway station and Sadarghat launch terminal also came under Pakistani campaign. Thus Dhaka witnessed the greatest exodus of the city dwellers in its history from 27th of March. By the end of March 1971, Dhaka became an empty and ghost city. During the nine months of siege Dhaka city became a battlefield between occupying Pakistan Army and the valiant guerilla forces of the Bangladesh Muktibahini. The guerrillas launched assaults on Hotel Intercontinental and D.I.T Bhaban, and also at Farmgate area and different electric sub-stations. On the other hand, the Bihari areas, particularly Mirpur and Mohammadpur, became a slaughter house for the Bengalis. Thousands of Bengali young men and professionals were rounded up and thrown into torture camps in Dhaka cantonment. Hundreds of Bengali girls were abducted and kept in Pakistani camps for sexual abuse with the help of local collaborators. During 1971, Pakistan Marshal Law authority raised several collaborating forces namely Peace Committee, Rajakar Bahini, Al-Shams and Al-Badar Bahini. Among the collaborators most ferocious was the secret Al-Badar Bahni whose duty was to trace the Bengali intellectuals, teachers, writers, scientists, doctors, journalists etc. and pick them up from their hiding places; then torture and kill them in a hideous process. Thousands of Bengali intellectuals lost their lives in 1971. Among the Pak Army and Al Badar victims, the most prominent were poet Meherunnessa, jouranlist Shahid Saber, singer Altaf Mahmud, journalist Sirajuddin Hossain, journalist and writer Shahiddulla Kaisar; journalists Syed Nazmul Haq, Nizamuddin Ahmed, ANM Golam Mustafa and Selina Parveen; scientists Abul Kalam Azad, Siddique Ahmad and Amin Uddin; physicians Dr. Fazle Rubbi and Dr. Alim Choudhury. Among the Dhaka University teachers the Al-Badar killers abducted Prof Munier Choudhury, Prof Mofazzal Haider Choudury, Prof. Anwar Pasha, Prof. Rashidul Hasan, Prof. Santosh Bhattacharja, Prof. Abul Khair and Prof. Giashuddin Ahmed; and Dr. Mortuja (physician), Dr. Faizul Mahi and Dr. Sirajul Haq Khan. These intellectuals were taken to Al Badar torture-camp situated in Mohammadpur Physical Training College. They first inflicted physical pains and then took them to Rayer Bazar slaughter house and Mirpur graveyard. In these two places the great minds of Bengal were brutally killed on 14th December just before the defeated Pakistan Army surrendered to the joint command of Bangladesh and Indian army. Thus the Pakistan Army and their local collaborators concluded their ethnic cleansing of the Bengali people in 1971. Though the Pakistan armed forces conceded defeat and surrendered, the Bangladeshi collaborators never surrendered. They are still active even after 40 years of independence. The writer is Professor Emeritus, University of Liberal Arts. My brother Munier Chowdhury Shamsher Chowdhury

During those dreadful days of Pakistani occupation, BBC became the most popular form of media for the entire nation. People relied more on the BBC than any other news service. About 48 hours before the surrender of the Pak army, my brother Munier Chowdhury and I were listening to the BBC, sitting on the outer balcony. When the commentator over the radio announced, “ The guns of India are rattling 28 kilometers from the capital Dhaka at a place called Daudkandi,” my brother embraced me and said, in a voice choked by emotion, “ Look, brother, our independence is irresistible.” Little did I know then that this was the last day of his life and that he would be kidnapped never to be seen again. 40 years have passed since the day he was taken away by some members of the infamous Al-Shams and Al-Badar, two of the collaborating wings brought up by the then occupation forces of Pakistan. They came around 11:30 a.m. on 14 December and began to fiercely hammer on the iron-grilled gate of the main entrance to the compound of our residence. I came out of the house and, on their repeated insistence, opened the gate. Three of them came in with their faces covered, wearing black shelwar and kameez, a popular dress worn by both men and women in West Pakistan. They asked for my brother who along with me was getting ready for a quick lunch since there was a lull in the bombing by Indian MIG 29. We already had our bath and were getting ready to join our mother at the dining table, where she was anxiously waiting for us. She hardly knew what was going on outside the house only 30 yards away from the room in which she was waiting with my sister-in law Lily Chowdhury, who was on the second floor of the house with her twelve year old son Mishuk Munier. Mishuk, very recently, met an untimely death in a gruesome road accident. In just about ten minutes, these hyenas took away my brother Munier Chowdhry right in front of my eyes. And there I stood, dumbfounded, for a very long time. I went to mother first, and as soon as I told her what had happened she broke down in tears. Mother passed away about 12 years ago, and every time I used to go near her, until the day she died, she used to say to me, “Son, why did Allah take his life instead of mine? My son was a gem of a boy; ever so clean of heart, kind and generous. Who would kill a man like him, who had never raised a finger against anyone?” She used to ask me the same question, over and over again, to which I had no answer. My sister- in- law always felt that had I been a little more alert, I could have found a way out for my brother to escape. I do not know the answer to that too, except for the fact that I have since that fateful day been living with that burden in my chest for 40 long years. Forty years have passed since that day; we neither found his dead body nor did we know how brutally he had met his death. For two of the longest days of my life, after the surrender of the Pak occupation forces, with the help of a Colonel of the Indian Army and two soldiers, I went through every nook and corner of the city and its outskirts trying to find my brother's body. Finally, after two days of failed search, on the evening of 18 December, my mother called me to her bedside and said, “Son, abandon the search, even if you find the body it must be in a mutilated condition in a ditch beyond recognition. I have lost one son and do not wish to lose another one. They say that some of those killers are still prowling around.” As for me, I no more have a howling pain but the deep scar lingers on. To be honest, the death of Munier Chowdhury has influenced my life in more ways than one. He was a giant of a man, in every sense of the term, and yet so humble, and extremely tolerant of others' views. He treated his students as members of his family. He was a visionary and a thinking man way ahead of his times. Like our father, he believed in the eternal power of education and education alone. Contrary to popular belief, he was a man who had an unflinching faith in his Creator. During the last days of his life from October 1971 till the day he was kidnapped, he routinely sat beside my mother close to her prayer mat with a book or a pen and a copy scribbling and reading at the same time. One of those days, a group of young men came to the house to escort him across the border into India. They were sent by his eldest son, who was then in India, getting ready to join the Liberation Forces. Mother, with tears in her eyes, tried to persuade him to go, but he stood his ground and refused to leave by saying, “Look, mother, how can you say this being a staunch Muslim and a God fearing individual. You know too well that each individual is destined to die wherever God wills.” In reference to this, I would also like to recall yet another shining aspect of Munier Chodhury's character. My father, even in his last days, used to go for his Juma prayers to the nearby Paribagh Masjid. My brother, each Friday, took him to the mosque, waited until the prayer was over and then brought him back to the house. He used to come to the house from his residence at Nilkhet to pick up my father. On arrival at the mosque, he used to park his car under the shade of a flame tree (Krishnachura) close to the mosque, take out a book from the glove compartment of the car and begin to read until the prayer was over. Imagine a man doing that religiously every Friday who never said prayers in all his life. Being asked, he told me that he believed more in living religion rather than practicing religion as a mere ritual. His religion consisted of serving humanity in all conceivable ways. He taught each one of us all about plain living and high thinking. Till the last days of his life, Munier Chowdhury was seen in the corridors of the University dressed in a set of clothing made of khaddar. He loved his country most dearly and was always thinking how to do something new and innovative. He was the inventor of a typewriter key board in Bangla, in collaboration with a German typewriter manufacturing outfit known as the Optima, which still bears his name. He was the pioneer of modern day theatre through his groundbreaking plays. Munier Chowdhury was a living legend. He was gentle, polite and a speaker of exceptional calibre. During his teaching career, students from other classes studying different subjects used to flock together to listen to his lectures. He treated his students like his family. I have never seen him being angry at anyone, no matter what. This is the image and memory of my brother I continue to cherish and will do so for as long as I live. The writer is a columnist and younger brother of Munier Chowdhury. |

© thedailystar.net, 2011. All Rights Reserved